| Crisis of the Roman Empire | |

| Period | Classical Antiquity |

| Dates | 180-305 AD |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by Early Roman Empire |

Followed by Christian Roman Empire |

| “ | One person's barbarian, is another person's "just doing what everybody else is doing." | ” |

–Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others | ||

The Crisis of the Roman Empire lasted from about 180 AD until 305 AD. It began with the accession of Commodus, which marked the opening a terrible era in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. It then ended with the reign of Emperor Diocletian, and his fundamental restructuring of Roman imperial government

The republic had died, but the empire had grown up to replace it, like a distant cousin with a faint family likeness. But now, with the death of Marcus Aurelius, the empire sickened; there would be no sixth "Good Emperor". His wretched son, Commodus, was assassinated in 192 AD, but that solved nothing. From the civil war that followed emerged an African-born emperor, Septimius Severus, who strove to base the empire again on heredity, linking his own family with Antonine emperors. This was really to deny the fact of his own success. Severus, like his rivals, had been the candidate of a provincial army. Soldiers were the real emperor-makers throughout the third century. Here was a dilemma that faced each new emperor. Severus’s son Caracalla, who prudently bribed the soldiers heavily, was none the less murdered by them. More military emperors followed him. Soon there was for the first time one who did not come from the senatorial ranks; Maximinus Thrax, the candidate of the Rhine legions, who contested the prize with an octogenarian with the backing of the African army. It was a dreadful century; altogether, twenty-two emperors came and went, and that number does not include mere pretenders; nor such as Postumus, who for an independent Gaul for the better part of a decade.

The fragility of the top position accelerated the effects of economic troubles, and particularly the major ill of the century, inflation. Its sources and extent are complex and still disputed, but, in part, it derived from an official debasement of the Roman coinage. Meanwhile, an army, whose size doubled in a century, had to be paid for by a population which had probably already begun to shrink, from the impact of the Antonine Plague. But if the northern barbarians were to be kept out, the soldiers had to be paid. The most important barbarian peoples involved were the Franks and Alemanni along the Rhine, and the Goths on the Danube; the latter actually killed an emperor in battle in 251 AD. The scale of these incursions is not easy to establish. Significantly, as the third century wore on, towns and cities well within the frontier began to build walls for their protection. Rome fortified herself soon after 270 AD. And there was not only the barbarian to contend with. Ever since the days of Sulla, a cold war with Parthia had flared up from time to time into full-scale conflicts. In the third century, Parthia disappeared, but the threat to Rome did not. A Persian king called Ardashir re-created the ancient Achaemenid empire under a new dynasty, the Sassanids; it would be Rome’s greatest antagonist for more than four hundred years.

The backbone of the Roman army was provided by recruits from Illyria (the western part of the Balkan); appropriately, it was a succession of Illyrian emperors who turned the tide. Much of what they did was simple good soldiering. Losses were cut; the province of Dacia, to the north of the Danube, was abandoned. Alliance with a prince of Palmyra helped to buy time. The army was reorganized to provide an effective mobile reserve, that could be dispatched anywhere in the empire in short order. This work all culminated in the reign of Aurelian, whom the Senate honoured as “Restorer of the World”. But the cost was heavy. A more fundamental reconstruction was needed if Aurelian’s achivements were to survive, and that was the aim of Diocletian. He had an administrator’s genius rather than a soldier’s. Without being especially innovative, he had an excellent grasp of organization, a love of order, and great skill in picking and trusting men to whom he could delegate. The heart of the reform was the Tetrarchy (“Rule of Four”), in which each colleague would rule-over a quarter of the empire. The intention was to manage administrative and military resources efficiently, to break the cycle of usurpers in remote provinces, and to make possible an orderly succession. In fact, the succession mechanism only operated once as intended. Without the guiding hand of Diocletian, the empire fell into a civil war, that ultimately left Constantine in control of the entire empire. Although Constantine ignored those aspects of Diocletian's reign that did not suit him, the administrative and financial reforms lasted, ensuring the continuity of the Roman Empire in the east for more than a thousand years.

History[]

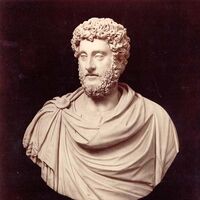

Emperor Commodus (180-192 AD)[]

Emperor Commodus, whose exploits in the arena were re-created, not wholly inaccurately, in the movie Gladiator.

In the view of Dio Cassius, a contemporary observer, the accession of Commodus (180-192 AD) marked the descent "from a kingdom of gold to one of rust and iron"; a famous comment which has led many historians, notably Edward Gibbon, to take his reign as the end of Rome's halcyon days. Commodus' reign would anyway have been difficult. The recent years of the Antonine Plague, and pressure on the northern frontier (including even a brief invasion of northern Italy), had left the Empire in an unsettled state. The situation was made more so by his own behaviour. Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus was the first Emperor to be "born to the purple"; born during the reign of his father, Marcus Aurelius, and raised in the palace surrounded by indulgent sycophants. Although he enjoyed the benefit of an excellent educated, Commodus inherited none of his father's work ethic; his chief interest was athletic competition. He was named heir-apparent at the age of 5, and co-Emperor at 17, after which he accompanied his father on his campaign against invading Germanic tribes. Marcus died in 180 AD, leaving the Empire to a 19 year-old. The new Emperor remained with the Danube legions for only a short time, before negotiating peace with the Germans; a peace that held surprisingly well for almost 70 years. He then made haste for the ease and luxury of Rome. His arrival sparked the highest hopes; the youthful Commodus must have appeared in his Triumphal parade as an icon of new and happier days to come. Though the Senatorial order came to hate and fear him, he remained popular with the army and the common people for much of his reign; not least because of his lavish donatives (imperial handouts), and spectacular gladiatorial combats. Commodus embarrassed the games like no Emperor before or since; and the people loved him for it. At the outset of his reign, Commodus inherited many of his father's senior advisers. He seemed to find government life tedious, and tended throughout his reign to leave the practical running of the state to a succession of favourites, while he devoted his time to worldly pleasures. The first to assume the Emperor's responsibility was a freedman named Saoterus, who soon incurred the ire of the Senatorial order; taxing them heavily to pay for Commodus' largesse. Nevertheless, the first conspiracy of his reign did not come from Senators, but from the imperial household. Commodus' older sister Lucilla, as the widow of Emperor Lucius Verus, had held the rank of Augusta, "first woman of Rome". Resentful at her loss of status, in 182 AD, she and her lover attempted to murder Commodus as he entered the Colosseum. They bungled the job, and were seized by the Praetorian Guard; Lucilla was exiled to Capri and later killed. The attempt Commodus' life, though, had only been part of the plan; Saoterus was soon found dead. Commodus took the loss of his favourite badly, In the immediate aftermath, both Consuls and one of the two Praetorian commanders were executed, along with a number of other prominent Senators. In addition, dozens of his father's old advisors were dismissed from office; among them, Didius Julianus, a participant in the Year of Five Emperors. Similar purges would follow the rise and fall of Commodus' subsequent favourites; Perennis (d. 185) and Cleander (d. 190). Not since the end of Domitian's reign had the Roman elite lived under such a cloud of fear and paranoia. Meanwhile, the imperial treasury was increasingly feeling the effect of the Antonine Plague; manpower shortages in the economy; reduced tax revenue; and corresponding increased tax burden. Commodus and his favourites came up with various short-sighted solutions. First, the Roman currency was heavily debased; the denarius (the standard silver coin) to about 70 percent silver content. Although the long term effects of this on inflation seem to have been minimal, Commodus set a precedent for future emperors to continuously debase the coinage; by Diocletian's reign, the denarius was basically silver plated. And second, everything was for sale; from Senatorial seats to provincial governorships. The climax came in the year 190 AD, which saw 25 suffect Consuls; a record in the 1,000-year history of the Senate. The result was administrative and bureaucratic chaos; for fun and profit. The Empire was lucky during this period that Commodus' reign was relatively peaceful in a military sense; both the Parthians and Germans had recently been humbled; a brief uprising in Dacia was easily put-down by the combined efforts of Clodius Albinus and Pescennius Niger, two more participants in the fast approaching Year of Five Emperors; and a revolt among the legions in Britain quickly fizzled-out. Meanwhile, a series of conspiracies eventually convinced Commodus to take over the reins of government himself, which he did in an increasingly megalomaniac manner. He began to appear in public dress like the divine hero Heracles, wearing a lion skin and carrying a club. He imagined himself the new founder of Rome, renaming the city "Commodiana". All the months of the year were renamed to correspond exactly with his full name and title; now numbering twelve. And, to the surprise of everyone, he took his passion for gladiatorial combat to the amphitheatre, fighting as a gladiator; his opponents always submitted to the Emperor, so he never lost; his bested opponents were always spared. Rome as a whole decided that he must be the product of one of his mother’s (alleged) affairs; he could not possibly be a son of the saintly Marcus Aurelius.

After numerous fail plots and exposed conspiracies, some finally managed to kill Commodus. The conspirators - his mistress Marcia and two courtiers - had discovered their own names on list of people intended for execution. In December 192 AD, Marcia poison Commodus' food. When Commodus did not die fast enough, they went and fetched his wrestling partner Narcissus to strangle him to death; he was 31 years-old. A grateful Senate cursed Commodus' memory, and declared one of their own number, Publius Helvius Pertinax, as the new Emperor. But, rather than waking into the safety of a Commodus free world, the people of Rome would be forced to endure a political situation spinning violently out of control; a Year of Five Emperors.

Year of the Five Emperors (193 AD)[]

The civil war of 68 AD is remembered as the Year of Four Emperors. As a nob to the inflation, which would soon wreck the Roman economy, the year 193 AD had no less than five emperors. Clockwise from top left: Pertinax, Julianus, Niger and Albinus, with Septimius Severus in the centre.

At first, the Year of the Five Emperors closely echoed the last occasion when an Emperor had been murdered. Then, Domitian had been the victim, and Nerva the successor; and that introduced a century of stability. Like Nerva, Pertinax (d. 193 AD) was seen as a safe pair of hands. Like Nerva, he was an elder statesman (already 66 years-old), with no children, who had served with distinction under his predecessor. Unlike Nerva, he would not enjoy a peaceful end. When Commodus was murdered, the Senate met before dawn, and proclaimed Pertinax the new emperor. From there, he went to meet the Praetorian Guard, and promised to pay their customary bonus. However, the new emperor found that the excesses of Commodus had left the finances of the empire were in ruins. To rebuild the treasury, he sold everything he could; "the statues, the arms, the horses, the furniture" wrote Cassius Dio. Although he was eventually able to give the Praetorians the bonuses he had promised, he would never win their loyalty. Their resentment was compounded when Pertinax attempted to impose stricter discipline upon the pampered soldiers. In March, a contingent of some 300 Praetorians mutinied and stormed the palace. Although urged to flee, Pertinax attempted to reason with them. Whether his words were almost successful became irrelevant, when one overzealous soldier stabbed him to death; he reigned for 86 days. This rash act of violence left the Praetorian Guard in a tricky situation. The solution they came up with was one of the most notorious events in Roman history; they auctioned off the purple to the highest bidder. The winner was a wealthy senator named Didius Julianus (d. 193 AD). Although he bought his position, Julianus was not a complete moral bankrupt. He seems to have been motivated (at least in part) by a hope to avert civil war; in this, he was unsuccessful. The Senate duly confirmed Julianus, but disturbances broke out in the city, When news of the death of Pertinax and the public outrage in Rome spread across the Empire, three influential provincial governors declared themselves emperor. The first was Niger (d. 194 AD), born Gaius Pescennius Niger, the governor of Syria, and the preferred choice of many in Rome; he had four legions at his disposal, but chose to wait for his march on Rome until he could muster more support. Next came Albinus (d. 197 AD), born Clodius Albinus, the governor of Britain; he had three legions. Lastly, there was Severus (d. 211 AD), born Lucius Septimius Severus, a governor on the Danube, and the nearest to Rome; he began with only two legions, but proved to have the most cunning and daring. Declaring himself the avenger of Pertinax, Severus marched on Rome. Julianus responded by declaring him a public enemy, and sending assassins to no avail. When Severus entered Italy without resistance, Julianus ordered the Praetorian Guard to prepare for the defence of Rome, but his authority even within the city was rapidly deteriorating. In desperation, Julianus sent envoys to negotiate with his rival, but Severus ignored them and pressed on. Wary of taking Rome by force, Severus managed to send messages to the Praetorians, offering them a full pardon in exchange for the actual murderers of Pertinax; they complied, killing the ringleaders. That same day, 1 June, the Senate declared Julianus a public enemy, and recognized Severus as the new emperor. The former emperor was found and killed the next day. His last word, “But what evil have I done? Whom have I killed?”, proved the most memorable moment in his 66 day reign. Septimius Severus took possession of Rome without opposition, but the civil war was not yet over. He temporarily pacified his rival in Britain, Albinus, by offering him the title of Caesar, and, with it, the position of heir-apparent. With his rear safe, he moved east to confront his more formidable rival, Niger. Niger had been busy securing the support of the governors of Anatolia and Egypt, and mustering his forces at Byzantium in Thrace. And yet his military support was inferior to Severus'; Niger had 6 legions at his disposal, while Severus could, in theory, call upon all 16 legions of the Rhine-Danube frontier. Unable to maintain further advances into Europe, the fighting moved to Anatolia, where Niger suffered successive defeats at Cyzicus and Nicaea, and withdrew south. By February 194 AD, the governors of Anatolia and Syria had switched their loyalty to Severus, and Niger faced revolts even in Syria. He was decisively defeating at Battle of Issus (May 194 AD), and fled to Antioch. The Syrian capital, which only one year earlier had as Niger was proclaimed emperor, now waited in fear for the approach of a new master. Niger was captured and killed, while attempting to flee once more to Parthia. Afterwards, Severus felt secure enough to discard his erstwhile ally Albinus. He conferred the title of Caesar upon his eldest son Caracalla, provoking Albinus into open revolt. In early 196 AD, he crossed into Gaul with three legions, occupied the provincial capital at Lyon (Lugdunum), and enjoyed some initially military successes. But he was unable to do the one thing he needed to really challenge Severus; persuade the Rhine legions over to his cause. Back in Rome, the populace used the anonymity of the chariot races to express their resentment at renewed civil war, but Severus was undaunted. In early 197, he gathered his forces along the Danube, and then swept into Gaul. Albinus retreated to Lyon, where the two sides met in the decisive Battle of Lugdunum (197 AD). This battle is often considered the largest, hardest-fought, and bloodiest of all legion-on-legion clashes; involving some 115,000 men. The tide shifted many times during the course of the battle, with the outcome hanging in the balance, but Severus' superior cavalry swung the battle in his favour for the final time; Albinus committed suicide in the aftermath. With the defeat of his last rival, Severus revealed a penchant for cruelty that troubled even his fervent supporters: Albinus' body stripped and beheaded; his wife and children were killed, as were many of his supporters; and Lyon was sacked and plundered. A purge of the Senate soon followed. Severus' victory finally established him as sole emperor of the Roman Empire.

Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211 AD)[]

Septimius Severus was born in the Roman province of Africa (now Tunisia and western Libya). He is often considered the first true provincial emperor, as he was, not only born in the provinces, but into a family of non-Italian origin. He was also the first African emperor, though we can say little for certain about his ethnic origins; ancient writers made no comment on them. In our terms, the Romans were relatively race blind. That does not mean the ruling class was some liberal cultural melting pot. They were certainly snobbish about men from the provinces. Even Severus is said to have been so embarrassed by his sister's bad Latin accent that he sent her back home.

The reign of Septimius Severus (193-211 AD) planted the seeds that would develop into the highly militaristic and bureaucratic government of the later empire. Although he sought legitimacy by connecting himself to the Antonine dynasty - even declaring himself to be retrospectively adopted by the long-dead Marcus Aurelius - he in fact pursued completely different policies. As with Commodus, his relations with the Senate were never good. He was unpopular with them from the outset, having seized power with the help of the army. He then executed about thirty senatorial supporters of his rival Albinus. The dislike was mutual. Severus ignored the Senate (which declined rapidly in power), and recruited his officials from the equestrian order (middle class). Many provincials received advancement. while Italians lost many of their former privileges. Nonetheless, Severus was generally popular with the common people of Rome, having stamped out the rampant corruption of Commodus' reign. He paid special attention to the administration of justice. A diligent and conscientious judge, he appreciated legal reasoning and nurtured its development. His court employed the talents of the three renowned Roman lawyers - Papinian, Paulus, and Ulpian - who ushered in the classical period of Roman law. Severus was to be best-remembered for his reforms of the army. His first action, once in Rome, was to summon the Praetorian Guard to a ceremonial parade (without weapons), and then brought-out his own Danube legions to surround them. Having discredited themselves by auctioning their support to Julianus, every guard was dismissed, and replaced with his own loyal men. Henceforth, the Praetorians were not a group of pampered soldiers, but the elite of the legions; membership became a reward for exceptional service in the provinces. Severus did not forget about the men left out on the frontiers, increasing their annual pay by a half; most soldiers would have seen this as overdue, since their last pay rise was by Emperor Domitian in 84 AD. There was a substantial increase in the number of soldiers too; from 30 to 33 legions. But perhaps the most significant aspect of the Severan reforms was the “democratization” of the career-path; centurion emerged from the ranks. Thus, a simple Illyrian peasant might attain high position. These military reforms may well have raised army morale and performance, but also greatly increased ongoing military expenditure; and the financial burden on the civilian population. Severus' prudent administration allowed these burdens to be met during his own reign, but caused problems for all of his successors. Severus understood that the surest route to legitimacy for a Roman emperor was military glory; which did not come from victories over fellow Romans. In the summer of 197 AD, he once again travelled east, and invaded Parthia, on the mildest of provocations. Following in the footsteps of Trajan and Cassius, the legions moved down the Euphrates, sacking Seleucia and Ctesiphon along the way, He would have liked to have continued his campaigns deeper into the Parthian heartland, but was unable to capture the fortress of Hatra, even after two lengthy sieges. After coming to a face-saving peace agreement, Septimius declared victory, and returned home. There were also the usual defensive campaigns on the frontiers. The order Severus was able to impose on the empire failed to extend to his own family. His sons, Caracalla and Geta, displayed a reckless sibling rivalry. The emperor decided that the lack of responsibilities contributed to the ill-will. In 209 AD, he appointed his eldest son Caracalla to be co-emperor with his brother, and then took them on campaign in Britain to harass the Scots. Severus was now into his 60s, and suffering from chronic gout. He died in York (Eburacum) in February 211. His reign had lasted nearly 18 years, a duration that would not be matched until Diocletian.

Emperor Caracalla (211–217 AD)[]

Septimius Severus had once criticised Marcus Aurelius for not smothering his son Commodus with a pillow. So, it’s not without irony that his own son, Caracalla, prove another of Rome's worst rulers. Edward Gibbon called him "the common enemy of mankind".

The Roman Empire now had two brothers, Caracalla (211-217 AD) and Geta (209–211), as co-emperors; a situation that recalled events of half-a-century earlier, when step-brothers Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus officially shared the empire. Caracalla might well have been satisfied had Geta behaved like Verus, who deferred to his older brother in political matters. Geta, however, saw his authority as being truly equal with that of his brother. The pair were barely on speaking terms during the long trip back to Rome. Once in the city, the situation did not improve. Government ground to a halt as the two bickered on appointments and policy decisions. By the end of the year, Caracalla resolved to be rid of his brother. After at least one unsuccessful attempt at the Saturnalia festival, Geta was killed in late December 211 AD. One account claimed Geta was lured to come (without his bodyguards) to a meeting with their mother, Julia Domna, to discuss a possible reconciliation. When Geta arrived, Caracalla had his men murder him. Geta died in his mother's arms. After his brother’s death, Caracalla had a tricky time of it. He went to the Praetorian camp, and claimed that the murder had been in self-defence. But, for a long time, the emperor was not admitted. The soldiers were only placated by an enormous raise, both for the Praetorians and provincial legions. In order to pay for this raise, Caracalla debased the Roman coinage once again; the denarius to about 50 percent silver. There followed by the wholesale slaughter of Geta's supporters. The soldiers wreaked havoc in Rome for at least two weeks; "There was even murder done in the baths, and some were killed at dinner too". Cassius Dio claimed 20,000 people were killed, including the celebrated jurist Papinian; he added that adds it became a capital offence to even speak or write Geta's name. Then Caracalla announced a new law: all free residents of the empire were now Roman citizens. Three centuries earlier, Rome had indignantly gone to war at the suggestion that the Italians should be citizens; now the law passed without much debate or discussion. Why he chose to take this step, at precisely this moment, has puzzled historians ever since. One purpose for the edict, known as the Constitutio Antoniniana, might have been to allow greater standardization in the increasingly bureaucratic Roman state. Another purpose was a logical outcome of the fact that the provinces were becoming increasingly important to the empire's existence, and provincials were now able to think of themselves as equal partners. More practically, this edict meant that Caracalla could widen the tax-base and increase revenue, since various taxes only had to be paid by Roman citizens. Roman citizenship, in a way, had become a trade-off; legal protections in exchange for money. It was not a particularly bad bargain; or not yet, since taxes had not begun to spike. Caracalla spent little time in Rome after the spring of 213 AD. A visit to Upper Rhine frontier and a senseless massacre of an allied Germanic tribe occupied much of the rest of the year; ascribed by ancient sources to his love of military glory. Winter may have been spent in Rome, but, the following year, Caracalla made a tour of the eastern provinces, in preparation for a campaign against the tottering Parthia Empire. Along the way, the emperor displayed an increasing fascination with Alexander the Great. Admiration of the Macedonian conqueror was not unusual among Romans, but, in the case of Caracalla, it became a ludicrous obsession. He adopted the clothing, behaviour, travel route, and honorific Magnus ("the Great"). He even organized one legion into a Macedonian phalanx, and added an elephant division; element long obsolete in the Roman army. At the same time, he adopted the Eastern practice of representing the ruler as godlike; his favourite was the Egyptian god Serapis. Caracalla's eastern campaign seemed designed to harass Parthia's nearby vassal kings into switching their allegiance over to Rome. He probably wouldn’t have gotten away with this for very long, except that the Parthian king, Artabanus IV (213-224), was having troubles of his own. His brother had rebelled, and occupied Lower Mesopotamia, including Ctesiphon. Caracalla, seeing an opportunity, dispatched a message to Artabanus, offering to help him, in exchange for his daughter's hand in marriage. When Artabanus refused, seeing this as a rather lame attempt to lay claim to Parthia, Caracalla pursued an aggressive campaigns into Parthia in 216 AD. Between campaigning seasons, in the winter of 215-16 AD, Caracalla made a visit to Egypt, ostensibly to pay respects at Alexander's tomb. In Alexandria, they had produced a satirical play mocking Caracalla's claim that he had killed his brother Geta in self-defence; as well as his other pretensions. When he found out, Caracalla flew into a rage, and set his troops against the city for several days of looting and plunder. While in Egypt, he also visited the famous temple of Serapis, and fully participated in the cult's sacrifices. Caracalla’s religious eccentricity is said to prompted Macrinus (d. 218 AD), the commander of the Praetorian Guard, to end his reign. This he did on a journey to visit the temple of Luna, near the site of the Battle of Carrhae, when the emperor stopped on the side of the road to relieve himself; one of Macrinus' men killed him. Overcome with righteous indignation, Macrinus drew his sword and killed the man, which did away with the need to investigate the matter further. Three days later, the eastern legions proclaimed Macrinus to be the new emperor; his reign lasted a total of 14 months, before being succeeded by Caracalla's cousin Elagabalus.

Emperors Elagabalus (218-222 AD)[]

Macrinus proved to be moderate and conciliatory emperor. An able administrator, he lacked the legitimacy that might have allowed him to clean-up Caracalla's mess.

At the start of his brief reign, Macrinus (217-218 AD) faced several issues, which had been left behind by his predecessor. As Caracalla had a tendency towards military belligerence, rather than diplomacy, this left several conflicts for Macrinus to resolve. Moreover, Caracalla had been a profligate spender, and Rome's fiscal situation was dire. The new emperor was at first occupied by the threat of the Parthians. He moved east to the frontier, but found the situation not as advantageous as it had been previously. The Parthian king, Artabanus IV had managed to reinstate a degree of stability, and was now eager to avenge Caracalla's unprovoked attacks. The two armies met near the Roman city of Nisibis, and ended with a bloody Parthian victory. As a result, Macrinus was obliged to seek peace, paying the Parthians a huge sum in reparations. At the time, the Roman province of Dacia was also under threat, so any deal with Parthia would likely have been beneficial to Rome. By not returning to Rome in 217 AD, Macrinus opened himself to criticism. In the autumn, a violent thunderstorm caused widespread flooding, especially in the Forum and Colosseum. But grumblings in Rome were insignificant compared to the growing unease in the army. Macrinus began to overturn Caracalla's fiscal policies. One such measure introduced a two-tier pay system, in which new recruits received less money than veterans. Macrinus' goal seems to have been to return Rome to the relative economic stability that had been enjoyed under Severus; he also reversed Caracalla's currency debasement. But it came with a cost. Veteran soldiers viewed his reduced pay for new recruits, as a foreshadowing reductions in their own pay and privileges. A plot against him was soon organized by the Severan family. In an attempt to appear moderate, Macrinus had left the old imperial family in peace; allowing them free rein to connive their way back into power. By this time, Caracalla's influential mother, Julia Domna, was suffering from an advanced stage of breast cancer and soon died; but her sister, Julia Maesa, took up the fight. With discontent in the army, Julia Maesa seized the opportunity of her sister's funeral to parade her 14 year-old grandson, Varius Avitus Bassianus (known to history as Elagabalus), as the rightful heir to the throne; the boy looked something like Caracalla and was widely rumoured to be his illegitimate son. As the revolt gathered momentum, Macrinus marshalled his own loyal soldiers. The two sides met near Antioch in June 218 AD. Macrinus, an administrator rather than a general, was defeated. He tried to flee back to Rome to regroup, but was captured and killed.

Ancient sources portrayed the failure of Elagabalus' reign as clash between Eastern and Roman cultures. But he is best understood as a teenager, who had been raise near the luxury of the imperial court, and lacked the required discipline for the imperial throne. Criticism of the emperor's bizarrely self-indulgent behaviour mirrors that of earlier Roman rulers, such as Nero, and do not need to be explained through ethnic stereotypes. With regard to religion, the emperor's promotion of the Syrian sun-god was certainly ridiculed by contemporaries, but that "mystery cult" had reached Rome before Elagabalus and remained popular afterwards. Indeed, the Syrian deity would assimilate with the Roman sun-god, known as Sol Invictus ("the unconquered sun").

The new emperor was born Varius Avitus Bassianus, but is better known by his nickname Elagabalus (218-222); the name of the Syrian sun-god. Since his early youth, he had served as high-priest of that cult; his imprudently promotion of his religion was among the many things that made him an object of scorn and ridicule to the Roman elite. Elagabalus was the first emperors from the Eastern provinces; he not only born there but culturally Eastern. Before his arrival in Rome, his grandmother Julia Maesa, the real power behind the throne, felt the need to send ahead a painting of him, so people would not be surprised by his Eastern garb. To further ease anxiety, almost immediately upon his entry into Rome, the young emperor married into a Roman aristocratic family. Unfortunately, Elagabalus demonstrated little interest in his wife; becoming involved in a series of homosexual liaisons, most notably with the charioteer Hierocles. Many of these favourites were given high-offices-of-state, offending aristocrats, bureaucrats and troops alike. His personal style was considered effeminate; silks, jewellery, perfume. Rumours were rampant that he wandered the streets of Rome at night dressed as a woman. The first crisis of his reign came in 220 AD, when Elagabalus divorced his wife to marry a Vestal Virgin named Aquilia Severa; perhaps the symbolism of a priest marrying a priestess seemed irresistible. Most Romans viewed the union as sacrilegious, and it was quickly dissolved. By 221 AD, the emperor was finding his actions increasingly restricted. An army revolt and at least one failed assassination attempt forced Elagabalus to remove many of his favourites from office. He remarried, this time to a great-granddaughter of Marcus Aurelius. He was also being undermined by his grandmother Julia Maesa, who had realized that Elagabalus was completely unsuited for the throne. She began to favour his cousin, Alexander Severus, and, in the summer of 221 AD, persuaded the childless emperor to adopt him as his heir. However, Elagabalus soon came to see his cousin as a threat. By early 222 AD, the government was approaching gridlock with officials split between two rival camps at court; Elagabalus and his mother on one side, Alexander and his grandmother on the other. As a few failed attempts on Alexander's life, in March 222 AD, Elagabalus ordered the Praetorian Guard to arrest and execute him. This proved the last straw. The Guard mutinied, and killed Elagabalus; he was just 18 years-old. His body was dumped into the Tiber, his memories damned. and Alexander Severus proclaimed emperor.

Parthia Falls to the Sassanids[]

On several occasions, during the second century AD, the Romans invade the Parthian Empire (247–224 AD), sometimes even reaching Ctesiphon and beyond. They were never able to hold any territorial gains beyond the Euphrates for long, but their incursions weakened the Parthian royal dynasty. Frequent civil wars between Parthian contenders to the throne proved even more dangerous to the Empire's stability than foreign invasion. In 222 AD, the same year as Elagabalus’ murder, the Parthian king Artabanus IV finally managed to defeat his rebellious brother, and take back Ctesiphon. He held his capital city for only two years. The Parthian Empire, which had evolved from a nomadic takeover, operated in a feudal fashion; the kings headed a loose hierarchy of powerful local dynasties. One such dynasty, that of the Sassanids, brought the Parthian Empire to an end. Repeating a pattern eight centuries old (when Cyrus overthrew the Medes), the rebellious feudal vassal came from the most ancient land of Persia, the province of Fars; the word "Persia" derives from the earlier form Pârs. He was Ardashir I (d. 242 AD), a king with strong links to the ancient Persian religion. His father was high priest of a temple to Zoroaster in the region of ruined Persepolis, before he killed the local ruler and took his place. Ardashir inherits this petty kingdom and enlarges it - demanding fealty from the local princes - until he was in a position to be crowned king of Fars in about 208 AD. With the Parthians engaged in yet another dynastic struggle, Ardashir then began rapidly gaining control over the neighbouring provinces. This expansion eventually came to the attention of Artabanus IV, the Parthian king, who initially ordered the governor of Susa to destroy this up-start in 224 AD; but Ardashir was victorious in the ensuing battle. In a second attempt, Artabanus himself met Ardashir at the Battle at Hormozgan (April 224), with the Persian king being, not only defeated, but killed. This marked the end of the Parthian era, and the start of 427-years of the Sassanid Empire (224-651). Ardashir's first order of business was to unite the disparate regions of the empire, and crush any resistance; both of which he accomplished between 224-227 AD. During this same time, he commissioned a number of building projects. His victory at Hormozgan was celebrated by two great reliefs at the Sassanid royal city of Gur (present-day Firuzabad), sculpted high in the rock face; the first depicts Ardashir on horseback, with a dead Parthian beneath his horse's hooves; the second displays him receiving the royal crown the Zoroastrian supreme god, Ahura Mazda. He also rebuilt the city of Ctesiphon, which became the Sassanid capital. With the restoration of the first authentically Persian dynasty since the Achaemenids, Ardashir organized his new empire into something more along old Persian lines; he assumed the ancient Achaemenid title of shahanshah ("King of Kings"); he divided the territory into provinces, or satrapies, that were intentionally laid out across the old vassal-kingdom borders; military governors of provinces were members of his own royal Sassanid clan; Zoroastrianism was proclaimed the official state religion; the religious hierarchy, with with chief priests for each province and a supreme priest wielding overall authority, became an important part of a complex and centralized bureaucracy; and kingship had no hesitation in claiming a divinely sanctioned right to rule (unlike Rome, there was no negotiating around the sensibilities of his subjects). The Romans had grown used to dealing with the tottering Parthians, and so were ill-prepared for the resurrection of a new Persian empire, which was strong enough to make demands.

Emperor Alexander Severus (222–235 AD)[]

Severus Alexander was a youth when chance brought him to the throne, with only two recommendations; that he was not Elagabalus and that he was a member of the Severan family. He did the best he could, but that best was not good enough in the early decades of the third century AD, with great threats from east and north challenging Rome's prestige, nay existence.

Alexander Severus (222–235 AD) was hailed emperor by the Praetorian Guard (and confirmed by the Senate) at just 13 years-old. Having had no experience in government, he was largely dependent upon the two women; his grandmother, Julia Maesa, before her death in 224 AD; and his mother, Julia Mamaea. The young emperor was a mild-tempered and serious, and the two senior women attempted to guide him well. Perhaps the greatest service which Alexander furnished Rome, certainly at the beginning of his reign, was the return to a sense of sanity and tradition, after the madness of Elagabalus. Guided by the two senior women, he put together a governing council of sixteen distinguished men to help with the day-to-day running of the empire. Together, emperor and council did much to improve the morals and condition of the people, and return dignity to the state; and to the imperial household. But military experience was the key attribute of an emperor now, and Alexander had none. His reign was characterized by a marked breakdown of military discipline. In 224 AD, the Praetorian Guard went so far as to murdered their commander, the jurist Ulpian, for curtailing privileges granted to them by Elagabalus; the deed was done in the imperial palace, in Alexander's presence. The emperor could not even openly punish the ringleaders; though, in time, he did transfer them away from Rome and quietly have them killed. Another member of the council, the historian Cassius Dio, retired from public life around 229 AD, to avoid being murdered by the Guard. Had his reign been peaceful. Alexander Severus might have developed into a good emperor. But much of his last decade was preoccupied with serious external challenges. The first threat appeared in the east, where the Parthians, who had long been Rome's great rival, were overthrown by the Persian family of the Sassanids by 227 AD. They aspired to restore the glory days of ancient Achaemenid Persia. Since their domain had included Anatolia, as well as all other eastern provinces, the stage was set for continuing clashes with Rome. In 230 AD, the first Sassanid king, Ardashir I, began a series of incursions into Rome's eastern provinces, penetrating possibly as far as Syria, and forcing from young Alexander a vigorous response. In 232 AD, the Romans launched a three-pronged counteroffensive; one army pushed into northern Persia through Armenia; another moved down the Euphrates towards Ctesiphon; and the force under Alexander's personal command remained as a reserve to support either one. Unfortunately, the extreme caution of the emperor, and the lack of a coordinated attack, resulted in heavy losses and what could only be called a fiasco. Although he could claim a "qualified success" - since the heavy losses suffered by the Sassanids forced them to withdraw - the army began to lose faith in their emperor. Shortly afterwards, his presence was required against a new and menacing northern enemy. In 233 AD, the Germanic tribes took advantage of the withdrawal of the legions for the eastern campaign to cross the Rhine and Danube, and plunder Roman territory. The soldiers, returning from their costly war against the Persians, were further demoralized on discovering their own homes destroyed by barbarian incursions. By the time Alexander, and Julia Mammaea, arrived at Mainz (Moguntiacum), the capital of the Upper Rhine, the military situation had settled. Again, he entered the fight without a definite plan. The legions had prepared heavily for an ambitious offensive campaign. However, due to the losses against the Persians and on the advice of his mother, Alexander attempted to buy-off the Germanic tribes, so as to gain time. This policy outraged the soldiers, who mutinied in March 235 AD, killing Alexander Severus and his mother. He had reached the age of 26 years and had been emperor for almost precisely half his life. With the accession of Maximinus Thrax, the Severan dynasty came to an end.

Alexander was the first emperor to be overthrown by military discontent on a wide scale. After his death, his economic policies were completely discarded, the average reign of an emperor plunged to roughly two years, usurpers popped-up with alarming frequency, and the loyalty of the legions turned on a dime. This signalled the most chaotic three decades of the Crisis of the Third Century, which brought the empire to the brink of collapse.

Emperors Thrax to Decius (235-251 AD)[]

Maximinus Thrax was the first of the "soldier-emperors". Although Rome's senatorial elite was eventually able to bring about the downfall of this humbly born career soldiier, their victory was only a temporary check on the rising importance of the military in the third century.

With the murder of Alexander Severus, the Roman army took matters into its own hands. The man they chose was Maximinus Thrax (235-238), a coarse but energetic career soldier from Thrace; the first of the "soldier-emperors". The new emperor spent most of his reign exacting revenge against the Germans along the Rhine-Danube frontier. The numerous milestones displaying his name attest to his energetic reconstructions of the roads in these regions. But he was seen by Rome's senatorial elite as a semi-barbarian, not even a true Roman; despite Caracalla’s edict granting citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire. Maximinus soon faced two coup attempts; the one involved a group of officers, supported by influential senators, who plotted to destroy a bridge across the Rhine, leaving strand Maximinus in hostile territory; the other, an uprising by disgruntled soldiers from Alexander's eastern campaign. Maximinus suppressed both of these plots, but his years of continual fighting were beginning to take a financial toll on the empire. Resentment finally boiled over early in 238 AD; the year became known as the Year of the Six Emperors. Attempts by a treasury official in the province of Africa to raise revenues through false judgments against local landowners ignited a full-scale popular revolt. The armed mob killed the official and proceeded to the governor of the province, the aged Gordian I, and proclaimed him emperor; alongside his son, Gordian II. When the news reached Rome, the Senate eagerly embraced the revolt. Maximinus immediately assembled his army, and marched on Rome. The swift collapse of the revolt in Africa did little to dampen the resolve of the Senate, who named two of their own as emperors; Pupienus and Balbinus. Unfortunately, the new emperors were not welcomed by the people of Rome; the Roman mob held no great regard for the senatorial elite. Rioting broke out; indeed, the co-emperors could not walk the streets without being hailed with stones and sticks. Meanwhile, Maximinus descended into Italy in spring 238 AD. The first Italian walled-city on his route to Rome was Aquileia, which closed its gates to him. His army became bogged down in a siege. Enraged by the delay, Maximinus took out his frustration on his own troops. In May, after little more than a month of siege, a group of his soldiers had had enough; they killed the emperor in his tent. The co-emperor, Pupienus and Balbinus, returned to Rome, only to find the rioting had intensified; most likely at the instigation of partisans of the Gordians. They had no option but to compromise, naming the grandson of Gordian I, young Gordian III, as heir-apparent. Although this had the effect of calming the Roman mob, mutual suspicions between the two emperors plagued their government from the outset, with each fearing assassination by the other. None of this escaped the watchful eyes of the Praetorian Guard, who resented serving under senatorial emperors. In July, the Guard stormed the palace, seized both emperors, and murdered them.

Gordian III was the youngest ever sole emperor, but his reign was not burdened by the troubles faced by other teenage emperors; such as Nero, Commodus and Elagabalus.

The young heir-apparent, Gordian III (238-244 AD), was proclaimed sole emperor; he was only 13 years-old. Due to his age, the imperial government remained in senatorial hands.Fortunately for Gordian and for Rome, a man who had risen through the military ranks, and had proven ability in imperial service, came to exert considerable influence on the young emperor. He was Timesitheus (d. 243 AD), who became the young emperor's Praetorian commander and father-in-law. Maintaining security along the frontiers remained the emperor's most serious challenge. Difficulties along the Danube continued, but the greater danger was in the east. An ailing Ardashir, the Persian king, captured the Roman frontier wall-cities of Nisibis and Carrhae (held for more than a generation), and then passed on to his son, Shapur I (240-270 AD, a well-organized empire, ready for expansion. Shapur advanced boldly into the province of Syria, and threatened its capital, Antioch. In 242 AD, Gordian accompanied Timesitheus on the counter-offensive, which saved Antioch and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Resaena (243 AD). Following this victory, the Romans recovered Nisibis and Carrhae. Before any further action could be taken, Timesitheus died of an illness. Without his father-in-law, the campaign and the emperor's security were at risk. Philip the Arab stepped in at this moment as the new Praetorian commander. When Gordian chose to march down the Euphrates towards Ctesiphon, Philip resisted. The campaign continued, but Shapur fought back fiercely, halting the Roman advance Battle of Misiche (244 AD). After the battle, Gordian died in unclear circumstances. Ancient sources universally blame Philip, either directly or by fomenting discontent against the emperor. When Philip refused an order, an enrage Gordian gave the troops a choice; him or Philip. They chose Philip. who was proclaimed Gordian III's successor by the army.

Depiction of Gothic warriors battling the Romans, from the Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus. It was the emergence of the Goths that helped turn the Crisis of the Third Century into a truly existential emergency in which the Roman Empire nearly collapsed. These Goths would form the Visigoths, who first sacked Rome in 410 AD, and the Ostrogoths, who setup a successor kingdom in Italy following the fall of the Western Empire.

Any discussion of Marcus Julius Philippus must be prefaced by an understanding that the ancient sources are incomplete, fragmentary, and not wholly trustworthy. One of those sketchy details - that he was born in the Roman province of Arabia Petraea (roughly modern Jordan) - was latched onto by later historians, who called him, Philip the Arab (244-249 AD). Like his predecessor Macrinus, Philip faced, as his first important task, the problem of ending a war in the east. He was more fortunate than Macrinus had been; perhaps the army had been convinced by the defeat at Misiche that a peace treaty with the Sassanid king, Shapur, was necessary. Once again Rome paid for peace, and Philip departed for Rome. Alas, he would see little peace throughout his five-year reign. Sometime in the second century AD, peoples who had long lived on the northern peninsulas, which we now know as Scandinavia, crossed the strait in boats and landed on coast of Europe. These newcomers were known to the Romans as the Goths. The sixth-century historian Jordanes, our best source for what happened next, listed a whole array of tribes that fall under the general name of Goth: Screrefennae, Finnaithae, Finns, Dani, Grannii and many more. Accustomed to the frozen north, they were a tough and resilient people. In Europe, they fought their way through the Germanic tribes down towards the Danube, while others made their way over to the east, towards what is not the Ukraine. This divided them into two groups: the Visigoths, or “Goths of the Western Country”; and the Ostrogoths, the eastern half. By Philip's reign, the threat of invasion from the north had become acute enough for the emperor to pay the Goths for an ignominious peace rather than lose an ignominious war. Despite growing instability on the Danube frontier, Romans in the year 248 AD were fascinated by the most momentous event of Philip's reign; the celebrations of the 1,000th anniversary of their city's foundation. According to contemporary accounts, the festivities were magnificent, including spectacular games, in which more than a thousand gladiators were killed, along with exotic animals such as hippos, leopards, giraffes, and rhinoceros. A year later, Philip had fallen behind on his tribute payments, upon which the Visigoths crossed the Lower Danube into Thrace, and ravaged the countryside. In addition to the border unrest, the disgruntled soldiers, still eager for decisive leadership, had placed the purple on the local commander named Marinus; a now increasingly common practice. To restore order, Philip dispatched a new commander, Gaius Decius; a man with senatorial pedigree, who might ease tensions with a Senate increasingly doubtful of the emperor's abilities; and a native of province, who undoubtedly had local connections to exploit. The appointment proved a dangerous blunder. The local soldiers, fearful of punishment and recognising a more appealing candidate for emperor, promptly gave Decius a simple choice; to lead them in rebellion or to die. So Marinus was killed, and Decius named emperor in his stead. Philip marched to meet the approaching Danube legions under Decius, and was bested; the emperor either died in the battle or was murdered in the aftermath.

The victory of Decius (249-251 AD), an established senatorial elite, was one that seemed to reassert the authority of traditional political power, despite the means of his ascension. The new emperor took the honorific Traianus, in reference to Emperor Trajan, whose status as the greatest of all emperors, after Augustus, was now firmly established. He also served as consul in every year of his reign. Decius moreover embarked upon an active building program in Rome - restoring the Colosseum and commissioning the opulent Baths of Decius - something that not really been seen in recent decades. In sum, it seems clear that traditionalism was an important factor in his regime. Another aspect of this conservatism was the "Decian persecution"; the first wide-scale attack on the growing Christian minority. The state required all citizens to sacrifice to the traditional gods, and be in receipt of a certificate from a temple confirming the act; only the Jews were specifically exempted. The new policy was intended most likely as a program to reassert public piety, so the effect on Christianity was to a degree unplanned. Whatever the intention, the new requirements did impact Christians most acutely; a number of prominent Christians did refuse to make a sacrifice and were put to death, including "Pope" Fabian himself. Although the ancient (non-Christian) source all spoke highly of Decius, his brief reign failed to give the Roman Empire the measure of stability it needed. There was a renewed outbreak of the Antonine Plague from about 249-262 AD; traditionally referred to as the "Cyprian Plague", from St. Cyprian of Cathage, who witnessed and described the outbreak. The plague, even on moderate estimates of its death toll, must have seriously hindered the Empire's ability to ward off barbarian incursions, which become more daring and frequent in Decius' time. In the spring of 251 AD, the emperor took the field against the Visigoths. who were besieging the town of Nicopolis, just below the Danube. The Goths fled through the difficult terrain of the Balkans, but then doubled back and surprised the Romans on swampy ground near Abrittus. Decius perished in the battle and his body was never recovered. He was the first Roman emperor to die fighting a foreign enemy; but not the last.

Emperors Valerian and Gallienus (253–268)[]

In 260 AD, Valerian was defeated in battle and taken captive by the Persian king. Later Church writers, who loathed him, gleefully saw this as evidence of divine punishment; that those who oppose the one true God died fitting deaths. However, one innovative idea initiated by Valerian was later used by the emperor Diocletian. Before he moved eastward, Valerian divided the empire in two; he took the east, while his son got the west. By 395 AD, the empire had split into two de facto independent entities; the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Empire.

In 252 AD, the Persian king, Shapur !, took advantage of the internal chaos within the Roman Empire, and launched his next attack against the Syrian border. The Roman legions were hard pressed, defending both the eastern border from Persian pressure, and the northern border from Gothic attacks. The east broke first. Shapur I pushed through the Syrian garrisons, and took most of Syria for himself. In 253 AD, he completed the annexation of Syria, with the capture of its capital city of Antioch. In that same year, Rome finally got an emperor who managed to hold onto the throne for more than a month or two. Valerian (253-260 AD) possessed a high reputation as ex-consul and as general; he was nearly sixty, but for a few years it looked as though he might be able to turn Rome's luck around. The Senate presumably was pleased to ratify one of their own as emperor, and accepted his son, Gallienus (253-268 AD), as co-emperor (Augustus), rather than heir-apparent (Caesar). Valerian apparently recognized the need to share power equally with his son, and to divide their efforts geographically; Gallienus concentrating on the west, and Valerian himself on the east. Gallienus spent most of his time driving back Germanic tribes and fortifying the Rhine-Danube frontier, with some success. In a move characteristic of later diplomacy, he concluded alliances with various Germanic chieftains, to assist the Romans in protecting the frontiers from other tribes. A major escalation occurred in 258 AD, when the Franks broke through the Lower Rhine, and ravaged Gaul; some reached as far as Spain, sacking Tarragona (Tarraco). The Alemanni then invaded and entered Italy, probably due to the vacuum left by the withdrawal of troops against the Franks. Gallienus defeated them near Milan, but was soon faced with the revolts by the governor of Pannonia-Moesia, Ingenuus, and then by the governor of Illyricum, Regalianus; who, like many before and after them, were declared emperor by their troops. By 260 AD, both revolts had been put down, bringing a brief moment of stability. In the east, Valerian's first concern was to the repair the damage caused, not only by the Persian king, but also major Gothic invasions; the Goths had decided to shift their efforts eastward into Anatolia. He succeeded in recovering Antioch and returning the province of Syria to Roman control; at least temporarily. But in 260 AD, his army was ravaged by the plague. When the Persians attacked him at Edessa, he was forced to retreat, and finally to negotiate a peace. Shapur I agreed, as long as the emperor would meet him with only a few guards. When Valerian arrived, he killed his retinue and took him captive. A Roman emperor, still crowned, in captivity to a Persian king and acting as his footstool, was about as humiliating a turnaround as could be imagined. It was certainly a big deal to Shapur, who had carved on his tomb an enormous figure of himself, seated in triumph on horseback; before him kneels a man in Roman dress, asking for grace.

The Crisis of the 3rd Century reached its nadir point in the year 260 AD. The general situation of the Roman Empire was favourable to usurpers. Valerian was a captive, and his son, Gallienus, was now sole emperor, more or less by default. The news shook the Empire, and in the following months, provincials tried to help themselves by choosing their own emperors. One major problem in dealing with these rebellions was the scarcity of manpower; not only was the Roman army scraped thin dealing with invasions from the north and east, but the plague was still wreaking havoc in several provinces. In the east, the remnants of the Roman army proclaimed a fiscal office named Macrianus the Elder as emperor. But Macrianus refused the honour, because of his old age and fragile health; his sons, Macrianus the Younger and Quietus, were elevated in his stead. Their rule won recognition in the eastern provinces from Anatolia to Egypt. Three factors were important for the Macriani revolt: Macrianus senior possessed the treasury that Valerian had brought; Gallienus was far away in the west; and, to people in the east, the isolated attacks of Germanic tribes paled in comparison to the danger to Rome from Sassanid Persia. The two Macriani left Quietus to deal with the Persians, while they marched westwards to face Gallienus in the Balkans. The decisive battle was fought in the spring of 261 AD, most likely in Illyricum. The Macriani were defeated and killed. Quietus then lost control of the east to Odaenathus of Palmyra (d. 267 AD). Odaenathus is a unique individual in Roman history; though technically a Roman citizen, he was consider by most Romans to be a foreign prince. Palmyra was located in an oasis near the edge of the Syrian desert. It had been effectively annexed as a vassal kingdom of Rome by Pompey the Great back in 63 BC, and, since then, greatly prospered by organizing guides and protection for trade caravans. Odaenathus himself was a cunning and resourceful military commander. By 262 AD, he was the only man with the rank, credibility and power to prevent Shapur from permanently conquering the eastern provinces of the Empire. His army fell upon the Persians before they could cross the Euphrates, and inflicted upon them a considerable defeat. He then took the offensive into the Persian heartland. As a vassal king, he was still nominally loyal to Gallienus, but was independent in nearly every other respect. Palmyra would formally secede from Rome after Odaenathus' death in 267 AD, and the ascension of his equally formidable widow Zenobia; the short-lived Palmyrene Empire (270-273 AD). Back in Rome, Gallienus was a competent emperor, but this level of chaos was beyond fixing by any one man. It must have seemed that every commander he entrusted to solve a problem, later used that authority to create another problem. When Gallienus was involved in putting down the Macriani revolt in the Balkans, he put the capable general Postumus (d. 269) in charge of the armies on the Rhine frontier. The direct reason for his rebellion seems to have been a quarrel about booty taken from a barbarian raiding-party destroyed on its way home. While Postumus had distributed the booty to his army, Gallienus' son Saloninus, who had been left behind in Cologne as his representative, ordered him to surrender the booty. In any case, Postumus proclaimed himself emperor, and laid siege to Cologne. Seeing no alternative, the garrison handed over Saloninus, who was put to death. However rather than march on Rome, as every other usurper had done, Postumus vowed to remain in the west, defending it from invasion. By 261 AD, his claim as emperor was recognized by Gaul, Spain, and Britain. He ruled the so-called Gallic Empire (260-274 AD) for the better part of a decade. The central emperor, Gallienus, attempted twice to crush the rebellion, but failed. After 265 AD, he seems to have devoted his attention to the military and political problems on the Danube frontier. Gallienus could see that his days were numbered. He made his enemies eat with him, in an effort to avoid poisoning. He kept around him at all times a small cabal of officers he trusted; all Illyrians (from the western part of the Balkan). But in 268 AD, a few of those very officers killed him.

The ancient writers were not kind to Gallienus and his reign, for obvious reasons; the secession of Odaenathus and Postumus left the Roman Empire shattered into three de facto independent entities. Modern historians tend to see him in a more positive light. After his father's death, Gallienus retained control over Italy, the Balkans, and North Africa for a full eight years, despite numerous revolts and barbarian invasions. This established a strong central authority, that would eventually bring the breakaway provinces back into the Roman fold. In some respects, the division of the Empire actually helped save it from collapse. This left each entity with just one troublesome frontier to focus on: the Rhine River for the western emperor; the Danube for the central emperor; and the border with the Persians for the eastern emperor. Moreover, the military reforms initiated by Gallienus were used by the subsequent string of Illyrian emperors - Claudius Gothicus, Aurelian, Probus, and Diocletian - to end the Crisis of the 3rd Century.

Emperor Claudius Gothicus (268-270 AD)[]

Claudius Gothicus was the first of the "Illyrian Emperors". From the 3st century, Romanised Illyrians and Thracians, mostly belonging to families that had provided career soldiers for generations, came to dominate the Roman army's senior officer echelons. Finally, in 268 AD, the Illyrian officer-class seized control of the state itself, forming a sort of self-perpetuating military junta.

We know almost nothing for certain about Claudius Gothicus (268-270 AD) before he became emperor. He came to be viewed as an ancestor of Constantine the Great, and thus the ancient sources are riddled with fawning praise and outright fabrications. Claudius was an Illyrian, born of peasant stock. Like other low-born provincials, he joined the Roman army probably looking for a better life. He would have entered service in the 230s. Though, for most Romans, these were wretched years, for a common soldier, who showed courage and initiative, they were an opportunity to rise through the ranks. Claudius was fortunate to come into his own during the reign of Gallienus, when granting top military commands to professional soldiers, as opposed to the senatorial class, was increasingly becoming the rule rather than the exception. Gallienus also created a specialist cavalry corp, the Comitatenses, that could be dispatched anywhere in the Empire in short order. One can assume that Claudius had a successful military career, because he became its commander; a role that soon took on the character of the old Praetorian Prefect. The story of Gallienus' deathbed selection of Claudius as his successor is doubtful at best; and very likely an attempt to deflect blame from Claudius' involvement in the assassination plot. Having assume power by way of a coup d'etat, Claudius was quick to distance himself from the murder, and promote the legacy of Gallienus; pressuring a reluctant Senate to deify his predecessor. The first major challenge facing the new emperor was that of the Visigoths, who had assembled a massive invasion force; reportedly 320,000 strong, transported on a fleet of 2,000 ships. After ravaging the southern Black Sea coast, the Goths entered the Aegean Sea, and besieged the port-city of Thessalonica, while detachments attack the islands as far as Crete and Rhodes. At this point, in 269 AD, Claudius designated the future emperor Aurelian as cavalry commander, and left Rome to stop the invasion. At the news of the emperor's advance. their main force retreated over land towards the Danube The resulting Battle of Naissus (269 AD) was one of the great victories in the history of Roman arms. Some 50,000 Goths were allegedly killed or taken captive. There were mopping-up operations on both land and sea, but the Gothic menace had ended; nearly a century would pass before they posed a serious threat again. While the emperor was in the Balkans, the Alemanni broken through the Upper Danube frontier, and crossed the Alps into northern Italy once again. Claudius responded quickly, routing them a few months after Naissus. These victories earned him the honorific Germanicus Maximus, and a golden statue in front of the Temple of Jupiter. There are indications that Spain separated itself from the Gallic Empire of Postumus, and recognized Claudius, at least nominally, as emperor. But he did not live long enough to fulfil his goal of reuniting all the lost territories of the empire. In early 270 AD, he fell victim to the Cyprian Plague and was succeeded by his cavalry commander, Aurelian.

Emperor Aurelian (270-275 AD)[]

Aurelian has almost universally been described as a ruthless emperor with a predisposition to cruelty. His nickname, Manu ad ferrum ("hand on hilt"), implies that he often solved problems with a sword rather than words. Even so, he brought the Empire through a very critical period in its history. and without him it might never have survived.

When Claudius died, his younger brother Quintillus seized power with support of the Senate. With an act typical of the Crisis of the Third Century, the army refused to recognize him, preferring their most senior commanders, Aurelian (270-275 AD). Ancient sources dismiss Quintillus as a mere usurper, who died within three month; either murdered by his own men or by suicide. Aurelian was to be remembered as the restorer of the Roman Empire, bringing the breakaway provinces back into the Roman fold. His first actions were to strengthen his position in his own territories. He quickly set about expelling the last northern barbarians from Roman territory; the Vandals from the Balkans, and the Juthungi from north Italy. His strategy for dealing with the invaders was to order all supplies be drawn inside the major towns and cities, denying them access to food. Then, once the imperial army had forced their surrender. the tribes had to contribute horsemen and soldiers to serve in the Roman army, in exchange for safe-passage home; with Roman manpower sapped by twenty years of war, plague, and famine, new recruits needed to found somewhere. Returning to Rome, in the winter of 271-272 AD, Aurelian ordered the construction of a new system of walls around the city, that became known as the Aurelian Walls; in part still visible today. The cities and towns of the empire had not needed fortifications for many centuries, but now surrounded themselves with thick walls. Aurelian also abandoned the province of Dacia, north of the Danube, as too difficult and expensive to defend. To conceal the shame of ceding Roman territory, he created a new province called Dacia on the safer southern side of the Danube, on the former territory of the province of Moesia.

In 272 AD, Aurelian turned his attention to the lost eastern provinces of the empire, which for 10 years had obeyed the rule of the princes of Palmyra. Odaenathus and his elder son had been assassinated in 267 AD; most sources blame a kinsman. He was succeeded by his underage son Vaballathus, under the regency of his widow Zenobia (d. 274 AD). She must have been a woman of impressive abilities to have been able to assume Odaenathus' authority for herself, as effectively as she did. Initially, Zenobia maintained her late husband's smooth relations with Rome. But in 270 AD, seeing that Rome was too busy with internal strife to notice her, she sent Palmyrene forces into the rich province of Egypt, and claimed it as her own. While the other emperors had failed to notice what Zenobia was doing, Aurelian was a very different kind of ruler. He led his legions east, crossing from Byzantium into Anatolia, and proceeding east toward Syria. He also dispatched a subordinate, possibly the future emperor Probus, to recover Egypt. As he advanced, Aurelian faced little resistance except for the city of Tyana. When Tyana fell, he took no reprisals and marched on. Mercy proved to be very sound policy, because other cities opened their gates to him. Aurelian followed up these peaceful victories with a military ones. He encountered Zenobia and a large army in the vicinity of Antioch; the Battle of Immae (272 AD). Aurelian recognized that the heavily-armed Palmyrene cavalry excelled his own, but won the engagement by feigning retreat and then swinging about once the the heat-baked Palmyrenes were exhausted from the pursuit. His victorious legions advanced south-east, and next encountered the Palmyrene army drawn-up on a flat plain near Emesa, where their heavy cavalry could be deployed. At the Battle of Emesa (272 AD), Aurelian attempted to repeat the same ruse he conducted in Immae, but the Palmyrene cavalry attacked furiously, scattering the Roman cavalry. But, instead of surrounding the Roman army, they broke ranks to pursue the Roman horsemen. The Roman infantry took advantage of the disarray, and wrought great slaughter. Once more Zenobia and the remnants of her army fell back, now to Palmyra. Aurelian followed close behind, besieging the city. In desperation, Zenobia set forth on camel-back to seek aid from the Persians. Aurelian sent horsemen after her; they captured her at the Euphrates. Most of her close advisors were executed, but Zenobia herself was spared to be led in his Triumph of 274 AD; her fate afterward is uncertain. Initially, Aurelian displayed a victor's clemency to the vanquished citizens of Palmyra. But he was obliged to return in 273 AD, when the Palmyrenes revolted under a man named Antiochus. This time, Aurelian allowed his soldiers to sack Palmyra, and the city never recovered. To celebrate these victories, the emperor was granted the honorific Restitutor Orientis ("Restorer of the East").

A silver disc of Sol Invictus ("Unconquered Sun"). Sol, or Helios, was an early Roman deity of minor importance. However, Sol merged with the Eastern sun-god Elagabalus to become Sol Invictus. The cult was first promoted by Emperor Elagabalus without success, but became of supreme importance under Aurelian, until Constantine abandoned Sol in favour of Christianity. Most historians believe that Christmas was set to 25th December, because it was the winter solstice festival of Sol Invictus; his "birthday", so to speak.

In A.D. 274, Aurelian turned towards the breakaway Gallic Empire, which at this time controlled Gaul and Britain. After Postumus' assassination in 269 AD, it had become beset by internal conspiracies and Germanic invasions. The latest "Gallic emperor", Tetricus, seems to have conspired with Aurelian to abandon his throne, and allow the provinces to return to the Roman fold. When the two sides met at the Battle of Châlons (274), Tetricus simply deserted to the Roman camp, and his soldiers, left to fend for themselves, were easily defeated. The emperor rewarded Tetricus for his collusion, making him a Senator and an administrator of a town in southern Italy; he died of natural causes several years. More honorific came the Aurelian's way; he was called Restitutor Orbis ("Restorer of the World"). The emperor initiated many necessary reforms to consolidate the reunited Roman Empire. The fragility of his predecessors’ position had accelerated the effects of economic troubles, and particularly the major ill of the century, inflation. Its sources and extent are complex and still disputed, but, in part, it derived from an official debasement of the Roman coinage. As each of the short-lived emperors took power, they needed to raise money quickly to pay the army's bonus, and the easiest way was to debase the silver purity of the Roman denarius. By the time Aurelian came to power, people were losing faith in the Roman coinage. Aurelian tried to curb the freefall by issuing a better quality denarius containing 5% silver. Twenty such coins would contain the same silver as an old silver denarius; considering that this was an improvement over the previous situation gives an idea of the severity of the problem. But he struggled to introduce enough "good" coins and recall all the "bad" coins, so met with only limited success. Monetary reform would continue under emperors Diocletian and Constantine, but the problem was only truly solved until Byzantine times, by Emperor Anastasius (d. 518 AD). Aurelian also promoted the cult of Sol Invictus ("'God of the Unconquered Sun"); the eastern sun-god Elagabalus incorporated into the Roman pantheon. The centre of the cult was a magnificent temple, built on the Campus Martius, with the spoils of Palmyra. His intention was to give to all the peoples of the Empire, civilian or soldiers, easterners or westerners, a single god they could believe in without betraying their own gods; and so create a kind of religious unity. This principle of "one faith, one empire" would come to fruition under Constantine. In 275 AD, Aurelian was planning a major campaign against Sassanian Persia, hoping to take advantage of the death of Shapur I. Before he could do so, however, he was murdered in a conspiracy planned by his secretary. The secretary's motives seem to have been personal; he felt threatened by the emperor's severe punishments for corrupt officials.

Emperors Tacitus to Carinus (275-284 AD)[]

Coins of the six successors of Aurelian. Clockwise from right: Tacitus, Florianus, Probus, Carus, Carinus, and Numerian

The emperors were now leaning heavily on the army for legitimacy, but Rome had too many armies, on too many frontiers, for this to be anything like stability. In the nine years after Aurelian, six men were given the title of emperor, and each one was murdered. The possible exception to this was the fourth, Carus (282-283 AD). His men claimed that he had been struck by lightning while camping on the banks of the Tigris. This was just barely plausible. On the other hand, when Carus was “struck by lightning”, the commander of the imperial cavalry, Diocletian, was in the camp. Carus’s two sons then became co-emperors; Carinus (283-285 AD) in the west, and Numerian (283-284 AD) in the east. Numerian is best known for the bizarre manner of his death. He was riding in a closed litter because of an inflammation of the eyes, and, when he died, no one noticed until the distinctive odour of decay began to issue from the litter. In all likelihood, the man had succumbed to illness, and his senior officers were keeping the matter quiet until the loyalty of the army could be tested. The premature discovery of the body led to a military assembly in which Diocletian accused the Praetorian Prefect of having a hand in Numerian's death. Diocletian then vindicated his claim by running him through with his sword. The army took the hint and proclaimed Diocletian emperor. He then met and defeated Carinus at the Battle of the Margus (285 AD), near Belgrade. The story of Carinus being deserted and murdered by his own men is consistent with the hostile propaganda of his victorious opponent. This left Diocletian at the head of the entire Roman Empire.

Emperor Diocletian (284-305 AD)[]

Diocletian had an administrator’s genius rather than a soldier’s. Without being especially innovative, he had an excellent grasp of organization, a love of order, and great skill in picking and trusting men to whom he could delegate. His reign is considered the beginning of the second phase of the Roman Empire, a more overtly despotic and militaristic phase known as the "Dominate". Partially Diocletian failed in his task; without his guiding hand, the empire fell into civil wars. Constantine's reign, however, demonstrated the benefits of Diocletian's transformation of imperial government; the frontiers remained secure despite the civil war; the autocratic principle and bureaucratic infrastructure remained; and if anything, Constantine took Diocletian's court ritual to even great heights.