| Greek Foundation of Classical Antiquity | |

| Period | Classical Antiquity |

| Dates | 539-371 BC |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by Cradles of Civilisation |

Followed by Age of Alexander |

| “ | The unexamined life is not worth living. | ” |

–Socrates | ||

The Greek Foundation of Classical Antiquity lasted from about 539 BC until 371 BC. It began with the rise of the greatest of all the ancient empires yet seen, that of Achaemenid Persia, whose long struggle with Ancient Greek would become legendary. It then ended with the disastrous Peloponnesian War, which was to break the back of classical Greece, and pave the way for the rise of Macedonia.

The role of the Greeks was pre-eminent in making the "Classical" world, and with them its story must begin. Around 800 BC, the Aegean had begun to settle into a new social and political structure; a loose collection of city-states united only by a shared language and culture. By the standards of its contemporaries, early Greece was a rapidly changing society: population pressure spurred a great age of Greek colonization; growing prosperity prompted a new style of warfare, Hoplite citizen-soldiers, who were to be for centuries the backbone of Greek armies; and class struggles transformed hereditary kings supported by aristocracies into various forms of collective rule, including nascent democracies. Athens and Sparta were to quarrel fatally in the fifth-century, and this has led them to be seen as the poles of the political world of Ancient Greece. They were not, of course, the only models available. Herein lies one of the secrets of the Greek achievement. It could draw upon a rich variety of political experience, providing the data for the first systematic reflections upon the great problems of government, law, duty, and obligation, which have exercised men’s minds ever since.

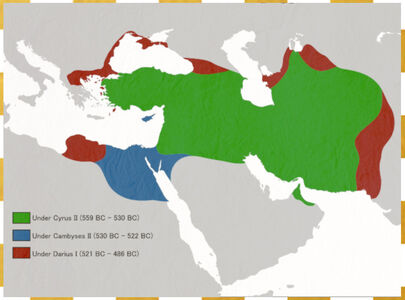

The Greek struggle with Persia was the climax of the early history of Greece, and the inauguration of its Classical Age. Because later Greeks made so much of this long conflict, it is easy to lose sight of the many thing they had once found to admire. Cyrus the Great founded the largest empire the world had seen until that time, spanning three continents; Europe, Asia and Africa. It is best known for merging Persian, Iranian, Lydian, Babylonian, Israelite, Egyptian, Indian, and Greek cultures relatively harmoniously; for freeing the Jews from their "Babylonian captivity"; for its successful model of a centralized administration; for building infrastructure such as roads and postal systems; and for developing one of the first large, professional standing armies. Because of its long endurance, Persia influenced the language, religion, architecture, philosophy, law, and government structure of all future Near Eastern empires.

The passage from the Greek glorious days of victory over Persia, to the Persians' almost effortless recouping of their losses thanks to Greek division in the Peloponnesian Wars, is a historical drama which grips the imagination; was a real opportunity to unite Greece squandered after Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis? But the fundamental reason why such intense interest has been given to these few centuries lies in the extraordinary cultural legacy of Classical Greece; it is an achievement of the mind that constitutes their major claim on our attention. Every schoolboy used to know the names of Homer, Pythagoras, Euclid, Archimedes, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. In the end, the Greeks are remembered as poets and philosophers, and their views - on politics, sculpture, architecture, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, history, and literature - were to dominate both Europe and the Islamic world until the sixteenth century.

History[]

Emergence of Greek City-States[]

In the early eighth century BC, Greece began to emerge from the dark ages, which had hidden events and processes since the Bronze Age Collapse. There is even a date or two, one of which was important in the development of Greek self-consciousness. In 776 BC, it is said, the first Olympic Games were held; a religious festival, held at the temple of Zeus in the city of Olympia. Later Greeks would count from that year as we now count from the birth of Christ. The people who gathered for that first festival games recognized by doing so that they shared a culture. Its basis was, first and foremost, a common language; whether descended from Mycenaeans or Dorians, they all spoke Greek. The great festival games were occasions to which only Greek-speakers were admitted; a language that now acquired the definition which comes from being written down, using an adaptation of Phoenician script. Important to the understanding of this period is the powerful belief in the Greeks as three distinct clusters. The old Mycenaean cities had buckled, three hundred years earlier, in the face of the "Dorian invasion", but survived on the peninsula known as Attica (the land around Athens). Other Mycenaeans, driven from their homeland, had sailed across the Aegean See over to the coast of Anatolia (the major part of modern Turkey), where the mixture of Greek and Near Eastern ways resulted in a distinctive culture which we call Ionian. Meanwhile, the Dorians had established their own strongholds down on the Peloponnesian peninsula. All three groups then spread across the nearby islands. The Doric dialect was distinct from the Mycenaean dialect, and both were different from the Ionian version. As the Dorian disruption receded into distant memory, the Greek peninsula entered into a period of relative peace, in which the Greeks were more likely to act as allies than enemies. Sometime around 800 BC, this growing sense of a common cultural identity led to the weaving together of a mass of different oral traditions (mainly Mycenaean) into two related epic poems, which would soon be claimed as the heritage of all Greeks: the Iliad and the Odyssey. Later Greeks attributed these masterpieces to one Ionian poet, Homer. Much time and ink have been spent on arguments about who he was (or wasn't); theories range from a single genius to a whole school of poets writing under a single pen-name. For our purpose, the important point is that the stories of the Siege of Troy, and the heroes who fought there, offered the Mycenaeans and Dorians and Ionians a mythical shared past. In the Iliad, for the first time, we come across a word for those who lived outside Greece. Homer calls them barbaro-phonoi (“strange speakers.”) or barbarians; though the word was less dismissive than it is in modern usage. It was a simple division of all peoples into two; human nature was either Greek or non-Greek. The other foundation of Greek identity was religion. Perhaps Homer did as much as anyone to order the enormously complex Greek pantheon, an amalgam of myths from many communities over a wide area; some of them imported from the Near East and Egypt. It is a religious system very different from that of other civilisations in its ultimately humanizing tendency. The Greek gods and goddesses, for all their supernatural power, behaved in postures all too human, and showed very human vices. The Iliad and Odyssey present the gods trying to outdo one another; Poseidon harries the hero Odysseus on his way home, while Athena takes his side, A later Greek philosopher grumbled that Homer "attributed to the gods everything that is disgraceful and blameworthy among men: theft, adultery and deceit". Human though Homer’s gods might be, the Greeks also had a deep respect for the occult and mysterious, especially oracles. The most famous of these by far was the oracles of Apollo at Delphi (though there were many others), the sources of respected, if enigmatic, advice. Together with language, a shared heritage of religion and myth was the most important constituent of being Greek, always and supremely a matter of common Hellenic culture. They belonged, they felt more and more,, to "Hellas". It may surprise you, but the Greeks did not call themselves "Greeks"; that name was given them centuries later by the Romans. The word they would have used was Hellenes; which derives from Hellen, the mythological ancestor of all true Greeks.

The strength of Greek identity was never politically effective. It is in the geographical setting of Greek history - which was not what we now call Greece, but rather the whole Aegean - that much of the explanation must be sought. For the most part, agriculture was confined to narrow strips of land, framed by rocky mountains, forested hills, or the sea. This made possible a cluster of economically viable cities, and communication between them was usually difficult. Consequently, the Greek cities were independent city-states that tended to look outwards to the sea; none of them, after all, lived more than forty miles from it. This inclination was intensified, in the eighth century BC, by population pressure; perhaps growing as much as threefold between 800 and 700 BC. These people needed more grain, more metals, and especially more land. Land was traditionally divided between all of the sons, meaning that any family’s holdings shrank inexorably over time. Ultimately, this led to a great age of colonization. Around 775 BC or so, the Greek cities of Chalcis and Eretria sent a joint expedition to build a colony at Pithecusae (the isle of Ischia), on a little body of water known today as the Bay of Naples. Around 740 BC, these same two cities began to force-out all of their younger sons as colonists, founding no fewer than five cities (Cumae, Naxus, Lentini, Catana, and Rhegium) over the next twenty years. Not to be outdone, around 733 BC, the city of Corinth put an aristocrat named Archias at the head of an expedition to Sicily, where he founded a colony called Syracuse. The setters who ventured out to these new Greek cities had to give-up their citizenship in their own “mother city”, the home city from which they came. Their entire identity as Greeks now rested on their ability to establish a Greek enclave in foreign lands; they planted Greek grain, ate Greek food, built Greek temples, told Greek tales, and sent their delegations to the Greek games. By the end of the colonization period, probably around 630 BC, the Greek world stretched far beyond the Aegean; Massalia (modern-day Marseille), in the west, became the base for a series of further colonies as far away as Spain; in the east, as many as seventy colonies were planted around the Black Sea, among the Byzantium; and a few colonies were even founded on the Libya, to the south. Some Greek colonies seem to be where they are because of their farming potential; some because of trade; and others to access metals they could not find in Greece. Nor were colonists the only agents diffusing Greek ways; and teaching Greece about the outside world. From the sixth century onwards, a considerable number of Greek mercenaries could be found in the service of foreign kings. Historical records show us that, when the Persians took Egypt in 525 BC, Greeks fought on both side. Some of these men must have returned to the Aegean, bringing with them new ideas and impressions. By then, a process of cultural interplay was working both ways, for Greece was both pupil and teacher. The Lydians of western Anatolia, for example, kingdom of the legendary Midas (who turned everything he touched into gold), were Hellenized by contact with the Ionian Greeks; they took its art from them, and, perhaps more importantly, its alphabet. All these developments were to have important social and political repercussions on the Greek homeland.

Each hoplite, the famous Greek citizen-soldier, provided his own equipment. He typically wore bronze armour (helmet, body-armour, and greaves), and carried a round shield. His main weapon was the spear, which he did not throw, but thrust and stabbed in the mêlée which followed a charge by an ordered formation (the Greek phalanx) whose weight gave it effect. They depended completely on their power to act as a disciplined unit, because each hoplite was protected partly by the shield of his neighbour on his right-hand side. The Spartans were particularly admired for keeping an ordered line in the preliminary charge, and for retaining cohesion once the scrimmage had begun.

By the standards of its contemporaries, early Greek civilization was a rapidly changing society. One important development, towards the end of the seventh century, was an upsurge of trade with the non-Greek world. Part of the evidence is an increased circulation of silver. The Lydians had been the first to strike true coins - tokens of standard weight and imprint - around 650 BC. It was quickly adopted by Greek communities, spreading as far west as Sicily before 525 BC; only Sparta resisted its introduction. Commerce became a possible answer to land shortage at home. Athens assured the foreign grain she needed by specializing in the output of great quantities of pottery and olive oil; Chois became known for high quality wine. All this new commercial wealth began a revolution, both military and political. The old Greek ideal of warfare had been a military aristocracy, few in number and preoccupied with personal courage, riding to the field of battle to confront their equals, while their less well-armed inferiors brawled about them. The new commercial class could afford the armour and arms which provided a more effective approach; "hoplites", the regiments of heavy-armed infantrymen who were to be the backbone of Greek armies for two centuries. They would prevail by disciplined cohesion, rather than by individual derring-do. This implied some sort of regular training, as well as a social widening of the warrior class. As more men came to share in the power which comes from exercising military force, they battered away at the existing élites to get admission to political power. It was in these years that the Greeks invented politics; the notion of making collective decisions by debate in a public setting. The magnitude of what they did lives on in the language we still use, for the word "politics" derived from the Greek word for city, polis. By the beginning of historical times, most Greek cities seem to have been dominated by small groups of aristocratic families, who had already supplanted the kings themselves. Inevitably, they tended to be self-serving and corrupt. In Hesiod's poem Works and Days, composed sometime in the mid-eighth century BC, he longs for a day when men will benefit from their own labour, rather than seeing it stolen by the more powerful. The new men sought to replace these aristocratic oligarchies with governments less respectful of traditional interests; the result was an age of what the Greeks called "tyrants". The earliest example was Cypselus, who seized power in Corinth in a coup in 655 BC; he was followed by a series of others throughout the peninsula. The later sinister connotations of the word tyrant did not then exist; they were not necessarily cruel, though they tended to be autocratic in order to keep power. They brought peace to social struggles largely arising from limited land. This phenomenon did not last; few tyrannies lasted into a second generations. In the sixth century, the current turned towards collective government; oligarchies, constitutional governments, even nascent democracies began to emerge almost everywhere. It is risky to generalize about such matters. There were more than a hundred-and-fifty Greek cities, and about many of them we know nothing; of the rest, we know only a little. The detail of what went on can only judge by the two cities we know most about; Sparta and Athens.

Spartan helmet on display at the British Museum. The helmet has been damaged with the top having sustained a blow, presumably from battle.

The city of Sparta, in the centre of the Peloponnese, took a different approach to the problem of population growth. They were Dorians who had settled on Mycenaean ruins, and built a city of their own on the Eurotas river. The river was useful as a water supply, but shallow, rocky, and unnavigable; so the Spartans had no ships. While other Greek cities were sending out boatloads of colonists, the Spartans armed themselves, crossed over the mountain range to the west, and conquered the neighbouring city of Messenia. It was not an easy conquest; the Spartan poet Tyrtaeus says that the war lasted twenty years. But by 630 BC, Messenia had become a subject city, and Sparta was more than a city; it was a little kingdom. In this Spartan kingdom, the conquered Messenians become a whole class of slaves (helots), who grew all the food for their masters on terms as harsh as anything found in ancient times. The Spartans themselves became the aristocracy, a master race of warrior men and mothers of warriors. There was no risk of a new commercial class developing, for there is no commerce; even coins were prohibited until the third century BC. Sparta had one peculiarity not found anywhere else in the ancient world; two kings. descendants of the legendary twin brothers who had founded Sparta. Even with two kings playing tug-of-war with power, the Spartans kept on shoring themselves up against unchallenged monarchy. According to Aristotelian political theory, any form of government holds three primary powers: the military power to declare war; the judicial power to make and enforce laws; and the religious power to maintain good relationships with the gods. In Sparta, the kings held all three powers; but with limitations. They had the unilateral right to declare war, but one king must lead the army, be the first into the charge, and the last to retreat; which no doubt kept them from fighting needless wars. The judicial power for the kings gradually shrank, until, by the fifth century BC, almost all lawmaking fell to a council of twenty-eight elders (the ephors). And finally, the kings were high priests responsible, in partucular, for maintaining communication with the oracle of Delphi, but up to four ephors must accompany them to hear her pronouncements; omens exercised great authority in Sparta. There was also a Spartan public assembly of all male citizens over thirty, called the Ekklesia, but its power was limited to electing member to the ephors. Even there, Spartans were not permitted to debate; the airing of views was not considered useful. But the real power in Sparta was neither the kings, nor the council of Ephors. The Spartan state was ruled by a strict and unwritten code of laws that governed every aspect of life. Our knowledge of them comes mostly from Plutarch (d. 119 BC), writing centuries later. Even allowing for distortion, these laws have long fascinated and bemused. Children did not belong to their families, but to the state; the Ephors had the right to inspected each newborn, giving it permission to live, or else to die on the “place of exposure”, a wasteland in the mountains. At the age of seven, boys were assigned to the Agoge, learning to fight, to forage for food, and cultivating ready obedience. Girls too, who were the future Spartan mothers, seem to have gone through a fairly rigorous education, with more emphasis on music, dancing, singing and poetry. In this respect, Sparta was unique; in no other Greek city did girls receive any formal education at all. Adult Spartan men did not live with their families, but the communal dormitories and ate meals in common "messes". In order to prevent greed and envy, they avoided dressing differently, and were not supposed to own silver or gold. Their condition of life was, in a word, "spartan", reflecting a sort of militarized egalitarianism often admired by later puritans. These laws were unwritten. The semi-mythical Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus explains, "Laws only work if they are written on the character and heart of the citizen"; the Spartans themselves continually watched each other for violations. Generations later, one Spartan king tried to explain to Persian king Xerxes how this had affected the Spartan character; "Although they’re free, they’re not entirely free. Their master is the law, and they’re far more afraid of that than your men are of you". Yet a cloud hung over Sparta, and it was remarked by other Greeks; the fear of a Helot revolt. It hobbled Spartan ambition. Increasingly, they feared to have their army far from home. Sparta was always on the alert and the enemy was at home.

The Acropolis of Athens by Leo von Klenze (1846). The leading position of Athens may well have resulted from its secure stronghold on the Acropolis, its central location in the Greek world, and its access to the sea.

To the north, across the land-bridge that connected the Peloponnese to the rest of Greece, Athens had gone one further than Sparta by getting rid of its kings altogether. In very ancient times, the city had been ruled by the mythological Theseus, whose palace stood on the Acropolis. During the dark ages, many of its inhabitant had wandered east to become part of the Ionian settlements along the Anatolian coast. But some remained to keep the city alive. The happenings in the years before 650 BC are preserved only in fragmentary accounts written centuries later. Pieced together, they show a slow and crooked path away from monarchy towards a sort of aristocratic oligarchy. By the beginning of historical times, the role of Athenian king had been renamed: it still passed from father to son, still lasted a lifetime, but it was now called an archon, or chief justice. Another official, the polemarch, was given control of the military, while a third carried out priestly functions. Thirteen archons later, these offices were filled from the wealthier landowning class by election every ten years; after 683 BC, the offices were held for only a single year. They were elected by an assembly of ex-archons (the Areiopagos), other wealthy landowners; which also served as a council advising the archons. Like Sparta, Athens had grown to be something larger than a city, bringing the other towns of the tiny Attica peninsula under its control. This process, which seems to have happened more or less peacefully, created the largest and wealthiest state on the Greek mainland. But it also created a larger class of people excluded from political life. In 632 BC, a would-be "tyrant" named Cylon attempted to seize power in Athens. However, the coup was opposed by the people of Athens; Cylon himself escaped, but his followers were besieged in Athena's temple on the Acropolis. They were persuaded by the archons to leave the temple and stand trial, after being assured that their lives would be spared. But when the conspirators began to stagger out, the archons murdered them anyway; a dreadful sacrilege, since the men had been promised protection at the goddess's temple. For this crime, the archons were all exiled from the city. But the unrest that followed showed that Athens was not at peace under its oligarchic system. In response, the Athenians did what the Spartans had refused to do: to set-down the law in writing. The man who took on the job was an elected archon named Draco (d. 600 BC). His law code was remarkable not for what it outlawed (murder, theft, adultery), but for the penalty of death which was attached to so many crimes. However, these "Draconian" laws ultimately failed to quell the conflict between rich and poor. In 594 BC, another archon named Solon (d. 560 BC) made a second stab at a fair law code. His first reforms dealt with relief for impoverished peasants. Not only did the aristocratic families hold nearly all political power, they own most of the land. Meanwhile, the free smallholders were increasingly falling into debt in tough years. If they mortgaged their land, a pillar was conspicuously placed upon it. The farmer must then pay a sixth of all his produce to his creditor; if he defaulted on his payments, he would be enslaved. Solon boldly removed all the pillars (thereby cancelling their debts), and, at the same time, made it illegal for anyone to be enslaved by a creditor. Having eased the burden of the poor, he attempted to open-up the political structures of Athens. Under his reforms, a new popular assembly (the Ekklesia), which was open to every male citizens, assumed the role of electing the archons; which was not quite as democratic as it sounds, since to be a citizen, a man must own land. These archons were assisted by a new advisory-body of four-hundred (the boule). The old Areopagus, which formerly had these roles, remained but now became only a law court for certain matters. All this didn't please the rich. Nor did it please the poor, who had hoped for more; not just debt cancellation, but land redistribution. Solon's moderate reforms pointed clearly to the future, but did not at once legislate Athens to peace.

Cleisthenes is regarded as the "Father of Athenian Democracy". His reforms gave all the male citizens, regardless of wealth, a voice in political decisions. Athenian democracy would provide the stability necessary to make Athens the cultural and intellectual center of the ancient world.

After Solon, the Athenians divided into three squabbling factions, each with its own nickname; the Men of the Coast, the smallholders who supported his reforms; the Men of the Plain, the old aristocratic families who wanted all power back in their own hands; and the Men of the Hills, the landless poor who wanted the same privileges as everyone else. This third group was the wildest, and their leader, Peisistratus (d. 527 BC), proved the most ruthless. In 560 BC, he launched a coup, and seized power in Athens. Although he lost and regained power twice, Peisistratus ruled as a "tyrant" for thirty years of relative peace and prosperity. He did not hesitate to confront the aristocracy, confiscating their lands and giving them to the landless. He also promoted Athens as a cultural centre (in part to enhanced his own prestige); new festivals were inaugurated such as the Panathenaic Games honouring Athena (who now became patron goddess of the city), as well as the Dionysia honouring Dionysus, the god of wine and pleasure. On his death, Peisistratus was even succeeded by his eldest son Hippias, in quite king-like fashion. This did not cause any great heartburning, until a family crisis ensued. Hippias' younger brother was murdered in a private squabble with a former lover named Harmodius. Although Harmodius was killed on the spot, his accomplice Aristogeiton was duly arrested. An enraged Hippias had the young man tortured for an unspeakably long time, until Aristogeiton, maddened by pain, accused all sorts of Athenians of plotting to seize power. Hippias then began a purge of everyone named, and anyone else who got in his way. The Athenians were delivered from this mess by an unlikely saviour; the Spartan king. This king, Cleomenes (d. 590 BC). marched on the city not out of love, but out of fear; Athens was now the biggest barrier left between Sparta and the advancing Persian juggernaut, so could not be allowed to fall into anarchy. This intervention by the Spartans only served to hasten the progress towards democracy. With the tyrant ousted, it took some time for the Athenians to settle affairs with the various factions. When the dust settled in 510 BC, an aristocrat Cleisthenes (d. 508 BC) was appointed by popular support to reform the formerly tyrant-dominated government. Under Cleisthenes, at last, began to operated the fully fledged Athenian democracy. The popular assembly (the Ecclesia) became the de jure mechanism of government; it had the final say on legislation, and the right to call officials to account after their term of office. But his boldest reform was a restructuring of Athenian political loyalties. Until now, every Athenian citizen was a member of one of four long-established tribes, based on links of kinship. Inevitably, aristocratic families wielded great influence within them. To break-up these highborn power networks, Cleisthenes replaced the tribes with ten abstract units of electoral democracy; Attica, the territory of the Athenians, was divided into three regions - the city itself, the coastal plain, and the inland hills; each of these was subdivided into ten smaller regions called demes, making thirty in all; and each electoral unit consisted of one demes from the city, one from the plain, and one from the hills, in order to prevent the emergence of sectional factions - city-dwellers against country-folk, farmers against merchants. This was a coldly rational idea; the astonishing thing is that it worked. The ten new "tribes" soon become the heart of political life. A new custom was also introduced at this time; "ostracism". Any citizen of Athens could be exiled from the city for ten years, should a plurality of his compatriots write his name on pieces of pottery (called ostraka) which were used as ballots. The initial trend was to vote for a citizen deemed a threat to democracy; a would-be tyrant. But soon anyone judged to have too much power in the city tended to be targeted for ostracism; “Ostracism was not a means of punishing a crime," Plutarch remarks, "but a way of relieving and assuaging envy ... an emotion which finds its pleasure in humbling outstanding men”. Nonetheless, Athenian democracy would provide the stability necessary to make Athens the cultural and intellectual centre of the Greek world.

Sparta and Athens were to quarrel fatally in the fifth century BC, and this has led them to be seen always as the political poles of the Greek world. They were not, of course, the only models available. And herein lies one of the secrets of Greek achievement. It could draw upon a richness of political experience far greater than anything seen in the world until this time. This provided the data for the first systematic reflections upon the great problems of government, law, duty, and obligation, which have exercised men’s minds ever since. The Greek world had frontiers where conflict was likely. In the west, they once seemed to be pushing ahead in an almost limitless expansion, but this came to an end around 550 BC, when the Carthaginians and Etruscans prescribed that limit. In the east, the Greek cities on the Anatolian coast had often been at loggerheads with their neighbours. They suffered much against the Lydians, until they came to terms with Croesus of legendary wealth, and paid him tribute. Nonetheess, an even more formidable opponent loomed even further east; Persia.

Rise of Persia[]

The Holy Fire at the Zoroastrian Temple of Yazd in Iran. Of its spiritual founder, Zoroaster, we know almost nothing except his achievement, and that he was believed to have experienced divine revelations. There is no consensus even on when Zoroaster lived and taught. While most scholar consider a date around 1000 BC to be the most likely, dates between 1500 BC and 500 BC have also been proposed.

The starting-point of Ancient Persia is, once again, a great migration. On the high plateau, which is the heart of modern Iran, there were settlements in the fifth century BC; the city of Susa, which would later become part of Elam, was founded around 4400 BC. But the word "Iran" in its oldest form means "land of the Aryans", These wandering peoples are thought to have arrived in the region at some point in the second century BC. In Iran, as in India, the impact of the Aryans was to prove ineffaceable and founded a long-enduring tradition. They brought with them a polytheistic religion - closely related to the Vedic belief system of India - in which many gods were presided over by a chief deity, Ahura Mazda (god of wisdom). At some point before 1000 BC, the priest-turned-prophet Zoroaster claimed divine revelation, and conceived of a religion that has been called monotheism; Zoroastrianism. He taught his disciples that there was only one true god, Ahura Mazda; the other gods, such as Mithra (god of justice) and Anahita (goddess of fertility), were demoted to "emanations" of Ahura Mazda. The presence of evil in the world, according to Zoroaster, reflected as an eternal struggle between Ahura Mazda, and an equally powerful opposing force, Angra Mainyu; good and evil, light and darkness, truth and deceit. He rejected all but one ritual practiced by the Aryans, keeping only the veneration of fire; so the holy fire became, in Zoroastrianism, the symbol of the divine. It is not known how rapidly or widely this creed spread through Iran, but it was eventually adopted as the official religion of the various Persian empires. It would influence not only Judaism but Christianity and Island; the notions of angels and demons, and heaven and hell, both came from Zoroaster.

The Ancient Iranians (as we may now call them) were made up of many tribes, of which two - especially vigorous and powerful - have been remembered by their Biblical names as the Medes and the Persians. It was at first the Medes (728-549 BC) who play the dominant role. They populated the region of north-west Iran, where they were often at loggerheads with their powerful western neighbours, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Sometime around 728 BC, the Median tribe managed to coalesce into a kingdom. According to tradition, a clan judge named Deioces gained a reputation for fairness and integrity that spread among the other clans, until they proclaimed him leader of them all. Considered the first king and lawgiver in Iranian history, Deioces (728-678) is credited with founding the city of Ecbatana as his capital; one of the most startling cities of ancient times. It was built on the eastern slopes of Mount Orontes, and surrounded by seven concentric walls, each painted with bright colours; the outer wall white, the next black, the next scarlet, the next blue, and then orange; and the last two walls were gilded respectively with silver and gold. Deioces was succeeded by his son Phraortes (675–653 BC), who built on his father's achievement. He subjugated the nearby Persians, who had established themselves in the old lands of Elam (now south-western Iran). Phraortes then set his sights on the strife-riven Assyrian Empire, which had dominated the Near East for so long. This proved a miscalculation. The Assyrians had secure their northern border by alliance with a nomadic tribal confederation on the Pontic steppe, north of the Black Sea. These Scythians poured down into western Iran from the Caucasus Mountains; the first major eruption a new force in world history, nomads straight out of Central Asia, fighting with the bow from horseback. Not only were the Medes defeated, but Phraortes himself was killed, and both Medes and Persia came under Scythian dominance. Some twenty-eight years later, a son of the dead Phraortes named Cyarxes (d. 585 BC) led a revolt. According to Herodotus, he invited the Scythian court to a banquet on his estate, got them thoroughly drunk, and then had them all killed. At once, Cyarxes reorganized the army in preparation for war; whereas the Medes had fought as militias divided into tribal clan, he instituted a regular army organised by speciality (foot soldiers, archers, and cavalry). All around him lay nothing but chaos; to the north, the disorganized and leaderless Scythians, and to the west, a dying Neo-Assyrian Empire. Cyarxes knew an opportunity when he saw one, and offered his friendship to Neo-Babylonian king Nabopolassar, who accepted. They agreed to push Assyria over the edge, and divided its territory between them; an agreement sealed by the marriage of Cyarxes' daughter to the Babylonian crown prince, Nebuchadnezzar II, eldest son of Nabopolassar. In 612 BC, the newfound alliance sacked and destroyed Nineveh, bringing an abrupt end to the story of Assyria. While the Babylonians became heirs to all of the Assyrian holdings within Mesopotamia, the Medes share of the spoils were the eastern and northern highland. By the time Jerusalem fell to Nebuchadnezzar in 587 BC, his father-in-law Cyarxes had became embroiled in war with the Lydians, the dominant political power in western Anatolia. For three years, the two armies faced each other across the Halys River, neither able to gain an advantage. Cyarxes had now been king of the Medes and Persians for forty years; he was old, ill, and ready to stop fighting; sealed by another diplomatic marriage between Cyarxes' son Astyages, and a Lydian princess. He died not long after, and Astyages (d. 585 BC) succeeded on the Median throne. Comparatively little is known of his reign, except that he was dethroned by his grandson Cyrus, known to history as Cyrus the Great, founder of the first Persian empire. The ancient sources may be called legend, rather than history. According to the best known account by the Greek historian Herodotus, Cyarxes, king of the Medes and overlord of the Persians, had a prophetic dream, in which a vine grew out of his daughter Mandane's womb and curled itself around his entire kingdom. Fearing the dream, he married her off to a subordinate man; the vassal Persian prince Cambyses (d. 559 BC). The couple soon had a son, Cyrus. When a second dream warned Cyarxes of Mandane's offspring, he sent his chief general Harpagus to kill the infant. However, Harpagus, unwilling to spill royal blood, gave the baby to a shepherd to raise instead. Years later, the inevitable happened; ten-year old Cyrus was discovered play-acting the role of king with the other boys of his village. Astyages was pursuaded to spare the boy, returning him to his parents. Harpagus, however, did not escape punishment; Astyages had the boy murdered; Astyages is said to have fed him his own son at a banquet. This story is clearly a reprisal of the ancient Sargon-Moses trope; a baby in peril, miraculously saved, destined for greatness.

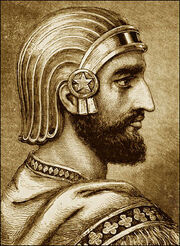

An artistic portrait of Cyrus the Great, based on a relief found on a doorway pillar at Pasargadae, on top of which was inscribed in three languages the sentence, "I am Cyrus the king, an Achaemenian". British historian Charles Freeman suggests that "In scope and extent his achievements, Cyrus ranked far above that of the Macedonian king, Alexander, who was to demolish the his empire in the 320s BC, but fail to provide any stable alternative".

By his own account, generally believed, Cyrus the Great (550–530 BC) was born to the Persian prince Cambyses and the Median princess Mandane. He grew-up the city of Pasargadae (in the modern Iranian province of Fars, on the edge of the Persian Gult), surrounded by his father's family, the Achaemenids; the largest and most powerful of the Persian clans. Upon succeeding his father in 559 BC, Cyrus began planning a revolt against Astyages, his maternal-grandfather. The other Persian clans, who had chafed under Median rule for a century, willingly join him. When Astyages heard of Cyrus's revolt, he ordered his own army to march against the rebels, headed by his chief general Harpagus; who, in Herodotus' account, had long hungered to avenge the "abominable supper". In the first battle, Harpagus defected over to Cyrus' side, along with several other noblemen and a portion of the army. Despite Harpagus' betrayal, the Medes met the rebels in a second battle, led by Astyages personally, but were defeated; the king was taken prisoner, and Cyrus took control of Ecbatana in 550 BC. He spared life of Astyages, and married his daughter to consolidate his power over Medes. This was merely the start of his conquests. The Lydians of western Anatolia were now ruled by Croesus, who had subjugated all of mainland Ionia Greek cities. The lucrative trade carried-out by them across the western Mediterranean had brought him as much wealth as his legendary predecessor Midas, two hundred years earlier. In a likely legend recounted by Herodotus, it was Croesus himself who provoked the war with Cyrus. When his brother-in-law Astyages was overthrown, he consulted the oracle of Delphi, who told him that, if he went to war with Persia, he would "destroy a great empire"; but not which one. The two side met at the Halys River, and fought to a stalemate. Croesus drew back, intending to appeal to his allies for aid, but Cyrus followed too quickly. Before the end of winter, he corner the Lydian army in front of Sardis itself. He scattered the Lydian cavalry by bringing in camels (which frightened the horses), laid siege to the city, and brought down its walls after only fourteen days. Cyrus thought that his men deserved a reward, so he let them plunder the city of its fabled wealth; it is said, a captive Croesus quipped, "It's not my wealth, it’s yours that they’re stealing". The Ionian Greek cities on the Anatolian coast, as vassals of the Lydian king, were incorporated into Persia too. One powerful rival remained: the Neo-Babylonian Empire. After Nebuchadnezzar's forty-three year reign, the empire had fallen into political infighting and turmoil. The man who finally restored order was Nabonidus (556-539 BC), an influential courtier and experienced general. But he had no royal blood. Nor was he of the Babylonian aristocracy. He was from the city of Harran in former Assyria, one of the main cult centres of the mood-god Sin; his long-lived mother was a priestess there. The new king worked to elevate Sîn's status in the empire. For this, he faced hostility from the influential priests of Babylon's national god, Marduk. Nabonidus' solution was drastic; he turned-over governance of Babylon to his adult son Belshazzar, and ruled the empire from the southern city of Tema. This ultimately weakened Babylon, and gave Cyrus his chance. In 540 BC, he began to send troops into skirmishes all along the Babylonian border. These intrusions became serious enough to make Nabonidus return north, back to the heart of his empire. By the time he arrived, Cyrus had already begun marching on Babylon itself. While Nabonidus began preparing for a siege, he ordered his son to head-off the invaders at Opis on the Tigris river, north of Babylon. The Battle of Opis (September 539 BC) was a decisive Persian victory. Arriving at Babylon, Cyrus realized that it could take months, if not years, to starve the well-prepared city into submission. So he formed another strategy, as explained by the Greek mercenary Xenophon. The Euphrates flowed right through the middle of Babylon. Yet the city was well-used to seasonal flooding, so could not be easily flooded. Instead, Cyrus had his engineers divert the waters upstream, and his soldiers marched along the riverbed, under the city-walls, into the unsuspecting city. On 14 October 539 BC, the greatest city of the ancient world fell to the Persians. Undoubtedly, Cyrus had heard the grumblings of Nabonidus' supposed impiety. He rode into the city as Babylon’s liberator, the avenger of Marduk, and was received as such. He had, after all, more Babylonian royal blood than Nabonidus (his great-aunt had been Nebuchadnezzar's queen); ancient thrones had been claimed on less of a blood relationship. And he had his scribes explain, in the famous Cyrus Cylinder (now in the British Musem), how he improved the lives of Babyonian citizens, and restored temples and cut centres. In exactly the same way, Cyrus famously authorized and encouraged the Jews to return to Jerusalem from their "Babylonian captivity". A little more than a year later, the returned exiles laid the foundations of the Second Temple. The prophet Isaiah saw God's hand in Cyrus, naming him "His annointed one"; the only gentile to be so referred. Cyrus' victory was complete. He took over Nebuchadnezzar's great palace as his winter residence, and kept Ecbatana as his summer palace; high on its mountains, it was much more pleasant than the hot Mesopotamian plain during the summer months. The old Persian capital at Pasargadae remained another of his homes. But for the administrative capital of his new empire, he built himself a new city; Persepolis (a little south of Pasargadae). After swallowing Babylon, Cyrus engage in much warfare to consolidate his rule in eastern Iran. He crossed the Hindu Kush, and set-up some sort of supremacy over the northern part of the Indus Valley; the region known as Gandhara (present-day northern Paistan). Only in the north-east did he find it difficult to stabilize his frontiers. There, Cyrus was defeated and killed, fighting across the Oxus river, up into the wilds of Central Asia, against an offshoot of the Scythians: Herodotus calls them the Massagetae. The defeated Persians were allowed to take the remains of the Great King from the battlefield, and inter them in his capital at Pasargadae.

The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 BC) was the largest empire the world had seen until that time. Its style was different from its predecessors; the "newness" of Cyrus’ empire lay in his ability to think of it, not as a Persian nation in which the peoples must be made more Persian, but rather as a patchwork of nations under Persian rule. Unlike the Assyrians, he did not try to destroy national identities. Instead, he portrayed himself as the benevolent "father" of those very identities. The result was a diverse empire, but a powerful one, commanding loyalties of a kind lacking to its predecessors. Large areas knew longer periods of peace under it than they had for centuries, and it was in many ways a beautiful and gentle civilization. Herodotus tells us that there were many things the Persians could do without more easily than the tulip, which we owe to them. Cambyses II (530-522 BC), the eldest son of Cyrus, was crowned as his successor with no reported opposition. He seems to have suffered from an impulse common to many other sons of great men: he wanted to outdo his father. And he set his eye on Egypt. A fleet was crucial for his ambitions. The Persians had no seafaring tradition of their own; but Cambyses had inherited an empire that stretched all along the Mediterranean coast. So he built himself a fleet using the combined skills of the Ionian Greeks and and Phoenicians, two cultures who had been on the water since the beginning of their history. By the sixth century BC, no true navy had existed either in Greece or Egypt. Persia became the first empire, under Cambyses, to inaugurate and deploy a regular imperial navy. Four years after his coronation, Cambyses' fledgling navy began its journey down the coast, while the Persian army marched across the Sinai desert towards the Egyptian frontier. Amasis II (570–526 BC) was on the Egyptian throne when word came down of the approaching invasion. Amasis readied his own forces at Pelusium, an important fortress in the eastern extremes of the Nile Delta. But he was already in his seventies and had led a long and very busy life. Before Cambyses could arrive, Amasis died. This was a bit of very good luck for the Persians, since Amasis's son Psammetichus III was not a gifted general. As soon as the Battle of Pelusium (May 525 BC) began to turn against the Egyptians, Psammetichus pulled them back all the way to Memphis. This gave the Persians virtually free access to the waterways of the Delta, allowing them to besiege Memphis both by land and by sea. We have no details of the resistance that followed, but Psammetichus was soon forced to surrender. He had been pharaoh for less than a year. Cambyses now styled himself pharaoh of Egypt, made sacrifices to the Egyptian gods, and used propaganda to portray himself as a liberator; a now familiar strategy. The new pharaoh did not spend long in Egypt; he put a governor in charge, and hurriedly left to take care of other business. But his tenure was a short one. Three years after his Egyptian conquest, Cambyses died suddenly, mysteriously, and without an heir.

Darius the Great, from the central relief of the northern stairs in the great hall at Persepolis.

The ancient sources surrounding the ascension of Darius the Great (522-486 BC) to the Persian throne are so contradictory that any reconstruction of the events is uncertain. Herodotus repeats a story created by Darius to justify his own usurpation which portrays Cambyses as a cruel tyrant. Before his Egyptian campaign, Cambyses had secretly assassinated his own younger brother Bardiya. In his absence from the capital, however, a pretender who claimed to be Bardiya attempted to seize the Persian throne; as the assassination had been in secret, the Persians still believed him to be alive. Cambyses was over in Syria when he heard the news. He ran for his horse, and accidentally stabbed himself in the thigh while mounting; the wound turned gangrenous and he died three weeks later. With Cambyses dead, the imposter managed to hold onto the Persian throne for seven months. The charade could not go on forever, though. Eventually, a group of seven Persian noblemen, Darius among them, mounted a successful coup against the "fake Bardiya". These seven men then had a very reasonable (and highly unlikely) debate about which of them should be the new king, and concluded that Darius was the natural choice. There are lots of question marks in this story. Modern historians suspect Cambyses died (perhaps naturally, perhaps assassinated), and then the real Bardiya ruled for a few months, until assassinated by Darius. Whatever happened, Darius' reign was one of the most important periods of Persian history. The new king immediately faced rebellions all across the empire; most notably in Babylon, led by a man who claimed to be the son of Nabonidus. These risings, however, were suppressed and quelled in an amazingly brief time. Darius had a new vision for the Persian army. Cyrus had relied on unwieldy masses of conscript soldiers, fighters sent to his as tribute; numbers to overwhelm the enemy by sheer size. Instead, Darius established a professional army, one that would be smaller, but better trained, better fed, and more loyal. It had an elite core of ten-thousand, all of them Persians or Medes. who were bound together so strongly that they jealously guarded entrance into their own ranks. Herodotus calls them “The Immortals" because there was always exactly ten-thousand men; every killed or seriously wounded member was immediately replaced with a new one. Darius was as remarkable an administrator as a general; a rare combination. He completed the organization of the empire, begun by Cyrus, into twenty provinces (satrapies), which were each assigned a trustworthy governor (satrap), and fixed the annual tribute due from each province.Satraps who did not send the proper amount, or did not keep their provinces in order, were liable to be executed. We get a glimpse of this in the Book of Ezra. The satrap who had the watch over Jerusalem noticed that the construction of the Second Temple (and particularly its outer walls) had progressed to a worrying degree; it looked more like a defensive citadel, than a temple. This satrap, a man named Tattenai, ordered the work to stop until he could report to Darius. The Jews protested that Cyrus had given them permission, but Tattenai was not willing to take the risk. Eventually, Darius did give the Satrap permission to let the building go ahead, but the Biblical account was not sympathetic to Tattenai; a man who no doubt feared the seeds of rebellion and the lose his head. Alongside other innovations in centralized administration, Darius introduced a new uniform coinage, the daric; standardized weights and measures; used a common language, Aramaic (the old lingua franca of Mesopotamia) across its territory; expanded the network of roads; and instituted a postal system, based on relay stations for the change of horses, so that messenges could be conveyed at two-hundred miles a day. While these measures united the diverse peoples of the empire, Darius followed Cyrus' example in respecting native faiths and religions. While there is no scholarly consensus on the religious beliefs of his predecessors, Darius in his inscriptions appears as a fervent believer in Zoroastrianism; its introduction as the state religion of Persia is often attributed to him. Darius was the greatest builder of his dynasty, and, during his reign, Persian architecture assumed a style that remained unchanged until the end of the empire. In Susa, the former Elamite capital, he built a new palace complex in the northern part of the city, which became his favourite residence. At Persepolis, in old Persia, Darius founded a new ceremonial capital to replace the old one at Pasargadae. The city was in the end a collective creation; later kings made their own additions, and embodying it with the cosmopolitanism of empire. Assyrian colossi (human-headed bulls and lions) guarded the Gate of All Nations, as they had done in Nineveh. Up the Great Stairway marched stone warriors bearing tribute, carved by Ionian artisans. The many decorative columns, and rock tomb cut into the cliff face recall Egypt. These monuments fittingly express the continuing diversity and tolerance of Persian culture. After securing his authority over the existing empire, Darius turned his eyes to new frontiers. In the east, he hoped to conquer the Indus river valley. The Persians had reach the river under Cyrus, but he had no idea where it went. So he hired an Ionian sailor named Skylax to lead an expedition to explore the region. He is said to have sailed down the river to the sea, and then sailed west, around the Arabian Peninsula, to reach Suez on the Red Sea. Darius then conquered the lands from Gandhara to modern Karachi. The Persian Empire, bulging-out in almost all directions, made little progress to the north-west, ultimately provoing the Greco-Persian War.

Greco-Persian Wars[]

The Greco-Persian Wars (499-479 BC) is the climax of the early history of Ancient Greece, and the inauguration of its Classical Age. Because the Greeks made so much of their long struggle with the Persians, it is easy to lose sight of the many ties that linked the two belligerents. The Persian fleet - and to a lessor extent the Persian army - launched against them had thousands of Greeks, mainly from Ionia, serving in them. Cyrus had employed Greek stone-cutters and sculptors; Darius had a Greek physician. The war itself did as much to create and feed the antagonism; however deep the emotional revulsion proclaimed by the Greeks for a nation which treated its kings like gods. But myths breed future realities, for in the repulse of an Eastern despot by Greek freemen lay the seed of a contrast often to be drawn by later Europeans; the first of many episodes in which Europe confronted Asia and won.

Depiction of Persian soldierss from the Palace of Susa. Their garments match the description by ancient authors of the standing army known as the Immortals. This elite corp of 10,000 was precisely decimal: ten battalions of 1000 were divided into companies of 100, and squads of 10. The armies' tactics emphasised maintaining their distance from the enemy in order to defeat them with their chief weapon; the bow. Along with the elite corp, there were conscript soldiers from allies in the tens of thousands.

The origins of the war lay not with the Greeks, but with the Scythians. These nomads, who still lived north of the Black Sea, had taken advantage of the disorder of Darius' early reign to raid Persian territory. To punish them, Darius did not plan to advance directly across the Caucasus Mountains; rather, he decided to attack the Scythians from the rear. Accordingly, he would lead his troops across the Bosphorus strait into Europe, and then cross the Danube into Scythian territory. In 513 BC, the Persian army began its long march along the new road from Susa all the way to Sardis in Anatolia. Meanwhile, an Ionian Green engineer named Mandrocles had taken the measure of the strait. It was not a particularly impressive expanse of water, but no eastern empire had yet crossed it. At around 720 yard, it was far too wide for a traditional bridge, so Mandrocles designed a pontoon bridge of low, flat-decked boats, roped together; the first in recorded history. Thousands of Persian foot-soldiers and cavalry crossed the bridge, and then march all across Thrace to a narrow place in the Danube, where another pontoon bridge awaited. The Greek cities of Thrace made no attempt to block the advance; they were afraid of the Scythians too. The Scythians did not line up in opposition. Instead, they retreated constantly before the Persians, while harassing the enemy and systematically destroying laying waste to the countryside. Darius pushed deep into Scythian lands, where there were no cities to conquer and no supplies to forage. But he was never able to bring them to a pitched battle. Finally, the Great King halted the march at the banks of the Volga; his entire army headed back to the Danube, and, over the pontoon bridge, into Thrace. Despite the evading tactics, Darius' campaign was enough to force the Scythians to respect Persian power. But he would not leave without spoils. Darius himself returned to Sardis, but left the army to a trusted general named Megabazus, with orders to conquer Thrace. The Thracian Greek cities, which had hoped for deliverance from the Scythian threat, now found themselves falling, one by one, under Persian rule. Megabazus was a capable general, but his task was made easier by the fractured nature of Thrace; each city had its own ruler, its own army, and no common purpose. After turning Thrace into a new Persian satrapy, Megabazus set his eyes on Macedonia. The Macedonians stood between the Thracian colonies and the city-states of Greece proper; and differed from both. Their cities all belonged to a single kingdom, ruled by a single king. In 510 BC, the year that the Persians appeared on the horizon, its king was Amyntas (d. 498 BC). Amyntas, seeing a well-conquered Thrace behind them, decided at once that resistance was futile. In keeping with Persian practice, Megabazus dispatched seven envoys to demand "earth and water", symbolizing dominance over the land and sea of a subject land. And Amyntas agreed. This alliance would turn out to be very good indeed for Macedonia; neither Greeks nor nomads troubled her borders, since to do so would risk Persian wrath. With Macedon now a Persian ally, there was little barrier now between Persian ambitions and the Greek peninsula.

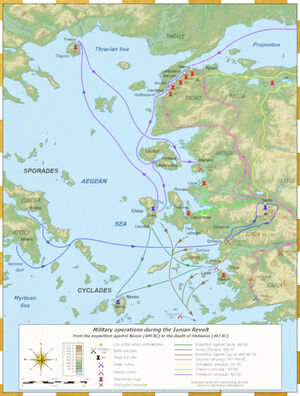

At this point, there was something of a pause, until a troublemaker provoked a direct confrontation between Greece and Persia. He was Aristagorus (d. 496 BC), a "tyrant" who had long dominated the Ionian Greek city of Miletus, on the edge of Persian ruled Anatolia. The Persians found the Ionians difficult to control, because there was no aristocracy to help them rule, only a fractious populace; so they tended to sponsor a tyrant in each Ionian city. Aristagorus was an ambitious man, who fancied ruling a mini-empire. He went the the Persian provincial governor (satrap) at Sardis, and offered to conquer the nearby islands on behalf of Persia, if the Persians would fund his campaign. With the plan agreed, Aristagorus set sail for his first target, the island of Naxos; the inhabitants hauled all of their provisions inside the city, and withstood a four month siege, until Aristagorus ran-out of Persian money. Aristagorus was now caught in a bind; the Persians would no doubt remove him from power, due to his failure to make good on his promises. In a desperate attempt to save himself, he turned on a dime from pro-Persian to anti-Persian. He would lead the Greek cities of Anatolia in an Ionian Revolt (499-493 BC). But he had learned from his Naxos debacle that wars were expensive; he needed strong allies. The first obvious choice was Sparta, the pre-eminent Greek city in matters of war. However, despite Aristagoras's entreaties, the Spartan king Cleomenes (d. 490 BC) not only refused to poke the Persian beast; he first laughed at Aristagoras and then pitched him out of the city. He was better received in Athens. Hippias, the expelled Athenian tyrant, had gone to Persia to seek help in recovering the city. The Athenians granted Aristagoras the help of twenty ships, each carrying perhaps twenty hoplites; its ally Eretria sent five more. The Ionian Revolt began on a high note. Aristagoras and his allies managed to surprise Sardis. The satrap and his troops shut themselves safely into the citadel, but the city (by plan or accident) went up in flames. Darius immediately sent his fast and well-trained army to put down the revolt. When the two armies met near Ephesus, the Greeks were soundly thrashed. After this defeat, the Athenians, seeing no good coming from the revolt, decided to go home But the Ionians had no choice but to fight on; burning Sardis had been a point of no return. They enjoyed some success off-shore. A joint Ionian fleet sailed up and down the coast, collecting allies as they went; Byzantium and Cyprus also rebelled against the Persians. This stymied the Persians until 494 BC, when a large Persian fleet caught-up with their Ionian counterpart just off the coast, near Miletus. The Persians had prepared themselves for a huge encounter, but, as soon as the battle turned against the Greeks, scores of ships lost heart and deserted. Aristagorus himself sailed off to Thrace, where he was killed attempting to seize power in the Greek colony of Amphipolis. The victorious Persians took ferocious revenge on Miletus, the city of the troublemaker. The city was stormed and burned to the ground; its population sold into slavery. Worse was to come.

The Battle of Marathon was a watershed in the Greco-Persian Wars, showing the Greeks that the Persian juggernaut could be beaten. The men who fought there were later known as Marathonomachoi, honoured as World War II veterans have been in 20th century. Their victorious general Miltiades came to a thankless end, though. The following year, he led a failed expedition to capture the Persian-held island of Paros. His failure prompted an outcry in Athens, enabling his political rivals to charge him with treason. He was brought to his trial suffering from a grievous leg wound received during the failed campaign, and died in prison, probably of gangrene.

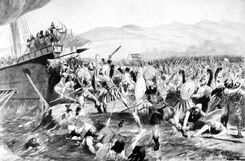

Darius had not forgotten the original Athenian and Eretrian participation in the revolt. In 492 BC, he put his general and son-in-law Mardonius (d. 479 BC) in charge of a two-pronged invasion force; a large army would cross the Bosphorus and march through Thrace and Macedonia down into northern Greece; and a naval fleet would sail across the Aegean to join them for the attack on Athens and Eretria. This first foray into Greece was cut short. The fleet was moving along the Thracian coast, when caught in a violent storm and partly wrecked near the promontory of Mount Athos. It took the Persian navy two years to build. But by 490 BC, Mardonius was back on the job. Herodotus claims that six-hundred warships accompanied perhaps twice as many transports. Even if that is an exaggeration, the fleet was big enough for Mardonius to decide on a purely amphibious operation; a choice force of infantry and cavalry would be carried by the fleet. The Persian fleet proceeded to island-hop across the Aegean, subduing them one by one; Naxos was overrun in a matter of days, suggesting that Aristagorus had not been a particularly competent general. The first major goal was Eretria, on the island of Euboea, north of Attica. The Eretrian strategy was to withdraw within the city-walls, and undergo a siege. However, rather than a passive siege, the Persians vigorously assaulted the walls for six days, with heavy losses on both sides. On the seventh day, two reputable Eretrians betrayed the city to the Persians. With Eretria gone, the Athenians, braced to face the Persian cataclysm, sent a messenger named Pheidippides to Sparta to beg for aid. He is said to have covered the 140 miles in between Athens and Sparta in two days; even if Herodotus exaggerated the time, there is no doubting the distance. But the Spartans were celebrating the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and could not march until the full moon. It seems very possible that they were attempting to avoid outright war with Persia; whose wrath was directed at those Greek cities which had joined in the Ionian Revolt, and Sparta had declined. Meanwhile, the Athenians had no choice but to face the Persians alone; except for a small force from Plataea. Meanwhile, the Persians headed south down the coast of Attica, landing at the bay of Marathon, roughly twenty-five miles from Athens; they assumed the Athenians would never dare attack them that far away, since it woud leave their city unprotected. But Miltiades (d. 489 BC), the Athenian generals with most experience against the Persians, convinced the Athenians to take that risk; the Battle of Marathon (September 490 BC). The Persians found themselves pinned against the shore. Their strength was cavalry, but they could not use it; the infantry could be disembarked quickly, but disembaring the horses could exposed them to an attack while in disarray. Herodotus tells us that Miltiades arranged the Athenian hoplites in a slightly unorthodox formation, with a thin centre and massed ranks on both wings. And in fact, the Athenian centre broke almost at once. The massed wings, though, quicked routed the Persians on the flanks, before turning inwards to surround the Persian centre. The Persians had no other recourse except to run back towards their ships, pursued by the Greeks. According to Herodotus, the Athenians killed 6,400 Persians at a loss of 192 of their own men, but they did not succeed in getting hold of the Persian ships before they could launch; capturing only seven. Even so, the Battle of Marathon was a staggering Athenian victory; the Spartans arrived in time to help count the dead.

A bronze statue of the Spartan king Leonidas, erected at Thermopylae in 1955. An inscription reads simply "Come and take them", which was Leonidas' laconic reply when Xerxes offered to spare the lives of the Spartans if they gave up their arms. Even during its decline, Sparta never forgot its laconic wit. An anecdote has it that when Philip II of Macedonia sent an ultimatum saying "If I invade Sparta, you will be destroyed, never to rise again", the Spartans responded with a single word: "if". This is why the English word "laconic" derives from the old Greek name for the Spartans; the Lyconians.

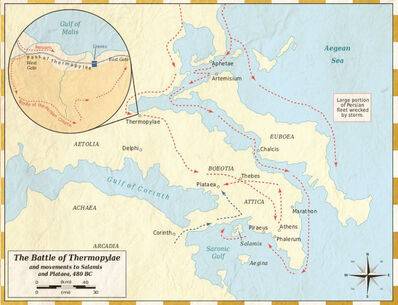

In the immediate aftermath, Darius vowed to raise a second invasion force, which he would lead himself; but he had no time. He fell ill in the fall of 486 BC, and died before winter came; thus leaving the task to his oldest son, Xerxes (486-519 BC). Xerxes had been taking notes on his father’s career. Like Darius, he first faced the opportunistic rebellions that always accompanied a change in the royal house. In Babylon, he dealt with the unrest by dividing the previously large satrapy into smaller sub-units, short-circuiting some of its factionalism. Egypt he reconquered by sheer force of arms, and then abandoned the title of "Pharaoh", carving simply “King of the Persians and the Medes” into inscriptions all over the country. By 484 BC, Xerxes had turned his eyes back to Greece. Patient preparations for his expedition required three years to complete; troops were levied all over the empire; ports set to building a fleet, intended to be the army’s supply line; and massive engineering works were undertaken, including a canal across the peninsula of Mount Athos (to avoid the catastrophe which had struck the expedition of 492 BC), In the fall of 481 BC, Xerxes in person marched his troops to Sardis, where they wintered. In that same year, almost all of the Greek cities joined together in a new league, the Hellenic League, formed specifically for the defence of Greece against the Persians. Little is known about the internal workings of the league, but overall command was conferred on Sparta, Even Athens, whose strengthen was of her fleet, accepted this. Having crossed into Europe in the spring of 480 BC, the Persian army began its march to Greece. The Greeks said, and no doubt believed, that the Persians came in millions; if, as now seems more likely, there were well under a hundred-thousand of them, this was still an overwhelming enough number. They had little faith that the north would stand for very long. The Greeks established their defensive line at Thermopylae, just below the Malian Gulf, where the mountains divided to allow only a narrow pass. This was the only decent way for Xerxes to reach the southern part of the peninsula. Their fleet was drawn up at the north end of Euboea, to prevent the Persians bypassing Thermopylae by sea. There they waited, seven-thousand hoplites from various cities under the Spartan king Leonidas (d. 480 BC). Behind them, Greece was in full preparation for disaster. The Athenians evacuated all their women, children, and old men en masse to the safety of Salamis island. And then Xerxes swept down. For two days, he hurled his best troops into the narrow pass, but the Greek phalanx held firm. The situation appeared to be an impasse; until resolved by treachery. A certain Ephialtes defected to the Persians, and informed Xerses about a hidden mountain track that would bring his troops, unseen, to the other side of the pass. A contingent of 20,000 elite troops, Immortals, took that route during the night. Before dawn, spies brought Leonidas news of the imminent encirclement. Realizing that the battle had already been lost, he ordered all of the Greek forces, except for his personal bodyguard of three-hundred, to retreat back down south. With these last three hundred (along with a few troops from Thebes and Thespia who refused to leave), he fought a delaying action against Xerxes. Athens was doomed, but if the retreating Greeks could reach the Gulf of Corinth, they might still be able to hold the Peloponnese; all that would remain of Greece. The Spartans fought until they were wiped out, selling their lives at a high price. Herodotus writes that the terrified enemy had to be whipped into confronting these Greeks; two of Xerxes’ own brothers were alain. The heroism of the doomed rearguard became an enduring monument to Spartan valour, captured in a famous epitaph inscribed on a column in the pass: “Stranger, go tell the Spartans that here we lie, obedient to our laws”. But Xerxes was unimpressed; he ordered Leonidas’ head impaled on a spike and his body crucified, like an common criminal.

After Thermopylae, it is said, the retreating Greeks had a brief and violent quarrel about what to do next. The Athenians begged the others to make a stand in Attica, to defend their great city. But the rest of the Greeks, recognising that such a broad northern front could not be held, won the day. The entire army retreated back to the narrow land bridge, the Isthmus of Corinth, that connects the Peloponnese peninsula to the rest of mainland Greece; and massed their fleet in the narrow strait separating Attica from Salamis. The Athenians did so under protest; “angry at this betrayal,” Plutarch writes, “and dismayed at being deserted by their allies”, Meanwhile, Xerxes marched in triumph to Athens, and ordered the city to be torched. From the other side of the water, the Athenian refugees on Salamis were forced to watch their great city burn. The next events are chronicled by the playwright Aeschylus, who was there. The Athenian statesman Themistocles (d. 459 BC) knew that time was on the Persian side. The best strategy for Xerxes was a slow and damaging war of attrition; to leave the Greeks penned-up in the Peloponnese, and use his fleet to prevent aid from allies on the outlying islands. So Themistocles sent a message to the Great King feigning to defect; intimating that the fragile Greek alliance was breaking-up, and, if he attacked at once, the dispirited Greeks would scatter. This was exactly the kind of news that Xerxes wanted to hear. He took the bait, and the Persian fleet sailed into the Straits of Salamis; the Battle of Salamis (September, 480 BC). Both sides had very similar ships, the triremes, long thin ships with room for 170 oarsmen, which meant they could knife through the water and ram other ships at high speed. But in the cramped strait, the larger Persian numbers were an active hindrance, as ships struggled to manoeuvre and could not retreat because their lines were several ships deep. By the afternoon, Greek victory was assured and the remaining Persian ships limped back to Pireus, the port of Athens. This defeat need not have been the end for Xerxes, but his rage ruined him. He ordered the captains put to death for cowardice; all Phoenicians, for the Persians raised inland were no sailors. This turned every Phoenician sailor against him, and scores of them sail for home when night fell. With his naval capability in disarray, Xerxes feared that the Greek might sail to the Hellespont and destroy the pontoon bridges. And he decided to go home. He marched back up through Macedonia and Thrace with the bulk of his army, leaving behind a group of troops under his son-in-law Mardonius. In effect, Xerxes was leaving Mardonius to die, to save himself the ignominy of out-and-out retreat. The Persians were still occupying Attica, with an army that more than matched Greek numbers. After a long series of manoeuvres, in which Mardonius tried to lure the Greeks into open terrain where he could use his cavalry, the two sides eventually met near the city of Plataea, on hilly ground. There, at the Battle of Pausanias (August 479 BC), the Persian infantry, once again, proved no match for the heavily armoured Greek hoplites and rigid discipline of the phalanx formation; the Greeks were victorious and Mardonius died on the battlefield. This was a two-pronged attack. The Greek navy had simultaneously pursued the remnants of the Persian fleet across the Aegean, all the way to the coast of Anatolia. The Persians, seeing Greeks behind them, decided not to risk another sea battle; they beached their ships on the shores near Mount Mycale, and lined up to fight on land. At the Battle of Mycale (August 479 BC), the Persians relied on Ionian Greek contingents within their ranks to back them up. But, as the Greeks approached, the Ionians melted away. The Persians stood their ground for a while, but eventually broke and fled. The Greeks chased them all the way back to Sardis, killing as they went; only a handful ever reached the safety of Sardis’ walls. Tradition held that both battles, Plataea and Mycale, took place on the same day. This was the end of the Greco-Persian War. For Xerxes, the sack of Athens was probably enough to allow him to present himself as a returning hero. For Greece, however, the victory not only guaranteed her freedom from foreign rule, but opened an age of huge self-confidence.

Classical Greece[]

Victory over the Persians launched the greatest age in Greek history. Some have spoken of a "Greek Miracle", so high do the achievements of Classical Greece (510-323 BC) appear. Yet those achievements had as their background a political history so poisonous and embittered that it ended in the demise of the very institution which nurtured classical civilization; the city-state. A century and a half later, men were to look back at the heroic days of Mycale and Plataea, and wonder if some great chance to unite Greece as a nation had not then been missed forever.

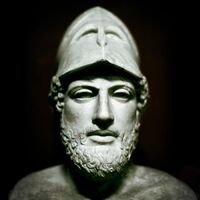

Bust of the Athenian statesman Pericles; a Roman copy of a Greek original from 430 BC. After the Persian war, Pericles came to dominate Athenian politics, and pushed his own plans for Athenian security; these involved maintaining a common Greek fleet, and sailing around to shake money out of the smaller Greek cities.