| Age of Charlemagne | |

| Period | Early Middle Ages |

| Dates | 732-843 AD |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by Rise of Islam |

Followed by Viking Age |

| “ | I am the successor, not of Louis XVI, but of Charlemagne. | ” |

–Napoleon Bonaparte | ||

The Age of Charlemagne lasted from about 732 AD until 843 AD. It began with the rise of the Frankish Carolingian dynasty, which reached its peak with Charlemagne, a towering figure in European history. It then ended with the Treaty of Verdun, a settlement that was not long untroubled, but decisive in a very important way; it effectively founded the political distinction of France and Germany.

The first great empire of medieval Europe was the Frankish empire of Charlemagne; he was to become an almost legendary figure. Charlemagne was obviously still a traditional Frankish warrior-king; he conquered and his business was war. What was more novel was the seriousness with which he took his role as a Christian king. He patronised scholarship, education, art, and architecture, wanting to magnify the grandeur of his court by filling it with evidence of Christian learning. Territorially, Charlemagne was a great builder. He overthrew the Lombards of Italy, became their king, and their lands, too, passed into the Frankish hands. For thirty years, he hammered away at the pagan Saxons, and achieved their conversion by force. An invasion of Muslim Spain was less successful, though his establishment of the Spanish March, in time, secured the Pyrenees down the Catalonian coast to Barcelona. Returning to Germany, he next annexed the already-Christian Alemanni and Bavarians, and, perhaps as important, opened a route down the Danube to Byzantium. Thus he put together a realm of vast extent, unparalleled since the days of Rome. Historians have been arguing almost ever since about what Charlemagne’s coronation as emperor by the pope on Christmas Day 800, actually meant. There already was an emperor whom everybody acknowledged to be such: he lived in Constantinople. An element of papal gratitude was involved, clearly; Pope Leo III had just been saved for a second time by Charlemagne’s soldiers. Yet Charlemagne is reported to have said that he would not have entered St Peter’s had he known what the pope intended. He may have foreseen the irritation the coronation would cause at Constantinople. He must have known that to his own people, he was more comprehensible as a traditional Germanic warrior-king than as the successor of Roman emperors. He may have disliked the pope’s arrogation to himself of the authority to bestow the imperial crown. In fact, Charlemagne thought in traditional Frankish terms of his legacy. He made plans to divide his empire, and only the accident of one surviving son ensured that the territory passed undivided to the youngest, Louis the Pious. But partition was only delayed by this. A series of civil wars finally culminated in partition between Charlemagne’s three grandsons, the Treaty of Verdun of 843, which had great consequences. It established an eastern Frankish land that we can call Germany, though nobody did at the time; and a western one which eventually became France. Between them lay a third unit with much less linguistic, ethnic, and geographical unity, that was not long untroubled. Much future Franco-German history was going to be about the way in which these lands could be divided between neighbours bound to covet.

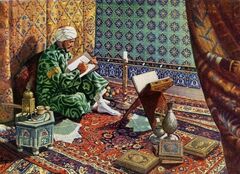

For all his achievement, Charlemagne's empire was a primitive thing when compared with the Islamic caliphate. In 750, the Umayyad dynasty was overthrown by a new house of Meccan origin, the Abbasids, who would rule the Arab world for nearly two centuries as a real power (and even longer as a puppet regime); the first century the most glorious. The capital was moved to the new city of Baghdad, a change had many implications. It suggests a new eastward focus, and, when a new threat arose on the caliphate's western edge, the Abbasids did not try very hard to solve it; and Spain became the first Muslim kingdom to be entirely independent of the caliphate. Roman influences were weakened; a new weight was given to the heritage of Persia, which became culturally and politically very important. There was a change in the ruling caste, too, and one sufficiently important to lead some historians to call it a "revolution". They were from this time Arabs only in the sense of being Arabic-speaking, they were no longer Arabian; the élites which governed the Abbasid empire came from many peoples right across the Middle East. They were almost always Muslim, but often converts or children of convert families. The cosmopolitanism of Baghdad reflected the new cultural atmosphere. A huge city, rivalling Constantinople, with perhaps a half-million inhabitants. Of Abbasid prosperity at its height there can be no doubt. It rested not only on its vast territory where agriculture was untroubled under the Arab peace, but also upon the favourable conditions it created for trade. A wider range of commodities circulated over a larger area then ever before. The luxury and delight of Baghdad under Harun al-Rashid, the most famous of the Abbasid caliphs, has been impressed on the western imagination by the most famous works of Arabic literature; One Thousand and One Nights. Al-Rashid's reign is remembered as the golden age of Islam. He inaugurated the House of Wisdom, a world centre of learning, which saw scholars from all over the Muslim world flock to Baghdad. One aspect of the flourishing of Arab scholarship was a great age of translation, that made available to Arab readers all the classic works of antiquity. This was, in time, of huge importance to Western Europe. The transmission function of Arabic culture, however, must not obscure its originality. Although Arab geography and history were both very impressive, its greatest triumphs were in science, philosophy, medicine, and mathematics. Nevertheless, with the death of al-Rashid, the zenith of the caliphate was lost; different regions of the empire started to break away in the form of separate emirates.

History[]

Frankish Carolingian Age[]

Pippin the Short was a historically important king. He was by far the greatest European ruler of his time; he was the first Carolingian to become king; he first crystallised the Carolingian alliance with the papacy; he was the first Frankish king to be crowned by a pope; he not only contained the Spanish Muslims as his father had, but drove them completely out of what is now France; he supported St. Boniface in reforming the Frankish church and evangelizing the Germanic tribes. It was, however, his misfortune to be overshadowed by a famous father, and a still more famous son.

After turning back the Arab armies at Tours, Charles Martel (718-741) was de facto ruler of the Frankish realm until his death almost a decade later. When the do-nothing Merovingian king, Theuderic IV, died in 737, he did not bother to appoint another; though he did not himself assume royal dignity. He was princeps of the Franks, mayor of the palaces, had more power than anyone else in the western landscape. So when Pope Gregory III fell out with the Lombard king Liutprand in 738, he appealed to Charles Martel for help; "For by doing this you will attain lasting fame on earth and eternal life in heaven". Gregory III is credited with first articulating what would motivate later crusaders: the salvation offered to those who fought in the name of the church. Unfortunately, it did him no good. Charles was unconvinced by the pope's redemptive rhetoric. He was loath to fight his one-time Lombard ally and ignored the plea. The stand-off in Italy was finally resolved by the death of everyone involved; Charles and Pope Gregory died in 741, and Liutprand in 744 after an astoundingly long thirty-two reign. It had been a relatively minor quarrel, but Gregory’s appeal to Charles Martel had revealed a shift in the political landscape. In a world where the protection of the Byzantine emperor had been whisked away, the bishops of Rome were forced to seek protection from whatever power might be willing. In 751, even the nominal claim of the emperor to rule in Italy was destroyed. The Lombards finally captured Ravenna under their aggressive new king Aistulf, and killed the last Byzantine exarch,. A few patches of Italian territory remained loyal to Constantinople (notably, the city of Venice), but now there was no imperial government on the peninsula. Byzantine cities had to govern themselves, and the popes, too, were on their own. After his death, Charles Martel’s two sons inherited his power; Carloman as mayor in Austrasia, and Pippin the Short (741-768) in Neustria. The brothers decided to put a figurehead king on the Frankish throne, which had been empty for seven years. This was Childeric III, though he played no role in government. Neither, after a few years, did Carloman. In 747, he was consecrated as a monk, and withdrew to Monte Cassino, the monastery established by St. Benedict himself. This left Pippin the Short as sole mayor, and in 751 he decided to remove Childeric III and claim the throne himself. However, a lingering regard for royal blood caused him to search for a greater sanction than himself for his usurpation. And so he now addressed to Pope Zachary a suggestive question: "Is it better for the man who possesses the royal power to be called king, than the one who remained without royal power?" Zachary, hard pressed by the Lombard king, was willing to trade the church’s approval for Frankish protection. Childeric III was thus tonsured and sent to a monastery, where the last of the Merovingians died five years later. Pippin was crowned the first king of the Carolingian dynasty in the city of Soissons, in a brand-new sacred ceremony that involved holy anointing oil in the manner of an Old Testament prophet or Israelite king. Zachary died in 752, but his successor, Pope Stephen II, was careful to put himself in a position to reap the benefits of that coronation. In 754, he travelled north into the lands of the Franks and re-anointed Pippin in an even more elaborate ceremony. He had tied the Frankish king’s power to papal authority, and King Pippin responded by marching across the Alps down into Italy, driving Aistulf out of the papal lands, and the lands once governed by the Byzantine exarch. And he gave all of them to the pope; the so-called Donation of Pepin, whereby the Papal State officially began. The Lombard army was badly defeated, and King Aistulf was forced to recognize Pippin as his overlord. Then, when Aistulf died in a hunting accident, Pippin chose a Lombard nobleman named Desiderius to be the next Lombard king in Italy. In half a decade, he had become not only king of the Franks, but the de facto ruler of Italy as well. Pope Stephen II didn’t do badly either. He now ruled over a much expanded Papal State. To justify his possession of this lands, he presented Pippin with an imperial decree that (he claimed) had been written by Constantine. In it, the emperor explained that a fourth-century pope had healed him of a secret case of leprosy, and, in gratitude, he bestowed on the papal seat, "power, and dignity of glory, vigour, and imperial honour," and "supremacy also over the four principal sees [Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Constantinople], as also over all the churches of God in the whole earth". This document, known as the Donation of Constantine, had been forged by some talented cleric, and the ink was barely dry. Pippin, who was no fool, no doubted knew this. But the popes had given him the authority he craved, and, in return, he was willing to award them power over Rome, Ravenna, and the surrounding lands.

Charlemagne towered over his contemporaries both figuratively and literally; he was 6 ft 5 in. He was more than a traditional Frankish warrior-king who led his people to war and conquered; though he often did that. What was more striking was the seriousness with which he took his Christian role and his promotion of learning and art; he wanted to magnify his kingship by filling his court with evidence of Christian culture.

While Pepin the Short was the first of the Carolingian kings, it was his son Charles, better known as Charlemagne (768-814), who brought the dynasty to historical immortality. He ruled, in the first years of his reign, alongside his brother Carloman. The siblings divided the administration of the empire, although not along the old Neustrian-Austrasian lines; instead, Charles ruled the northern lands, and Carloman the southern. Two years after his accession, Charles married the daughter of Desiderius, the Lombard king who his father had appointed. Less than a year later, he repudiated his wife (“Nobody knows why,” writes Einhard), and, in her place, married an Alemanni princess named Hildegard. This gave him useful connections to the east, where the sometimes-troublesome Alemanni people lived. Naturally, this infuriated the Lombard king, who proposed to Carloman that they join together to destroy Charles. The kingdom was, however, saved from civil war by Carloman’s death in 771; the death, unexpected and convenient though it was, was set down to natural causes. Charles now ruled as sole king of all of the Frankish lands. Almost at once, he began to enlarge them through conquest. In 772, he set off north-east to fight against the Saxons, just east the Upper Rhine river. The land around the Rhine was rich, and the Saxon tribes were not well united. They were divided into three main subgroups; the central Saxons on the Weser river, the Eastphalians on the Elbe, and the Westphalians closer to the coast. Charles pushed into the Saxon lands, and beat his way through the disorganized resistance to their most sacred shrine: the Irminsul, a great wooden pillar representing the sacred tree that supported the vault of the heavens (similar to the Nordic tree Yggdrasil). He ordered the shrine destroyed, intending to show the Saxons that, as a Christian king, he dominated both the Saxons and their gods. The destruction of the Irminsul would haunt him for decades. The Saxons were not politically united enough to mount a strong defence, but they held a single set of religious beliefs. The destruction of the Irminsul would remain long in their memories. Leaving the Saxons temporarily subdued, Charles returned home and prepared to march south-east. In 773, he crossed the Alps into Italy, set on punishing Desiderius for his plotting. He pushed through strong Lombards resistance, and captured their capital city at Pavia, after a protracted siege. The last Lombard king was imprisoned in a monastery, where he was never seen or heard from again. The result was a major extension of his empire, and a new title for himself, King of the Lombards; he claimed the famous Iron Crown of the Lombards, which tradition held was beaten from a nail of the True Cross. Charles now controlled the northern part of Italy, the old Lombard kingdom; acted as the protector of the Papal State in the middle of the peninsula; and as overlord of two Lombard duchies (Spoleto and Benevento) in southern Italy. It was the first of the great victories that would earn him the name Charlemagne (from the French Charles-le-magne or "Charles the Great").

Charlemagne next set his sights on south-west, hoping to take advantage of Muslim difficulties. Al-Andalus had now become entirely independent from the caliphate. After the Abbasids seized power in 750, a fugitive Umayyad prince named Abd ar-Rahman had made his way, over six long years, across North Africa to the last loyal Umayyad province left in the Muslim world. There, he proclaimed himself emir (prince, not king) in 756; the Emirate of Córdoba (756–929). Abd al-Rahman tended to place his own family members in high offices across the land, which did not sit well with all of the Muslims. In 778, a group of dissidents in the north-eastern part of al-Andalus, led by Sulayman al-Arabi, invited Charlemagne to help them get rid of Umayyad rule. He promised him that the city of Zaragoza, well inside the border, would open its gates to him, so that he could use it as his base of operations. This must have seemed like an excellent idea, but it ended in disaster. Charlemagne marched to Zaragoza with his men, visions of conquering al-Andalus in his head. When he arrived at its walls, however, Sulayman al-Arabi changed his mind and refused to let him in. Without a walled city to protect him, Charlemagne was forced to withdraw back through the Pyrenees. He was furious, and, on the way home, he sacked and destroyed the town of Pamplona as he passed it. This, like his destruction of the Irminsul, was a mistake. Pamplona was not controlled by the emir of Cordoba; it was Basque settlement, a tribe that had been in Hispania before the Romans arrived. They had survived in their mountainous land through the Roman occupation, the Visigoth takeover, and the arrival of the Arabs. They were tough, resourceful, and experienced in the mountains. At the Pass of Roncesvalles, the Basques took their vengeance, attacking the end of Frankish column, and wiping out the rear guard to the last man, before disappearing into the rough terrain. The ambush was disproportionately devastating to Charlemagne, because a number of his personal friends had been in the rear. Among them was a man named Roland, warden of the "Breton March"; the militarized borderland with Brittany. This minor defeat became the most famous moment in the whole Charlemagne legend, inspiring the first major work of French literature, the eleventh-century Song of Roland. While Charlemagne himself would never pushed his way past the Pyrenees again, he did establish the Spanish March, which over the next decade would push the frontier as far south as Barcelona. Charlemagne had grown not just in power, but in his role as Christian king as well. The days of the mayor of the palace, reluctant to lay full hold of royal power, were long past. He had gathered a royal circle of scholars and clerics at Aachen (his newly chosen capital city), who were filling in the gaps from his early education; he had received from his father much more military training than book-learning (and he had never learned to write). They not only discussed with him the finer points of theology, philosophy, and grammar, but most of the surviving classical texts in Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars. Under the guidance of his personal tutor Alcuin, an Anglo-Saxon churchman, Charlemagne developed a stronger and stronger sense of mission. His conquests were, in his own eyes, forceful evangelism; bringing the Gospel to stubborn unbelievers, who needed to be saved from their own unwillingness to hear. He was forced to return and reconquer the Saxon lands in 776, and again in 779, where they still would not submit to his rule or repudiate their religion. But their leader Widukind escaped each time to Denmark, his wife's home. The Saxon toll on his army so angered him that, in 782, he ordered the execution of forty-five hundred Saxon prisoners in an atrocity known as the Massacre of Verden. That triggered three years of renewed bloody warfare. The war ended with Widukind's surrender and acceptance of Christian baptism. Afterwards, Charlemagne promulgated a draconian decree that any Saxon who remained unbaptized, or did not observe Lent properly, or indulged himself in the old Saxon worship, would be put to death. Alcuin objected, telling the king, “do not force them by public compulsion until faith has thoroughly grown in their hearts". Charlemagne agreed and abated a little. In his numerous subsequent campaigns, he annexed the Germanic Alemanni lands, and the Bavaria, a territory that had coalesced out of the remnants of several tribes; both of which had already been under Frankish suzerainty and semi-Christian. The remaining power confronting the Franks in the east were the nomadic Avars. Since the Siege to Constantinople of 626, the vast Avar realm had fallen apart, but an isolated remnant survived in what is now Hungary. In 790, Charlemagne marched down the Danube and ravaged Avar territory, but then had to halt his campaign to deal with a Saxon revolt. Instead of taking advantage of the reprieve, the Avars fought among themselves, and the conflict eventually broke into open civil war, in which the leaders of both factions were killed. Soon, a third Avar leader lost the will to fight, and travelled to Aachen to offer his subjection to Charlemagne, who accepted, but then attacked anyway in 795. The Ring, the Avars' capital fortress, was taken easily, and great hoards of booty carried off to Aachen.

Historians have long debated whether the imperial coronation had been jointly planned by Pope Leo and Charlemagne, or whether Charlemagne was taken completely by surprise. But that debate obscured the more significant question of why the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne accepted it. Everybody already acknowledged an emperor, the one who lived in Constantinople: were there now to be two emperors, as in later Roman times? An element of papal gratitude was certainly involved. Yet Charlemagne is reported to have said that he would not have entered St Peter's had he known what the pope intended to do. He may have disliked the pope's arrogation to himself of the right to appoint the emperor; "establishing the imperial crown as his own personal gift but simultaneously granting himself implicit superiority over the emperor whom he had created".

Charlemagne could easily think of himself, at this point, as equal in stature to the emperor at Constantinople. He had raised the kingdom of the Franks to a single political unit of vast extent, unparalleled since the days of imperial Rome. He was creating a dynasty; he had crowned his third son Pippin as king of Italy, his fourth son Louis as king of the Frankish territory Aquitaine, and he ruled over them as an emperor rules over vassal kings; his second son, Charles the Younger, was being groomed to inherit the job of king of the Franks. And he was receiving constant proofs of his own high status among the kingdoms of the west. In 798, King Alfonso II, the ruler of the Christian kingdom of Asturias in the mountainous north of Hispania, sent him a formal embassy. Since its beginnings in 718, the kingdom had grown strong enough to pillage Moorish land along the coast all the way down to the city of Lisbon. Alfonso wanted recognition from Charlemagne, the greatest Christian king of the west, for the legitimacy of his own throne. Charlemagne never doubted that such an assurance was in his power to give. The following year, he was asked to carry out an even more imperial duty. Pope Leo III (795-816) had run into trouble. He was not terribly popular in Rome, either because he wasn't an aristocrat, or because he was immoral and dishonest; no proof for the latter accusations survives, so it is difficult to trace the roots of the enmity. For whatever reason, the hostility swelled until, in 799, a band of his enemies physically attacked him in the streets of Rome; their stated intention was to cut out his eyes and tongue, thus making him incapable of office. So Leo fled. In normal circumstances, the pope would have made his way to the emperor at Constantinople; but the imperial throne was, at that time, occupied by the Empress Irene. The fact that Irene was a usurper who had gouged out her own son's eyes was, in the minds of both Leo and Charlemagne, almost immaterial; it was enough that she was a woman. As far as the West was concerned, the imperial throne was vacant. Pope Leo made his way to visit Charlemagne at Paderborn. At Leo’s consecration as pope, Charlemagne had promised to defend the church; he had not envisioned defending it at Rome with arms, which was what Leo was asking; and the situation was further complicated by the fact that several Frankish officials believed that the charges were true. But whether or not Leo was guilty was almost a side issue. If the pope spoke for God, his position had to be unassailable. Charlemagne, swayed by his advisor Alcuin, marched “in full martial array” to Rome, in November 800, and held a synod. Leo put his hand on the copy of the Gospels in St. Peter’s Cathedral and swore that he was guiltless of any wrongdoing. With Charlemagne and his soldiers standing by, his word was accepted. Charlemagne lingered in the city until Christmas. As he rose from his knees at the conclusion of the Christmas Mass, Pope Leo came forward and laid the imperial crown upon his head. The whole congregation, which had been coached, cheered; "Most pious Augustus, crowned by God, the great and peace-giving Emperor," ran the chant. He had been crowned imperator et augustus, two titles that belonged to the Roman emperor; titles that, in the eyes of the Byzantine court, had long ago been transferred to Constantinople. Charlemagne’s biographer Einhard claims that he knew nothing about the plan to crown him. But the coronation was simply a formal recognition of an authority that Charlemagne had been claiming for some time: the authority to stand as the protector of faith, guarantor of civilization, and highest civil power in the Christian world. Charlemagne must have expected his crowning to cause irritation at Constantinople, and, indeed, relations with Byzantium were soon troubled; though the new title was tentatively recognized a few years later, in exchange for recognising Byzantine sovereignty over still loyal Venice and Sicily. With another great state, the Abbasid caliphate, Charlemagne had somewhat formal but not unfriendly relations. The caliph Harun al-Rashid is said to have gifted him a water-driven clock, a chess set, and, most strikingly, an elephant; we learn this from Frankish sources, for they do not seem to have struck the Arab chroniclers as worth mention. Charlemagne liked the idea of a war elephant, and took it with him, in 808, when he campaigned against the Danes to the north; which undoubtedly startled them. The Umayyads of al-Andalus were different; they were near enough to be a threat, and to protect the faith from "pagans" was a part of Christian kingship, so Charlemagne did not court them.

The Palatine Chapel in Aachen, where Charlemagne was buried. In 936 Otto the Great, the first Holy Roman Emperor, took advantage of the chapel's association with Charlemagne and held his coronation there; which continued until 1531. Today, the chapel forms the central part of Aachen Cathedral.

When his reign began, Charlemagne's court was still itinerant, eating its way from estate to estate throughout the year. At his death, he left a real capital city at Aachen, which he strove to beautify. Five years after the coronation in Rome, Leo III was again with Charlemagne at a religious ceremony. But this time he was consecrating a small but richly decorated octagonal chapel in Aachen, which Charlemagne had consciously modelled on another famous imperial church; Justinian's San Vitale in Ravenna. Charlemagne made plans to divide his lands in the traditional Frankish manner, but he was unfortunate; though he had four wives, six additional consorts, and thirteen children, two of his three legitimate sons died before him, so that the inheritance passed undivided to the youngest, Louis the Pious. In 813, Charlemagne called the court noblemen together and, in their presence, crowned Louis as co-king and co-emperor; the old Germanic tradition of electing a king meant that, although he had no intention of giving the nobles a voice in the succession, they needed to be included in the ritual. The following year, Charlemagne fell ill with a fever after bathing in his beloved warm springs at Aachen; he died one week later. Writing in the 840s, his grandson Nithard writes, “Above all, I believe he will be admired for the tempered severity with which he subdued the fierce and iron hearts of Franks and barbarians. Not even Roman might had been able to tame these people, but they dared to do nothing in Charles’ empire except what was in harmony with the public welfare”. Modern historians have made apparent the exaggeration in that statement by calling attention to the inadequacies of Charlemagne’s political apparatus. A Frankish court was a primitive thing in comparison with Byzantium; and possibly even in comparison with some early barbarian kingdoms like Theodoric's one in Italy. His power was personal and hardly institutionalized. His noblemen were bound to him by especially solemn oaths, but even they began to give trouble as he grew older; his frequent re-issuing of capitularies (royal commands) was a sure sign that his wishes were often ignored. Such critical attention, however, cannot efface the fact that his feats as a ruler, both real and imagined, served as a standard to many generations of European rulers. His restoration of the empire provided the ideological foundation for a politically unified Europe, an idea that has inspired Europeans ever since; sometimes with unhappy consequences. His definition of the role of the secular authority in directing religious life laid the basis for the tension-filled interaction between Church and State that played such a crucial role in shaping western European history. His cultural renaissance provided the basic tools - schools, textbooks, libraries, and teaching curricula - upon which later cultural revivals would be based. Such accomplishments certainly justify the superlatives by which he has been known: Charlemagne (“Charles the Great”) and Pater Europae (“father of Europe”).

Frankish Carolingian Heritage[]

All the Carolingian kings tended to have nicknames, most of which were contemporary or nearly so, because the royal names were so few in number. Charlemagne's son got luckier than most to be called Louis “the Pious”. After him came Charles the Bald, Louis the Stammerer, Charles the Fat, Louis the Sluggard, and so on.

Only chance ensured that the empire passed undivided to Louis the Pious (814–840), the last surviving son of Charlemagne. With it went the imperial title (which Charlemagne bestowed without papal approval), and the alliance with the papacy. During his father's reign, Louis had gained much valuable experience as ruler of Aquitaine. Aquitaine was no picnic; incorporated into the Carolingian regime by force, its nobles needed watching, while the region abutted the Spanish March, which had become even more dangerous after Charlemagne’s abortive campaign of 778. It had been him who conquered Barcelona for his father in 801. Louis had very sophisticated ideas about imperial rule; perhaps even more sophisticated than those of Charemagne, because Louis was better educated. But he was less pragmatic, less realistic, and lacked Charlemagne's instinctive charisma of leadership. Louis' principal preoccupation was how to maintain the unity of the empire, while at the same time providing positions for all of his sons. In 817, he crafted a blueprint for this empire, the Ordinatio imperii. His eldest son Lothair was to be sole heir and co-emperor; his younger sons, Pippin and Louis "the German", were assigned subordinate roles as kings of Aquitaine and Bavaria, respectively. Louis may have thought of his sons as his subjects and his empire as a single realm, but his sons viewed their share of the kingdom as peculiarly their own. In 829, the two different points of view clashed and threw the empire into civil war. The immediate cause of the war was the remarriage of Louis, and the birth of a fourth son, Charles "the Bald". Louis' attempt to change the Ordinatio imperii to provide a kingdom for little Charles met stiff resistance from his older sons and caused much civil strife. Notably, he faced a revolt in 830, and a second, more serious revolt in 832-833. In June 833, Louis met Lothair at the so-called “Field of Lies” near Colmar in Alsace, ostensibly to settle their differences. Instead, the emperor found himself facing a coalition of his three eldest sons, and Pope Gregory IV; whom Lothair had confirmed in office without his father's support. In a humiliating ceremony, he acknowledged his sin, removed his imperial regalia, and accepted permanent penance in a monastery; and Lothair claimed the throne. This mistreatment of a father by his sons, however, led to another round of increasing vicious conflict, in which support swung back to Louis, who orchestrated his return to the throne the next year. Lothar lived in disgrace for the rest of his father's life. The next revolt occurred a mere four years later, in 638. When Pippin died unexpectedly in Aquitaine, Louis announced that Aquitaine would now go to Charles the Bald. But the people of Aquitaine rebelled and crowned a king of their own: Pippin’s own son, Pippin II. The emperor quickly subjugated Aquitaine, and his reign ended on a high note, with order largely restored to the empire,

Upon Louis' death in 840, Lothair claimed overlordship over the entirety of the empire, in an attempt to reclaim the power he had at the beginning of his father's reign. He was supported by his nephew, Pippin II, who still sought to claim Aquitaine. But his brothers, Charles the Bald and Louis the German, refused to acknowledge Lothair's suzerainty. Civil war began again, and went on for another three years. While war killed off Frankish warriors, aggravated by opportunistic nobles, seaborne raiders from the north began to terrorize the North Sea and Atlantic coasts. After several battles, including a particularly bloody one at Fontenoy, the brothers finally decided that they’d better make peace before the entire country went up in flames. They met together in 843 and agreed to a document with great consequences, the Treaty of Verdun. Lothair received Middle Francia, the core Frankish lands centred on the Rhine valley, and containing Charlemagne's capital at Aachen; which later became the Low Countries, Alsace-Lorraine (then called Lotharingia), Burgundy, Province, and Italy. Louis the German received East Francia, all the German speaking lands to the east of the Rhine. Finally, Charles the Bald received West Francia, a tract of territory corresponding very roughly to modern France; his nephew Pippin II did receive Aquitaine, but only as Charles' vassal. This settlement was not long untroubled, but it was decisive in a broad and important way; it effectively founded the political distinction of France and Germany, whose roots lie respectively in the west and east Francia. Middle Francia had much less linguistic, ethnic, geographical and economic unity than either of these; and suffered as a result of Lothair's death in 855. It was, in subsequent centuries, one of the great fault lines of Europe. Much future Franco-German history was going to be about the way in which these Rhineland provinces could be divided between neighbours bound to covet them. But for now, Charles the Bald had the most difficult task. He soon faced a threat that was harder to deal with than his land-hungry brothers; viking longships found the broad Seine and Loire rivers an ideal path into his kingdom.

No royal house could guarantee a continuous flow of able kings, nor could they forever buy loyalty from their supporters by giving away land. Charlemagne's administrative system had worked exceedingly well while the empire was expanding. As long as the counts had the opportunity to conquer and plunder, they were happy to move around at the emperors will. Once the empire was at peace, their motivations and powers changed. Weak kings found it easier to leave the old count in place, and, when he died, chose a competent and semi-loyal member of his family to replace him.

No royal house could guarantee a continuous flow of able kings, nor could they forever buy loyalty from their supporters by giving away lands. Gradually, and like their Merovingian predecessors, the Carolingians declined in power.

They ruled in Germany until 911 and held the throne of France with interruptions until 987. The signs of break-up multiplied, dukes turned from appointed nobles into hereditary rulers of their territories, kings increasingly had to deal with regional rebellions, and people began to dwell on the great days of Charlemagne, a significant symptom of decay. This process was accelerated by their inability to resist the new foreign threats; the Vikings in the north, nomadic Magyars in the east, and Muslim raiders in the south. Because the sluggish royal armies were unable to provide effective defense against their hit-and-run tactics, military command, and the political and economic power necessary to support it, naturally devolved to local leaders. The reality everywhere was the fragmented politics that later historians called the Feudal System, though its nature varied from region to region. It was a widespread, but not universal, phenomenon. At its heart were the fief-lords, an aristocracy based on skill in battle and a shared commitment to Christianity; at once power-hungry and idealistic. Since the earliest post-Roman times, kings had granted them land and fiscal privileges, in return for loyalty guaranteed by especially solemn oaths and services, primarily of a military nature. At first, land grants had been temporary, surrendered at death, but by the 10th-century they had almost always become hereditary. Such lord and vassal relationships had old roots in Germanic custom as the warrior companions of the barbarian chief. In the 7th-century, the Carolingian Mayors had cultivated such relationships of mutual dependence with other lesser noble in order to usurp the power and then the throne of the late Merovingians. But they now came to characterised the whole socio-political structure. Vassals then bred vassals and one lord’s man was another man’s lord, in a chain of chain of obligation and personal service stretching in theory from the king down to the lowly knight and beyond. Knights were granted their own portions of the land, with an appropriate number of peasants to underwrite the expenses of military life; records suggest that the work of twenty to thirty peasant families was required to support one knight. With the weakening of royal authority, determined feudal lords, and indeed high clergy, were able to steadily impose the status of serfdom on formerly free peasants; the Manorial System. A freeman became a serf usually through force or necessity. Sometimes great physical and legal force intimidated freeholders into dependency. Often a few years of crop failure, a war, a Viking raid, or brigandage might force a person into striking a bargain with the lord-of-the-manor. As with slaves, serfs could be bought or sold with some limitations: they generally could be sold only together with land. In return for protection, justice, and land for their subsistence, they were obliged to work the lord's own fields, as well as in his mines, forests, and to maintain roads. The manor formed the basic unit of feudal society, and the lord and the serfs were bound legally.

There was much room for complexity and ambiguity in the interlocking Feudal and Manorial Feudal System: a man may have obligations to more than one lord with conflicting demands; a king might have less control over his own vassals than they over theirs; a lord might have a monastery as a vassal; or a king could be another king’s vassal in respect of some of his lands. Moreover, there were always some freeholders who owed service to no man for their lands, and much of Italy, Spain, and southern France did not work this way. For centuries, great accumulations of power and landed-wealth passed between a few favoured players as if in a vast board game. Bishops of cities and abbots of monasteries had their place in the feudal nobility, for they were great landlords too and mostly recruited from the noble families. Indeed bishops could often be found on the battlefield well into the 12th-century, fighting it out with the best. The papacy in Rome had more feudal vassals than any secular ruler in Europe by the late-12th-century. The second phase in the development of feudalism was the growing use of fighting in armour on horseback. Arab sources make cleat that at the Battle of Tours (732), the Frankish army consisted almost entirely of heavy infantry, fighting in a shield-wall with perhaps some cavalry on the wings. However, during Charlemagne's wide-ranging campaigns of conquest, more and more warriors took to horse; perhaps influenced by the Muslim way of fighting, or in response to hit-and-run tactics of Viking and Magyar raiders. At some point in the early-8th-century the stirrup had reached Europe, acquired either from the Muslims or Turkic Avars. With this, the medieval knight was ready to take the field. A mounted knight, protected first by chain-mail and then by plate-mail in the 13th-century, would drive home his lethal lance with the full forward impetus of his powerful horse. Europe was blessed with the destrier, a breed of exceptionally heavy horses which no longer exists today except as ancestors of the carthorse. Heavy cavalry further reinforced the social status of the feudal nobility, because this method of warfare was a tough and demanding, taking years of arduous training, as well as a great deal of money, not least for the armour, weaponry, and above all the horses. Relatively few warriors could afford to sustain themselves. With a knight's face concealed in armour, devices on helmet and shield were essential to identify friend from foe, and thus the "Coat of Arms" was born as a glorious way of advertising one's lineage; a distinguishing mark of European aristocracies. Knights and the ideals of chivalry would feature large in medieval literary romance, and still conjures up images of aristocratic heroes devoted to their ladies. But the reality was quite different. For the most part, these were rough brutes for whom violence was simply an accepted part of life; in any other part of the world, they would probably be called them warlords. The mounted knight would hold sway in the European battlefield until new weapons in the 14th-century, such as the pike and the longbow, restored some measure of advantage to the humble infantry. This was also the beginning of the great age of castle building, as lords entrenched their power in stone. Or more accurately they "entrenched their power in wood", for 10th-century castles were often surprisingly flimsy affairs called motte-and-bailey castles; a wooden keep situated on a raised earthwork called a motte, accompanied by an enclosed courtyard or bailey surrounded by a protective ditch, sometimes filled with water. It was only during the 12th-century that magnificently impressive stone examples become more common in Europe, influenced no doubt by exposure to Byzantine architecture seen by the Crusaders on their way east. Muslim Spain was clearly influential too; stone was the primary building material for Christian castles in Spain by the 11th-century, when timber still dominated in northern Europe

Feudalism was an exploitative and violent social system that legitimised rampant inequality. Even in normal circumstances the lord of the manor may terrorise his peasants into submission. In troubled times, peasants were less likely to assert themselves, for they needed the protection of his knights from marauding enemies. Whenever feudal relationships broke-down, disputes were invariably resolved through naked force. Another excellent excuse for warfare was a dynastic claim to a territory, as generations of carefully arranged marriages and material gains resulted in an immensely complex web of relationships. Feudalism nevertheless brought a modicum of local order and security when far-off kings or senior lords could not, and so prevented a total collapse of society. A lord was reasonably likely to care for his farms and his villages, since they provided him with sustenance; a cooperative labour-force was more productive than a resentful one. Feudalism would gradually decline in the Late Middle Ages, as the military power shifted from noble fighting-men to professional armies, and man-power shortages in the wake of the Black Death loosened the aristocratic hold on the peasantry. Feudal customs and rights nevertheless remained enshrined in the law of many kingdoms, until finally abolished during the turmultuous period between the French Revolution of 1789, and the Emancipation of the Russian Serfs in 1861.

Byzantines and the Iconoclasm Controversy[]

Idolatry is prohibited by many verses in the Old Testament; "Ye shall make you no idols nor graven image", Leviticus 26:1. But there is no clear definition. Is the use of religious imagery in worship idolatry? Judaism had historically used various images in connection with their worship, but later religious reform prohibited them. Islam is famously strict on the avoidance of images of living forms. Unlike them, Christianity has never really made up its mind. and the use of religious images has often been a contentious issue in Christian history. In the 16th century, Calvinists removed statues and sacred art from churches during the Iconoclastic Fury, and that influenced the Presbyterian and Anglican traditions. Today, religious imagery is most identified with the Catholic and Lutheran traditions.

After the great siege of Constantinople in 717–718, the Byzantine Empire no longer had to operate in crisis mode, and that was realised quite quickly. Leo III (717-741), the last of a revolving door of emperors raised by the army, was able to establish a solid power structure on the basis of his victory; which was inherited and carried forward by his descendants, the Isaurian Dynasty (717–802). Leo rebuilt the aqueduct system; secured the frontiers by settling captive peoples (mostly Slavs and Arabs) in the depopulated districts; and went on the offensive for the first time in a century, notably winning a battle against the Arabs at Nicaea in 726. This was the context, a moderately optimistic one, for the greatest of all the Byzantine ecclesiastical disputes, the Iconoclastic Controversy. Constantinople was home to scores of icons; paintings of saints, of the Virgin Mary, or of Christ himself. An icon was more than a symbol and less than an idol: an icon was a window into the divine, a threshold at which a worshipper could stand and come that much closer to the sacred. Christians had been using icons as an aid to worship for centuries. But a counter-thread of unease with these images had been stitched into Christianity from its beginnings. In the second and third-century, Christians had been distinguished from followers of the old Roman religion, in part, because they refused to worship images, for the use of icons veered perilously close to idolatry. Once the ancient religion had died out, so icons became much less fraught with danger. But a strong subset of theologians continued to oppose them. Leo III had one particular concern: he was disturbed by the tendency of his subjects to treat icons as though they were magic. During the siege, the patriarch of Constantinople had taken the most venerated icon in Constantinople, the Hodegetria (a portrait of Mary that was said to have been painted by the apostle Luke himself), and paraded around the walls with it. Miraculously, the city was saved, as if the icon was a sorcerer’s wand waved over the enemy. Such thinking had no place in Christianity. Perhaps Leo also felt some, not justified, indignation in seeing the praise for his hard-won victory given to the icon. Still, his actions over the next few years, which nearly cost him the throne, were those of a man acting against his own best interests; something explained only by deep conviction. In 726, Leo began to tentatively wean the people away from their over-reliance on the icons; he order the icon of Christ at the main entrance to imperial palace replaced with a simple cross. His fears were immediately justified. When the icon began to come down, a mob gathered and rioted. A persecution of those who resisted the removal of icons followed, though its enforcement was always more marked at Constantinople than in the provinces. The unrest spread with astonishing speed. The army of the military theme in Greece revolted, and proclaimed their own emperor, declaring that they could not follow a man who attacked holy icons. The rebellion was short-lived, but feelings continued to run high. In every city across the empire, iconoclasts ("icon-smashers") and iconophiles ("icon-lovers") argued; some bishops removed icons from their churches, while other bishops wrote long treatises defending their use. And, like all theological debates, the use of icons had a political edge: iconophiles sniped that the emperor was too much influenced by Islam, which was famously strict in forbidding images of living things. To the west, Pope Gregory II waxed indignant. He was himself a supporter of icons, but the more central issue was the emperor’s willingness to make theological pronouncements. More seriously, the pope ordered his own flock to ignore the imperial decrees to remove icons. By this time, only a handful of cities in Italy still retained loyalty to Byzantium; among them, Ravenna, Naples, Venice, and Sutri (south of Rome). The pope’s condemnation meant that these people now had a theological justification for finally deserting Constantinople. In Naples, the duke actually tried to carry out the emperor’s command, and was killed by an indignant mob. Meanwhile, the Lombard king Liutprand saw the opportunity to profit at the emperor’s expense. In 728, he attacked Sutri, took control of the city, and then offered to turn it over to the pope. Although known as the Donation of Sutri, it was not, in fact, a "donation"; the pope handed over a good deal of money in exchange. But everyone benefitted. Undeterred, in 730, the emperor Leo III issued a formal edict ordering the destruction of icons all across the empire. The pope responded by calling an ecumenical council, and excommunicating all the iconoclasts. Leo III, in return, announced that the handful of Byzantine possessions left in Italy were no longer subject to the pope's authority; instead, they fell within the sea of the patriarch of Constantinople. And the eastern and western branches of the church were drawn that little farther apart. Leo III died in 741, but the empire was no better off for his death; he was succeeded by his son Constantine V (741-775), who was even more rabidly iconoclast than his father. During his long reign, Constantine presided over the iconoclast movement at its peak. Persecution became fiercest, and there were martyrs, particularly among monks, who tended to defend icons more vigorously than did the secular priests. In these years, internal disorder within the Muslim world played into Byzantine hands, as the Abbāsid house fought to seize the caliphate. With his enemy thus weakened, Constantine was able to win noteworthy victories in northern Syria; thus iconoclasm became associated with military success and divine favour. Like his father, he settled the prisoners he had captured on the Thracian frontier. The First Bulgarian Kingdom had been more or less allies of Byzantium, ever since helping Leo III lift the siege of Constantinople back in 718. But the influx of settlers, crowding the Bulgarian borders, annoyed the Bulgarian khans. In retaliation, they began to raid Byzantine land. In 775, Constantine decided that they needed to be put in his place. But, as he was preparing his campaign, he fell ill and died. His successors all but let slip the gains won by the two great iconoclast emperors.

Empress Irene is a marker of the real authority which imperial women were capable of exercising in the Byzantine world. She was part of a succession of major figures, from Theodora (Justinian's wife) and emperor-maker Sophia (Justin II's widow) in the sixth century, through Martina (Heraclius’ widow) in the seventh, to Theodora (Theophilus' widow) in the ninth, and on to the empress-regnants Zoe and Theodora in the eleventh; even if Irene's eventual overthrow marks the fragility of female power as well.

Not much can be said about Constantine’s son Leo IV (775-780), as he is often considered as an appendage to his redoubtable wife, Empress Irene (d. 802). Why Leo chose her is a mystery. It has been suggested that she may have been plucked out of the obscurity of her native Athens (now an insignificant provincial town) through an empire-wide beauty contest. This curious Byzantine custom for choosing an imperial bride did occur on several occasions, though there is no actual evidence for Irene. Like most Athenians, Irene was a fervent supporter of icons. and she immediately influenced state policy by tempering her husband's persecution of iconophiles. Leo's short reign came to an end when he was stricken with a violent fever. He died, leaving a ten-year-old son Constantine VI (780-797). Irene immediately declared herself regent, and, for the next eleven years, was the effective ruler of the empire. From the outset, she seems to have taken more power than was traditionally expected of female regents. Coins depict both herself and her son, listing them, not as ruler and regent, but as co-rulers. Her position was not, however, undisputed. The army in Anatolia, overwhelmingly iconoclast, mutinied in favour of Leo IV's half-brother Nikephoros. The revolt was quickly put down, and Nikephoros scourged, forcibly ordained, and exiled to a monastery. But despite further unrest, Irene pressed on with her religious policy. When the iconoclast patriarch fell ill and resigned in 784, she had her partisan Tarasius elected in his place. A former civil servant and diplomat rather than a churchman, his approach to the iconoclast issue was that of a seasoned statesman. Much of the short-term success of the iconophile reaction was down to his pragmatism and judgement. The first priority, he decided, must be the restoration of relations with Rome. When an ecumenical council, with delegates from both east and west, met in Constantinople in 786, it was broken-up by iconoclast soldiers in the city. The pope was deeply shaken, but Irene and Tarasius acted quickly. The mutinous troops were dispatched to Anatolia on the pretext of an expedition against the Arabs; once there, their place in the capital was taken by more trustworthy regiments from Thrace. The ecumenical council then reconvened at Nicaea, the scene of Constantine's very first council in 325, where the veneration of icons was formally revived. Iconoclasts were not necessarily instantly converted to iconophiles; many high offices of Church and State, with most of the army, were still in iconoclast hands, and Irene seems to have moved with caution in deference to their sensibilities. In the meantime, Empress Irene showed no sign of relinquishing power, even though her seventeen-year-old son had reached the age of majority. Thenceforth Constantine VI found himself the rallying-point of all her enemies, In 890, Irene finally overreached herself. Instead of associating her son more closely with power, she now decreed that her name would take precedence in the army's oath of fidelity. Anger at this demand prompted open revolt. In Anatolia, one theme after another imprisoned their commander (strategoi), an appointee of Irene, and then acclaimed Constantine VI as the sole emperor. With military support, Constantine VI finally came to actual power. His supremacy was undisputed, his mother banished from court, and his popularity greater than ever. And he threw it away. The youthful emperor struck the caliph Harun al-Rashid as an opportunity to launch a new offensive into Anatolia. The Arab armies swept all the way to the Bosphorus Strait, and set up a camp at the port city of Chrysopolis, right across the water from Constantinople. This was embarrassing for Constantine, who had to agree to an enormous annual tribute in order to get him to withdraw. Then, when hostilities broke-out with the Bulgarians, he proved incapable of command, suffering a severe defeat at Markellai, in which he ignominiously fled the field. Thus, in January 792, Constantine VI recalled his mother as his co-ruler. For the iconoclasts old guard in Constantinople, this was the last straw. A new plot was hatched to bring Leo IV's half-brother Nikephoros out of retirement and make him emperor. For once in his life, Constantine responded to the threat with decision; perhaps on his mother's advice. He not only had Nikephoros blinded, but cut-out the tongues of his four brothers. Her advice resulted in a full-scale revolt. Naturally, the Anatolian themes were hardly pleased with this turn of events. An expedition made against their revolt was defeated in November, but it was finally quelled in May of the next year. By now, one group only was prepared to support Constantine VI; the monasteries. But in 795, they learned to their horror of the emperor had committed adultery. Constantine had always disliked his wife, Maria, perhaps because she had been his mother's choice. He had long ago given his heart to Theodot, one of the court ladies. Irene must have been aware of the liaison; and perhaps encouraged it. Certainly she made no objection when Mary was packed off to a nunnery, and the emperor promptly married his mistress. As Irene had doubtless foreseen, the clergy strongly disapproved of this marriage, the legality of which was hotly debated. Constantine VI had forfeited his last remaining supporters, and was now defenceless against his formidable mother. In 797, she was ready to strike. Her supporters captured the twenty-six-year-old emperor, and imprisoned him in the purple chamber of the palace, where he had been born. There, Constantine VI was blinded "in a cruel and grievous manner to ensure that he would not survive". There can be no doubt that Irene was guilty of his murder. Since Constantine's only son had died in infancy, she was now the sole occupant of the imperial throne; the first Byznatine empress to rule in her own right. It was a position which Irene had long sought; but one that she had little opportunity to enjoy. The fact that the eastern throne was held solely by a woman doubtless encouraged Charlemagne to assume the imperial title; he was crowned by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day, 800. Within Constantinople too there were clearly concerns about her fitness to rule. Whatever the degree of Constantine VI's unpopularity, his murder was generally abhorred. The brothers of Leo IV were again the centre of a series of plots; resulting in the four as yet unblinded all losing their eyes. Irene also attempted to buy popularity by granting enormous tax remissions, which the empire could ill afford; but this could only delay the inevitable. By 802, her subjects despised her, her advisers were at each other's throats, her treasury was exhausted. According to Theophanes, who alone mentions it, Irene considered a marriage between herself and Charlemagne. It mattered little to her that her suitor was a rival emperor, nor that he was in her eyes an illiterate barbarian; by marrying him she would save her own skin. Maybe so. But it was not to be. On the last day of October 802 a group of high-ranking officials summoned an assembly in the Hippodrome and declared her deposed. Empress Irene accepted her exile to Lesbos with dignity; and a year later she was dead.

Krum the Fearsome was responsible for the deaths of two Byzantine emperors, and the downfall of a third; and the overwhelming defeat of two imperial armies. His able, energetic rule rocketed Bulgaria into a position as (probably) the third greatest kingdom of Europe.

The veneration of icons, nonetheless, lasted through the reigns of Irene's three immediate successors. The new emperor was the leader of the coup against her: the able finance minister Nicephorus I (802-811). Few men were better qualified to set Byzantium back on its feet after Irene's chaotic reign. His heavy taxes and strict control of finances were not particularly popular, but the economy was soon on a sounder footing than it had been for years. It came just in time, for this decade saw the rise of Krum the Fearsome (803–814), the most formidable khan the Bulgarians had ever produced. Around 805, Krum thoroughly defeated the once-mighty Avars (who had already suffered a crippling blow from Charlemagne in 796), and then folded their territory into his own. This prompted Nikephoros to confront the Bulgarian khan, before he became even more powerful. It took him almost two-year to get his troops on the road, partly because he had deal with a revolt at home in the middle of his preparations; his choice of a moderate patriarch (also named Nicephorus) was challenged by the hardline iconophile wing of the church. But by 808, he was moving troops into the Strymon valley, on the southern Bulgarian border. Krum descended on them before they were at full strength, scattered the army, and seized the baggage train, including all the money sent along for payroll; eleven hundred pounds of gold, according to Theophanes. Hostilities now began in earnest. In 809, Krum led his army against the frontier city of Serdica (modern Sofia), and captured it, slaughtering its garrison of six-thousand. Such an atrocity could not go unpunished. Once again it took Nicephorus almost two-year to prepare what he was determined would be his decisive campaign against Krum. This time, he was distracted by perhaps his most consequential reform; the wholesale resettlement of Greece. In the sixth century, the region had been occupied by the Slavs, who had, fortunately, given little trouble. But the rise of the Bulgarians presented a new danger; one huge Slavonic bloc, extending from the Danube to Peloponnese, was not a pleasant prospect. Nicephorus' edict transferred soldiers and their families between the great themes of Anatolia, and those of Greece and Macedonia; perhaps seventy-thousand men, women, and children. The actual aims was to remove potentially rebellious soldiers by stationing them with different units, but the effect was to change Greece from a primarily Slavic land back to Greek; without it the history of the Balkans might have been different indeed. In 811, an immense Byzantine army finally left Constantinople, with Nikephoros and his son Stauracius at its head. They marched towards Krum’s capital at Pliska, just west of the Black Sea; and found it virtually undefended. The emperor ordered his men to burn the khan's wooden palace to ashes, and slaughter the population; "He ordered that senseless animals, infants, and persons of all ages should be slain without mercy,” Theophanes writes. He had the upper hand, and refused to listen to Krum's messages suggesting a truce. But the khan was not finished. He had retreated, along with every man he could muster, into the mountains through which the Byzantine army would have to march on their way home, and built a wooden palisade across the pass. On July 25, heading for Constantinople in triumph, Nikephoros and his men ran directly into the wooden wall; and the Bulgarians attacked the trapped army. Nikephoros, fighting at the front, was killed almost at once; most of his army was cut to pieces; of the remainder, many were burnt to death when the Bulgarians fired the palisade. Krum turned out to be no more gracious in victory than his opponent. He beheaded the emperor’s corpse, had the skull coated in silver, and used it as a drinking cup. A few men had managed to escape, chiefly cavalry; among them Nikephoros’ son Staurakios, badly wounded by a blow to his spine. His companions hauled him back to Constantinople, where he was crowned emperor in his father’s place. But he soon sank into paralysis. By October, he was forced to give power over to his brother-in-law Michael Rangabe (811-813), who faired little better. In only one respect does he occupy a place in Byzantine history. Michael was the first emperor to acknowledge Charlemagne’s imperial status. Perhaps, on reflection, the Frankish king seemed not so bad after all. He might be presumptuous, but he was Christian, and at least two centuries past using an enemy's corpse for tableware. The language of the acknowledgement reveals its grudging nature; Michael hailed Charlemagne, not as emperor of the Romans, but emperor of the Franks. Reassured that Krum would now find an enemy at his back, Michael resumed the battle against the Bulgarians, who had begun to approach Constantinople itself. After initial success in spring of 813, he prepared for a massive, war-ending confrontation at Versinikia near Adrianople in June. The commander of the left wing, a man named John Aplakes, led the attack, and the Bulgarians fell back in confusion. For a moment, it looked as if the battle might be over almost before it had begun. But then an astonishing thing happened: the right wing,, commanded by Leo the Armenian, suddenly turned tail and fled the field. With conspiracy in the air, the emperor Michael Rangabe promptly followed him back to Constnatinople. At first, we are told, Krum stood incredulous; then he and his men fell on the luckless John Aplakes, and slaughtered his men wholesale. What had actually happened? The only reasonable explanation is treachery. Discredited by defeat, Michael pre-empted events by abdicating the throne, and withdrawing to a monastery. The Byzantine throne was taken by Leo as Emperor Leo V (813-820). He provides evidence enough of the degree to which even the highest office lay open to the man with the wit and strong-character to seize it. In the meantime, the path to Constantinople lay open to the Bulgarians. On the way, most of the fortresses surrendered without a fight; only Adrianople resisted. Leaving his brother to lay siege to the city, Krum advanced to the Byzantine capital, where he terrified the city, not least by performing an impressive pagan sacrifice right under the Theodosian Walls. After a token siege, the Bulgarian khan agreed to negotiate a truce under a flag of parlay. But Leo V had no intention of honouring the conventions of such meetings; conventions governed Christian kings, not treating with barbarians. When Krum approached the meeting place, just outside the Golden Gate, Leo’s men tried to assassinate him. Although wounded, he managed to escape. His revenge began on the following day. The Bulgarians could not penetrate the walls, but the suburbs, with all their churches, palaces and monasteries, were reduced to smouldering ashes. Krum then turned on Adrianople. For some weeks already the city had been under siege; food was running out, and the arrival of the main body of the khan's army finally broke its resolve. All of its ten-thousand inhabitants were carried off to Bulgaria as a constant reminders of the Byzantine treachery. Krum was making massive preparations for a second assault on Constantinople when, in 814, he died, most likely of a stroke. Without Krum’s fury behind it, the Bulgarian juggernaut lost some of its momentum. His son, Omurtag (d. 831), concluded a thirty-year peace treaty with the Byzantines, in order to secure his throne and consolidate his holdings. Under his father, the Bulgarian territory had doubled in size, spreading from Adrianople to the Tatra Mountains, and from the middle Danube to the Dnieper. With the help of Christianity, which was already spreading through the population from Byzantine captives, the descendents of Krum (who ruled without interruption for a century) would begin to shape the Bulgarian horde into a state that could take its place among the major powers of Europe.

From 843, icons recovered their special position in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, never again to lose it. In an Orthodox church, a screen (iconostasis), dedicated to the display of icons and religious paintings, seperates the nave from the altar sanctuary. As other regions are converted to the Byzantine tradition, in the Balkans and in Russia, the veneration of icons spreads. Indeed to many people nowadays, after a millennium of the rich tradition of Russian Orthodox Christianity, the word "icon" suggests first and foremost a Russian religious painting. And Russian icons, still being painted today, preserve much of the ancient Byzantine style.

With peace, Emperor Leo V was free at last to pursue the policy for which he is best remembered; the second wave of iconoclasm. His reasons were very different from those of his namesake eighty-eight years before. Leo III had a genuine religious conviction; Leo V's primary concern was purely practical. Constantinople was by now full of destitute peasant, driven from the eastern provinces by Arab incursions during the Bulgarian wars. Being easterners, these men tended to be iconoclasts; they tended, moreover, to blame Irene and her iconophile successors for their misfortunes. For the sake of public order, Leo convened a general synod at Constantinople in 815; to which a considerable number of iconophile bishops failed to receive an invitation. With the patriarch deposed and iconoclasm once again reinstated, the emperor undertook no stringent persecution of icon-lovers. He exiled his most vociferous opponent, Abbot Theodore, but most iconophiles found that, provided they kept a suitably low profile, they could carry on as before. And yet, inevitably, the synod of 815 unleashed a new wave of destruction. Anyone could set to work on icons with whitewash and hammer at any time, without fear of punishment. The artistic loss from these two periods of iconoclasm must have been immense. Leo V had always rewarded his supporters in the army. However, this policy backfired when Michael, one of his most trusted allies, had the emperor murdered during Christmas mass in 820, Actually, Michael was rather pushed into his dramatic action, as he had been condemned to death by Leo the day before; the novel method decided upon involved hurling him into the huge furnace that heated the baths of the palace. Michael then ascended the throne as Michael II (820-829). Many other men, to be sure, had become emperor with blood on their hands; none, however, had dispatched his predecessor more cold-bloodedly. And yet, Michael was to prove a better ruler than anyone could have expected. He immediately elevated his seventeen-year-old son Theophilus co-emperor. He was deeply conscious that, of his immediate predecessors, two had been deposed, two killed in battle, and two murdered. More than anything the empire needed stability; his son and his grandson would each occupy the throne in turn, not that anyone would have forecast so happy a future during Michael’s first years. He faced the long revolt of a charismatic adventurer known as Thomas the Slav, who appeal to just about every group who might have a grievance against the emperor; a champion of the overtaxed poor, of iconophiles who resented Michael's (albeit moderate) stance against icons, and even of old supporters of the murdered Constantine VI. What his innumerable followers did not know was that Thomas was enjoying considerable financial support from Caliph al-Mamun. Crucially, Thomas could also call upon the naval fleet along the coast of Anatolia, and the height of the crisis came when he besieged Constantinople in December 821. Winter storms saw off the initial attacks, and then Krum's son Omortag who, having concluded a thirty-year truce, offered to help break the stalemate. In the spring of 823, Thomas' army was crushed on the plain of Keduktos near Heraclea, and swept up by Michael's forces riding out from the capital. Escaping with a handful of followers, Thomas fled to the fortified town of Arcadiopolis, and barricaded himself inside. Now the besieger had become the besieged. He held out for a few months, but, when Michael offered a pardon if Thomas was handed over, his men agreed. Thus, the would-be usurper was captured and executed; his body was impaled on a stake, after having his hands and feet cut off. Emperor Michael II was the first emperor for half a century to die peacefully in his bed; the first, too, to leave a capable son to succeed him. Inheriting the throne at the age of twenty-five, Theophilus (829-842) was seen as a new hope for the empire. A return to former glories was not to be, but at least Theophilus was popular because of his exuberant personality, even once participating in a chariot race in the Hippodrome; which he won, of course. He also earned a reputation for his love of justice, especially when he introduced the custom of riding from the palace to the church at Blachernae on Fridays (one end of the city to the other), in the course of which any subject could approach him with complaints of unfair treatment. If ever an emperor knew how to market to his people the good times were here again, it was Theophilus. But in a sad stroke of irony, he passed almost the whole of his reign in warfare against the Muslims. An Arab army defeat the emperor himself at Dazman in 838, as a prelude to the capture of the important fortress of Amorium in Anatolia. This may also explain the continuing collapse of Byzantine power in the Mediterranean, manifest in the capture of Crete in 826 and in the initiation of attacks upon Sicily that secured the island for the world of Islam. Theophilus shared his father's iconoclast convictions, though without his more conciliatory tone. But when, in 842, he died of dysentery at thirty-eight, and the age of iconoclasm died with him. Empress Theodora now found herself regent for their two-year-old son Michael III (842-867), Like Irene fifty-years before her, she presided over the restoration of icon veneration. Theodora moved with caution: John the Grammarian, a fervent iconoclast, was now firmly ensconced upon the patriarchal seat. But she was more intelligent than Irene had been, and was fortunate to have as her chief advisers three men of quite exceptional ability; her uncle Nicetiates, her brother Bardas and the eunuch Theoctistus. The first two shared her views, while Theoctistus, who had been an iconoclast up until recently, was above all a statesman. The four gave notice that a general synod would be summoned at Constantinople in March 843. The synod passed off smoothly enough, except that John the Grammarian refused to resign. Only after he had been forcibly deposed did he retire to his villa on the Bosphorus; and a monk named Methodius was elected in his place. Thus, on the first Sunday of Lent, the decrees of Seventh Ecumenical Council – that which had put an end to the first period of iconoclasm in 787 – were confirmed; a day still celebrated as a feast in the Eastern Orthodox Church. At Theodora's insistence, however, her dead husband's name was omitted from the lists of those prominent iconoclasts who were now condemned as heretics. The story, assiduously circulated, that he had repented on his deathbed can safely be discounted; but it solved a potentially embarrassing problem. The victory was won: and, as with so many victories, it owed its long-term success to the magnanimity shown by the victors. Despite many sufferings in the cause of his beloved icons, Patriarch Methodius showed no desire for vengeance; iconoclast leaders were never ill-treated or imprisoned. And it was more than two decades before the first figurative mosaic was unveiled; a huge, haunting image of the Virgin and Child in Hagia Sophia, which still gazes impassively down on us today. For the defeated iconoclast, one small consolation remained. After this time Byzantine art restricted itself to two dimensions; sculpture was set aside. This should not, perhaps, occasion us too much astonishment: the Second Commandment is clear enough. It is, nonetheless, a very real cause for regret. If Byzantium had gone on to produce sculptors and woodcarvers as talented as its painters and mosaicists, the world would have been enriched indeed.

Emperor Michael III would never quite escaped the shadow of his mother Theodora, or his uncle Bardas. Nevertheless, his reign saw significant political developments; the Byzantine economy stabilized; the empire more than held its own against the Abbasid caliphate; the definitive end to iconoclasm led, unsurprisingly, to a renaissance in visual arts; and The Rus' (Vikings) arrived on the Byzantine frontier. Michael was ultimately murdered and succeeded by the Emperor Basil. who would inaugurate a remarkable revival for the empire, sometimes dubbed the "golden age" of Byzantium.

Muslim Golden Age[]

The caliph Hisham (724-743) had tamed the turmoil of rebelling converts in the frontier lands. But the victories came at great financial cost; and although Khorasan had been reduced back into order, the order was precarious at best. When Hisham died of diphtheria, the Umayyad caliphate too began to die. He was succeeded by his nephew Walid II (743-744), a man reportedly more interested in earthly pleasures than in rule; a reputation that seems to be confirmed by his move out into the desert, not to live again the life of the Bedouin, but to enjoy his remote and luxurious palaces, equipped as they were with hot baths and great hunting enclosures. Walid was murdered by his cousin in less than a year; the cousin, Yazid III, lasted for six months and then grew ill. Just before his death, he named his brother Ibrahim to be his heir, but, before Ibrahim could consolidate power, the general Marwan swept down from Armenia with his army, drove out the opposition, and, in 744, had himself declared caliph, as Marwan II (744–750). He almost succeeded in pulling the empire back together; it had not been under bad leadership for very long, and he had Hisham’s twenty years of order to build on. But, profiting by the unstable conditions, the Byzantine emperor Constantine V went on the attack. He enjoyed many successes in northern Syria, and inflicted a serious defeat on the Arab fleet off Cyprus in 747. These defeats fueled the internal opposition to Marwan’s rule. Marwan, while distantly related to his predecessors, was still Umayyad. Ever since the death of the fourth caliph Ali (Muhammad’s son-in-law) back in 661, the caliphate had stayed within the Banu Umayya, the clan of Muhammad’s old companion Uthman. The Umayyad caliphs had ruled as Arabs over an Arab empire. For nearly a century, the strongest glue holding the Islamic conquests together had been Arabic culture: the Arabic language, Arab officials in high positions, a bureaucracy supported by the reimposed Jizya (“head tax”) on non-Arabs. The worship of Allah was, of course, inextricably entwined with Arabic culture. But the Umayyad caliphs were, in the final analysis, politicians more than prophets, soldiers more than worshippers. When fortune finally turned against them, their hold on power collapsed rapidly.

Abū al-ʿAbbās, also known al-Saffah, the first caliph of the new Abbasid caliphate, which would survive nearly two centuries (until 946) as a real power and even longer as a puppet regime.