| Crusading Age | |

| Period | High Middle Ages |

| Dates | 1095-1204 AD |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by Era of the Normans |

Followed by Rise of State Power |

| “ | Christians are right, pagans are wrong | ” |

–The Song of Roland | ||

The Crusading Age lasted from about 1095 AD until 1204 AD. It began with the First Crusade, which set the precedent for the heady blend of religious idealism and astonishing barbarity. It then ended with the bizarre Fourth Crusade, where an armed expedition launched by the papacy sacked the largest and oldest explicitly Christian city in the world.

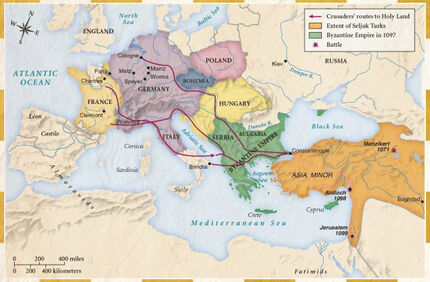

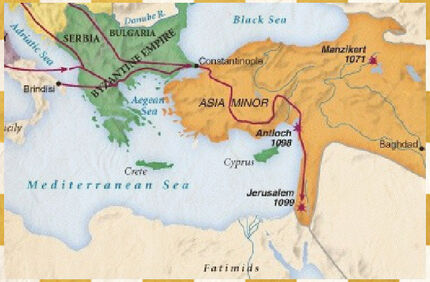

In 1094, the Byzantine Emperor wrote a fateful letter to Pope Urban II, asking for military assistance against the encoraching Muslim Turks in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). The help he sought was merely some Western mercenaries; what he got was the First Crusaders. The ideology of Crusading was already much in the air because of developments in Spain, where the Reconquista had recently recovered the prestigious city of Toledo. Pope Urban II first issued his call at a council of French bishops and nobles at Clermont in 1095, In an emotive appeal at the Council of Clermont, Pope Urban II called for Western nobles and knights, rather than pursuing strife among themselves, to take the cross against the enemies of Christianity, with the ultimate goal of conquering Jerusalem. Soon it seemed that entire nations were on the move as Crusading fever swept Europe, sparking violence even before their departure against local Jewish communities. The fervour and moral exaltation of the movement was undeniably a genuine manifestation of Christianity. But that was only one side of the coin. Crusading warfare provided a licence for the predatory appetites of the feudal elites; they could plunder booty and land from the infidel with a clear consience. Against the odds, the fractious and naive First Crusade (1095–99) was miraculously successful. Within three years the Latin Christians had recovered Jerusalem, where they celebrated the triumph of the Gospel of Peace with an appalling massacre of its inhabitants, even by the low standards of the day. In the East they briefly established new Crusader States; the kingdom of Jerusalem, and its nominal vassals of Antioch, Tripoli, and Edessa.

The nature of Crusading proved unsuited to the defence of the Holy Land. Religious fervour was difficult to direct and control, while European knights usually returned home once their personal pilgrimage was complete; it was standing armies that the Latin Christian states needed, not short-lived expeditions. Moreover, the success of the First Crusade owed much to a passing phase of weakness and anarchy in the Islamic world. Zengi, a Seljuk general, saw the possibilities of exploiting Christian mistreatment of the local Muslim population to build-up a powerful sultanate in Syria. In 1144, he recovered Edessa, shocking the West and the Pope into calling for the Second Crusade, though it accomplished almost nothing. Zengi's son, Nur al-Din, went on to extend power in Egypt too, establishing a single Muslim state completely surrounding the Latin kingdom. It was a usurper of this sultanate, Saladin, who proved the West's greatest nemesis of the Crusading Age. He remains a captivating figure even after strenuous efforts by sceptical historians to cut-through the romantic image of the "chivalrous Saracen"; a man of his word and just in his dealings. Saladin’s first great triumph was the recapture of Jerusalem in 1187, which provoked a new Third Crusade. Richard the Lionhead was a worthy opponent to Saladin, twice marching to within sight of Jerusalem, but eventually realised that, even if he could recover it, he could never defend a city so far from naval support.

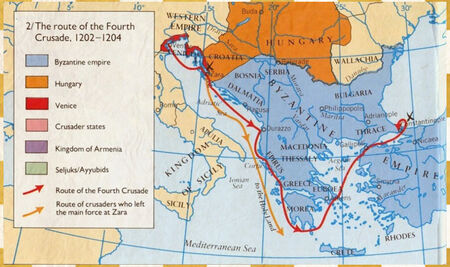

The first three Crusades had brought greater contact between the Latin West and Orthodox East, but familiarity, however, did not lead to a greater understanding. It may have been too obvious that many Byzantines thought of the Latins as greedy barbarians. It was certainly too obvious that Constantinople had little sympathy with the Crusader States, which always enjoyed a warm glow of religious frontline commitment in the minds of Western observers. The tone of awe at the great city's grandeur steadily transitioned to a view of the Greeks as duplicitous, decadent, over-clever, and ungrateful cowards; even their religious practices were suspect, for the Great Schism had been in effect now for a century-and-a-half. The idea of conquering the largest, wealthiest, and most sophisticated Christian city in the world was unthinkable to most Europeans, but that is what happened. Though a bizarre combination of cock-ups, financial constraints, Venetian cynicism, and Byzantine in-fighting, Constantinople was brutally sacked in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade, and a new Crusader State set-up in its stead. The Byzantine government nevertheless survived in exile and recovered Constantinople in 1261, but the damage was done; the heart had gone out of Byzantium, though it had still two centuries in which to die. This event far from discredited the Crusading ideal which continued throughout the 13th-century, though with little success. Under the ruthless Baybars and his successors, the Muslims finally swept the Latin Christian states from the Holy Lands in 1291.

The Crusading Age had profound consequences for all those involved. It created an enduring sense of unbridgeable ideological separation between Christianity and Islam. Among other things ending the possibility of the two religions living side by side, as they had oftern done in Spain and Sicily. The division of Christendom was embittered too. The sack of Constantinople left a deep sense of betrayal, so quickly forgotten by the West, that endured in the memory of their Orthodox co-religionists; the Great Schism endures today. The other side of this coin is that, for two centuries, the Crusades bound Western Europe together in a great moral and spiritual enterprise. It fed their own sense of identity, that the people of Europe did share a common civilisation and cultural heritage. A material effect was that trade between East and West increased phenomenally during this period. This may have occurred anyway, for Western Europe’s population, wealth, and demand for sophisticated Eastern products was growing, but the Crusades hastened the developments. The Crusades have cast a very long shadow indeed, in a new temper in Latin Christianity, a militant tone and an aggressiveness which would often break out in centuries to come. In it lay the roots of a mentality which, when secularized, would power the world-conquering culture of the modern era. Modern Islamic nationalism has drawn parallels between the Crusades and political developments such the establishment of Israel in 1948, as well as encouraging ideas of a modern jihad against Western states

History[]

Byzantine Faltering[]

Under Emperor Basil II (d. 1025), the Byzantine Empire reached the zenith of its medieval power and dignity. The conquest of Bulgaria and the Slavic Balkans created a more stable and secure border, safe from Magyar (Hungarian) and Turkic Khazar raiders. The Balkans, Greece, Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), northern Syria, and the south Italian mainland were under stable Byzantine control, all governed by a single and cohesive political system with a complex fiscal structure that the West would not match for centuries. Constantinople itself, at probably half a million inhabitants, was the largest city that ever existed in medieval Europe, renowned as far away as Scandinavia, where it was known simply as, "the City". The Macedonian Renaissance was taking effect, seeing the assimilation of classical hellenic styles into Christian art, and the University of Constantinople as the main source of Christian learning for its day. Basil had even managed to leave a burgeoning treasury, despite fighting military campaigns so regularly. Yet, it took his successors just 46-years to squander his legacy and engineer such a disastrous defeat at Manzikert that the empire never recovered.

Basil II never married and left no heir, so was succeeded by his worthless brother, Constantine VIII (d. 1028) and his family. Over the next 56 years, there were no less than thirteen emperors, none with any particular political or military talent. They allowed the state increasingly fell into the hands of a poisonous court, dominated by two self-interested factions; the urban aristocracy of Constantinople, and landed aristocracy of the provinces. Each faction put-up rival emperors from the royal family. The sophisticated urban aristocracy favoured men who would expand the imperial bureaucracy, thus supplying them and their families with lucrative offices and decorative titles; rapidly draining the treasury in the process. The provincial nobility, who had been punished by Basil's legislation, wanted emperors who would give them free-rein to expand their estates and exploit the rural peasantry. Before the 11th-century, great landowners had never been locally dominant within the empire, with a substantial free-holding peasantry, as well as the tenant peasant-militia of the theme estates, who formed both the backbone of the army, and a major source of tax receipts. Now peasants found themselves increasingly falling under a form of feudal serfdom. The unfortunate consequence of all this was the army and navy were starved of funds and manpower, at the very moment that new enemies were appearing on almost every frontier almost simultaneously. To the north, the Byzantines had long maintained relatively good relations with Kievan Rus' and the Khazars, but in the late-10th-century both were pushed aside by more aggressive peoples, steppe nomads such as the Pechenegs and Cumans, whose raids into Thrace and Macedonia became a constant menace. Meanwhile, Western Europe too was revealing itself to be a predator, beginning with the Norman conquest of Byzantine southern Italy and religious strife between Constantinople and Rome that culminated in the Great Schism of 1054; that the Byzantine Empire had for centuries absorbed much of the Islamic onslaught which might otherwise have fallen on the West, would not save her. The last capable Byzantine general in southern Italy, George Maniakes, fell victim to court intrigue in 1043, and the Normans made steady progress after that. But the greatest danger was the eastern frontier, where the arrival of the Seljuq Turks was to change the whole shape of the Muslim and Byzantine worlds.

The Battle of Manzikert, a turning point in the story of the Byzantine Empire. The victorious Seljuk Turks captured the Byzantine Emperor, and, with the empire in disarray as generals squabbled for the throne, nothing could stop them sweeping across Anatolia.

Having conquered Persia and wrested political authority from the Abbāsid Caliphs of Baghdad by 1055, the Seljuks made their first incursions across the Byzantine frontier into Armenia in the late 1050s, where they found an empire whose once-formidable military had been allowed to decay to the point of incompetence. They began by systematically reducing the Byzantine defensive system, a chain of fortresses stretching from the Caucasus to Syria. The first to fall, Ani in 1064, became their base-of-operations for the rest of the campaign, which three years later had reached as far west as Caesarea in central Anatolia. The emergency lent weight to the provincial noble faction, who secured the election of one of their own as emperor, Romanus IV Diogenes (1068-1071). Romanus was at least a capable general, who assembled a 40,000 strong army and took it east in a series of campaigns that culminated in the disastrous Battle of Manzikert (August 1071). It was a sign of the times that his army was mainly composed of conscripts and foreign mercenaries. At Manzikert, Romanus slightly outnumbered his enemy, and might have won, if his position had not been undermined by the unreliability of mercenaries and treachery within his own ranks. He made the foolish mistake of trusting his reserves to a political rival, Andronikos Doukas, a prominent member of the urban noble faction, which had held the throne until Romanus' elecation. When the right flank of the Byzantine line began to falter, Doukas failed to support it, throwing the entire army out of cohesion. Romanus, who was leading the center, had to watch as the mercenaries on the left flanks fled the field, leaving dangerously exposed. He made a defiant stand alongside his Varangian Guard, fighting valiantly even after his horse was cut from under him, but in the end was encircled and captured. Byzantine scholars would later look back and lament Manzikert as the moment the empire's precipitous decline began. But the defeat didn't have to be the long-term catastrophe that it became. Compared to other famous Roman disasters such as Cannae or Adrianople or Yarmouk, the casualties at Manzikert were quite modest at 5,000; barely an eighth of the army. Moreover, the Seljuks were distracted by war with Fatimid Egypt, and released Romanus just a week later, in return for a not ungenerous peace treaty. A capable emperor could have salvaged the situation. Instead, chaos reigned as Byzantium's resources were squandered in a decade-long series of civil wars over the throne. Romanus himself returned to Constantinople to find the Doukas family had already usurped the throne. Despite attempts to raise loyal troops, he was defeated, deposed, cruelly blinded, and endured a painfully lingering death. The beastly or incompetent emperors who followed him, lost in their petty squabbles, refused to honour the peace treaty with the Seljuks. The Turks thus felt justified in continuing their campaign, and by 1081 had reached Nicaea. The heart of the empire’s military and economic strength in Anatolia, which the Arabs had never mastered, was now under Seljuk rule.

Alexios I Komnenos, among the last of the great Byzantine Emperors. He inherited an empire riven by factionalism and surrounded by enemies, but overcame a series of crises to inaugurate a century of modest recovery.

The final straw for Byzantium was the disastrous reign of Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates (1078-81). The new emperor was at least a general, but, at 78-years-old, he had used what energy he had left on a successful bid for the throne. Once there, he rapidly sank into debauchery and senility. As a usurper, the most pressing problem as Nikephoros saw it was shoring up his legitimacy. He thus married Maria, the beautiful 29-year-old widow of the emperor he had just ousted. He then made matters worse by reneging on a promise to name Maria's son as heir. The boy's father-in-law was not amused, the brilliant Norman adventurer, Robert "Guiscard" de Hauteville (d. 1085). Guiscard, on the lookout for just such a pretext, immediately sailed from southern Italy, and invaded Byzantine Greece. In this new crisis, Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118), the ablest general of his day, seized the Byzantine throne in an almost bloodless coup; accepting his fate, Nikephoros abdicated and retired to a monastery. Many who watched Alexios' coronation must have done so without much enthusiasm, seeing just another in a long line of usurpers. Indeed, the empire seemed almost beyond saving. Although his 35-year reign was full of struggles, Alexios would prove one of the last great Byzantine emperors. The history of his reign was written in elegant Greek by his daughter Anna Komnene; and, as she remarks, it began with an empire beset by enemies on all sides. Robert Guiscard, and his equally formidable son Bohemond (d. 1111), were besieging Dyrrhachium (modern-day Durrës in Albania), the main Byzantine fortress on the Adriatic coast. Alexios decided to confront his enemies head-on, but the resulting Battle of Dyrrhachium (October 1081) exposed all the flaws of the ill-disciplined mercenary-based Byzantine army; Alexios himself barely escaped the rout. Dyrrhachium soon fell, but if Guiscard thought that Alexios was beaten, then he was soon to learn that there was more to war than fighting. Alexios immediately began plying the diplomatic waters, seeking allies. The German king-emperor, Henry IV, proved immediately receptive, in the midst of his quarrel with Pope Gregory VII, a Norman ally. Then to make doubly sure, Alexios made an alliance with the Republic of Venice to harass the Norman navel supply-lines, bought at the cost of extensive trading privileges within the Byzantine Empire that would have unforeseen long-term consequences. Guiscard was forced to return to Italy to support the Pope for four years, leaving Bohemond to continue the campaign alone. Over the next few years, Alexios harassed the Normans, while simultaneously offering them bribes to defect. With Guiscard's death in 1085, the Normans departed allowing the Byzantines to recover all their lost territory. Alexios had learned a valuable lesson from the Normans; his army needed time to be rebuilt, and until then success depended on diplomacy and intrigue. Fortunately for the empire, as he would prove again and again, in the 11th-century there was no better. In 1090, the Turkic Pechenegs crossed the Danube to raid Byzantine Trace once again. Alexios overcame this crisis by allying with a rival nomadic group, the Cumans, and together they crushed the Pechenegs at the Battle of Levounion (April 1091). When the Cumans then became over-ambitious, Alexios found a disgruntled group of Cumans, and bribed them to assassinate their chieftain. The message to Byzantium's enemies was clear; invade the empire at your peril, and leave no rivals in your wake for Alexios to exploit. After thirteen years on the throne, Alexios could finally turn his attention to Anatolia, where the situation had changed dramatically. Upon the death of the third Seljuq Suntan, Malikshāh I (d. 1092), the empire fell into chaos, as rival successors and regional governors carved up the state, and waged war against one another. This seemed just the opportunity that Alexios had been looking for to reclaim the empire's lost territory. But he still lacked the troops to go on the offensive. Always looking for possible allies, Alexios had worked dillegently to repair relations with the Papacy. In 1095, he wrote a fateful letter to Pope Urban II asking for Western support. The help he sought was simply some mercenary forces; what he got was the First Crusaders.

First Crusade[]

Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont from the Livre des Passages d'Outre-mer, c 1474. The council witnessed the pope's historic call for the First Crusade to capture Jerusalem for Christendom from its Muslim "occupiers".

When Emperor Alexios appealed to the Papacy for help, he perhaps failed to appreciate the complicated political situation in Latin Christendom at the time. By the late-11th-century, Western Europe's population, prosperity, and self-confidence were growing. It now possessed the capability to plan and carry through major military expeditions, as evident from the Norman conquest of England in 1066. At the same time, royal authority was weak in many parts of the continent, plagued by ambitious and prickly feudal lords with little to do but fight among themselves. The Christian Church attempted to moderate their endemic warring. One of the best-known examples was the Peace of God movement in central-southern France from 968, which sought to restrict the depredations of local lords to certain days of the week and times of year. Another solution was for Europe's knights to turn their efforts outward towards enemies of Christianity. As early as 1063, Pope Alexander II (1061-73) sponsored an armed pilgrimage to support the Reconquista against Muslim Spain. At the same time, the reform-minded Papacy was embroiled in a protracted series of quarrels with secular rulers, to assert the independence of the Church. The power struggle between Church and State had begun in imperial Germany with the Investiture Controversy on 1076, and would continue in England and France into the 13th-century. For Pope Urban II (1088-99), Alexios' appeal for help was the perfect opportunity to enhance the prestige and secular power of the papacy, by placing a large number of fighting men under direct Church control. Urban may have even hoped that, by helping Byzantium in her time of need, he could heal the rift of the Great Schism of 1054, and perhaps even bring the Eastern Orthodox Church under papal primacy. On the first days of November 1095, at the Council of Clermont in southern France, Urban delivered what was probably the most effective speech of the entire Middle Ages. It is difficult to know what was actually said, because all the surviving accounts were written decades later and differ widely from one another. There seems to have been little mention of Emperor Alexios, and the goal was much bolder than recovering lost Byzantine territory; he instead summoned a righteous war against the Muslims, with the ultimate goal of recovering the Jerusalem for Christianity. The Pope's message was spiced-up with tales of how the Muslims brutally oppressed their fellow Christians in the East, and prevented Western pilgrims from reaching the sites of the Holy Land. Some historians would call this a pretext, rather than a justification. The Islamic world had always shown a remarkable tolerance to other religions, especially Christians and Jews as fellow "people of the book". Arabic sources mark clear that Christians often held high offices, and it was not uncommon for Muslim rulers to have Christian-born wives or mothers. Apart from paying a special Jizya tax, Christians were able to play a full role in the community, certainly more that Muslims or Jews could in Latin Christendom. And Western pilgrims were actively encouraged to visit the Holy Lands, since it benefited the local economy. It is true that fighting between the Sunni Seljuks and Shi'a Fatimids in the region had made the pilgrimage trails more difficult and dangerous in recent years.

Peter the Hermit and his People's Crusade. Despite the pope’s deliberate intentions to appeal specifically to knights, a number of unexpected bands of peasants and low-ranking knights set-off for Jerusalem on their own, spurred-on by the charismatic preacher.

It is clear that the response to his speech at Clermont was much greater than even the Pope Urban II had expected. According to one account, the enthusiastic crowd responded with cries of Deus vult! ("God wills it!"), and several prominent lords pledging themselves to the First Crusade on the spot. Soon it seemed that entire nations were on the move as Crusading fever swept Europe. At a local level, the religious fervour sparked violence against non-Christians even before leaving Europe. At the end of 1095 and beginning of 1096, there were attacked on Jewish communities in Germany and France, with notable massacres first at Speyer, and then with increasing ferocity in Worms, Mainz, Cologne, Trier, Metz, and Prague; forced to convert or die, many Jews chose death. This is often cited as a pivotal turning point in Jewish and Christian relations in the Middle Ages; anti-Semitic persecution increasingly became a feature of European life from the 12th-century. Throughout 1096, nobles and knights predominantly drawn from the French aristocracy "took the cross". The fervour and moral exaltation of the crusading movement was undoubtedly a genuine manifestation of Christianity. Men joined for the defence of the faith therefore pleasing to God, as well as for personal salvation with remission of sins offered to any who might die in the undertaking; in time, this idea would evolve into the system of Indulgences (buying a remission of time in Purgatory) that would so incense Martin Luthar in 1517. But that was only one side of the coin. It also provided a licence for the predatory appetites of the feudal military elites. Crusading warfare would offer loot and licence on a scale unavailable in Christendom’s domestic wars. They could spoil the pagans with clear consciences. "Christians are right, pagans are wrong", said the Song of Roland, and that probably sums up the average Crusader’s response to any qualms about what he was doing. The vast majority of warriors had far less glamorous motives, simply compelled to follow their feudal lords. In the end, more men would pauper themselves to fight for their faith, than got rich; travelling to the Holy Lands was afterall very expensive. Incidentally, the Church would dramitically increased its landholdings in this period by buying up feudal estates. Pope Urban sought an organised army of knights, under his papal legate Bishop Adhemar of Puy (d. 1098). He tried to forbid certain people (including women, monks, and the poor) from joining the Crusade, and made no effort to lift excommunications on several European kings and great nobles, who might hijack the movement. The flower of European chivalry, however, were not the first to undertake the arduous journey towards the Holy Land. Contrary to the Pope's wishes, several ill-disciplined bands of peasants and petty knights set off for Jerusalem, months before the planned departure in August 1096; commonly known as the People's Crusade (April-October 1096). The most famous of these was brought together by a remarkable popular preacher called Peter the Hermit (d. 1115). Peter's fledgling "army" arrived in Constantinople unharmed in August 1096, despite making few friends while crossing Hungary and Bulgaria by pillaging the countryside and robbing markets for food. An appalled Emperor Alexios urged the unruly mob to wait for the main body of Crusaders, but then hurriedly ferried all 30,000 across the Hellespont. In Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), what little discipline there had been quickly broke-down, as the Crusaders spurred each other on to move more boldly against the infidels. When they reached the edge of Seljuk held Nicaea, they immediately fell into an ambushed and were virtually wiped-out. About 3,000 found refuge in an abandoned castle and were eventually rescued by the Byzantines. Thus ended the sad and sorry tale of the People's Crusade, but this was not the end for Peter the Hermit himself; he survived and joined the official Crusader, but aside from a few rousing speeches played no significant role.

The main force of the First Crusade (1095–99) departed in August 1096 as Pope Urban directed. It consisted of four main armies that made their way to Constantinople separately from different regions of Europe; from Germany, northern France, southern France, and Norman Sicily. There was a huge cast of nobles among the leadership of the Crusade, including brothers of the kings of France and England, but the six men who would most shape the course were: Bishop Adhemar of Le Puy (d. 1098), the papal legate and spiritual leader; Raymond of Toulouse (d. 1105), one of the most powerful and wealthy nobles of France, who perhaps expected to be the leader alongside Adhemar; Bohemond of Taranto (d. 1111), a Norman from southern Italy who had fought the Byzantines several times with his father Robert Guiscard; Tancred de Hauteville (d. 1112), a nephew of Bohemond; Godfrey of Bouillon (d. 1100), the only major German noble, who had previously been an anti-papal ally of king-emperor Henry IV; and Baldwin of Boulogne (d. 1118), Godfrey's morally flexible younger brother. Except for some pillaging, the whole host met-up in Constantinople in spring 1097 without serious incident. The presence near the city-walls of a slightly hostile army, numbering perhaps 35,000 including 5,000 mounted knights, would have been daunting for any ruler, but Emperor Alexios handled the situation with shrewd diplomacy. As each contingent arrived, they were quartered outside Constantinople, allowing only small unarmed groups inside the city under escort. He met personally with each leader, and, through a careful mix of imperial splendor, costly gifts, and sabre-rattling, extracted from them oaths to restore to him any conquered territory that had belonged to the empire before the Turkish invasion. In return, Alexios promised to supply them with provisions. None took the oath willingly. Raymond of Toulouse swore only a lukewarm oath, to cause the empire no harm. Despite this, Raymond and Alexios became good friends, and Raymond remained the strongest defender of the emperor’s rights throughout the Crusade. Alexios probably had few illusions that the Crusaders keep to their promises; the oath had sprung to Bohemond's lips far too quickly to be trusted. But he had done what he could.

The Crusaders crossed into Anatolia in early 1097, accompanied by a Byzantine army and by Peter the Hermit. The first objective of their campaign was city of Nicaea, now the capital of the Seljuk successor state, the Sultanate of Rûm (1077–1308) under Kilij Arslan. At the time, Arslan and his army was campaigning in the east against a rival sultanate, and paid the Crusaders little heed, assuming it could be dealt with as easily as the People's Crusade. Arriving at Nicaea unmolested in mid-May, the city was subjected to a lengthy siege, with the Byzantine navy blockading resupply via Lake İznik. Arslan rushed back to Nicaea, but was driven back by the unexpectedly large crusader force. After five week, Turkish garrison, wanting to avoid a sack, secretly negotiated the surrender of the city to Emperor Alexios. There was some discontent amongst the Crusaders who were forbidden from looting the city. Alexios paid the Crusaders generously for their efforts from the Sultan's treasury, but, believing they could have had even more if they had captured Nicaea themselves, the already strained relations began to sour. At the end of June, the Crusaders left Nicaea and marched on through Anatolia toward Antioch, ignoring Alexios' advice to proceed along the southern coast route so they could be resupplied. In order to simplify the problem of supplies, the army split into two groups; one contingent led by the Normans, the other by the French. About a week after leaving Nicaea, Sultan Arslan ambushed the Normans, who had marched ahead of the French. At the Battle of Dorylaeum (July 1097), the Turks attacked in their usual style, with nimble mounted archers charging in, shooting their arrows, and quickly retreating before the Crusaders could counterattack. The Normans responded by deploying in a tight-knit defensive formation around their baggage train. Despite heavy losses, the Normans held-on for some five hours, until the French contingent arrived and launched a surprise attack on the Turkish rear, prompting Arslan to withdraw rather than face the combined Crusader army. The Crusaders marched on to Antioch, but the journey through the arid and mountainous interior was a desperate test of endurance. It took almost three months in the heat of the summer, with very little food and water, as Sultan Arslan resorted to scorched-earth tactics; most of their horses died. Even before reaching Antioch, Baldwin of Boulogne left the main Crusading army to carve-out a fiefdom for himself in the Holy Land; his wife, his only claim to European lands, had died at Dorylaeum. He eventually married the daughter of the Armenian Orthodox Christian ruler of Edessa, and probably assassinated his father-in-law to create the first of the Crusader States.

The Siege of Antioch, from a 15th-century miniature painting by Sébastien Mamerot. The Crusaders gained entry to Antioch after an eight-month siege.

It was a parched and exhausted Crusader army that finally arrived at Antioch in October 1097. One of the great cities of the eastern Mediterranean, Antioch was surrounded by an enormous circle of walls studded with more than 400 towers, built by the Byzantines after recovering the city in 969. The city was so large that the Crusaders did not have enough troops to fully surround it, so it remained partially resupplied throughout what proved a long and difficult siege. After a bitterly cold Syrian winter, the spring brought the threat of a Muslim relief army. Fortunately for the Crusaders, the Islamic world was so riven by divided that counter-offensives came sporadically, and with their own agendas. Damascus and Aleppo dispatched separate relief armies in December and February, that if they had been combined would probably have been victorious. In April, an embassy from Fatimid Egypt arrived, hoping to establish a peace with the Crusaders, who were afterall enemies of their own Seljuk enemies. As the siege went on, supplies dwindled, and one in seven Crusader was dying from starvation. With the situation seeming hopeless, people began to desert and return home, among them the French knight Stephen of Blois, the son-in-law of William the Conqueror. On his way home, Stephen met Emperor Alexios at the head of a Byzantine army marching to reinforce the siege, and convinced him that Antioch's cause was doomed. The emperor’s decision to turn back, however justified, was a diplomatic blunder. On hearing the news, Crusaders claimed that this was treachery, reason enough to break any obligation to return the city to him. Bohemond, meanwhile, proposed that the first to enter the city should have possession of it. The Norman had, in fact, already made secret contact with a discontented Armenian Christian guard called Firouz within Antioch. On the night of 3 June 1098, eight-months into the siege, Firouz allowed a small contingent of Crusaders led by Bohemond to scale the wall, and then open a nearby postern gate. The Crusaders flooded into the dozing city, and a massacre ensued, with thousands of Orthodox Christian civilians killed along with Muslims, unable to tell them apart; among them Firouz' own brother. The victory, however, was incomplete. A few days later, a third Muslim relief army from Mosul arrived at Antioch; the erstwhile besiegers were now the sieged in a city already short of supplies. Once again the situation seemed hopeless, until the Crusaders found themselves the beneficiaries of, what could be described as, if one were so inclined, a miracle. On 15 June, an otherwise insignificant priest from southern France claimed to have had visions of St. Andrew; the starving Crusaders were prone to visions and hallucinations. He began to dig in the Cathedral of Saint Peter, and produced the relic of the Holy Lance; the spear that had pierced Jesus' side as he hung on the cross during his crucifixion. Bishop Adhemar was skeptical, as he had seen the Holy Lance in Constantinople; indeed there was yet another relic claiming to be the Holy Lance in Vienna. However, most of the Crusaders took this as a divine sign that they would survive, and thus prepared for a final fight rather than surrender. On 28 June, the Crusaders sallied-out from the city-gates, carrying the Holy Lance before them. In a confused responce, the resulting battle outside the city-walls was brief and disastrous for the Turks; soon the defeated Muslims were in panicked retreat. Thus, Antioch was restored to Christian rule. As expected, Bohemond claimed the city as his own, though Adhemar and Raymond disagreed. The Crusaders remained in city for almost a year, violently disagreeing over the disposition of Antioch, and subduing the surrounding countryside for food and horses. Meanwhile plague broke out in the city taking many lives, including Bishop Adhemar, the spiritual leader of the Crusade. The bishop had been a wise counselor and a stabilising influence that the quarrelsome leadership could ill-afford to lose.

Capture of Jerusalem by the Crusaders, by Émile Signol 1847. The siege is notable for the mass slaughter of Muslims and Jews perpetrated by the Christian Crusaders, the single greatest atrocity of the entire period.

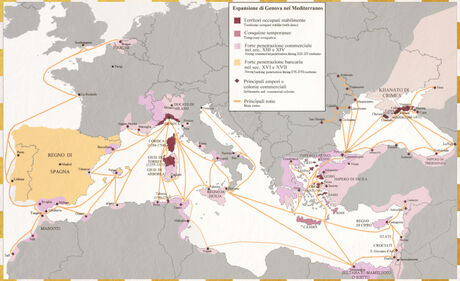

In January 1099, the minor knights became restless and threatened to continue to Jerusalem without their leaders. Raymond finally gave-in and the march restarted, leaving Bohemond behind as the first prince of the Crusader State of Antioch; he thus ignored both his oath to Alexios and his Crusading oath. Proceeding down the Mediterranean coast, the Crusaders entered Fatamid territory rather than Seljuk, and met little resistance, with their reputation for barbarity preceding them. Finally in June, the Crusaders reached Jerusalem, three long years after they had set out; many wept upon seeing the city. The governor was well-supplied and confident that he could withstand a siege until a relief force arrived from Egypt. The Crusaders, on the other hand, were reduced to less than 14,000 men. There was no hope of trying to besiege the city as they had at Antioch; the Crusaders resolved to take it by assault. On 8 July a strict fast was ordered, and, with the Muslims scoffing from the walls, the entire army marched in solemn procession around the city, and thence to the Mount of Olives, where Peter the Hermit preached with his former eloquence; apparently as instructed in a vision of Bishop Adhemar. The full assault on Jerusalem began on 13 July, with Raymond of Toulouse leading the attack on the southern part of the wall, and Godfrey of Bouillon positioning his forces on the north. After a day of little headway, Godfrey dismantled his siege towers during the night, and move them to a different part of the wall. The assault recommenced, and raged throughout the next day, into night, until Godfrey’s men finally took a sector of the walls and opened the nearest gate. On 15 July, the Crusaders flooded into the great city, and an most un-Christian slaughter ensued that has attained particular notoriety, as a "juxtaposition of extreme violence and anguished faith". Atrocities committed against civilians were normal in medieval warfare; the Christians had already done so at Antioch, as the Fatimids had done so themselves at Tyre in 996. However, the massacre of Jerusalem exceeded even these standards. The majority of the inhabitants were slaughtered, Muslims, Jews, men, women, and children; all the Orthodox Christians had been expelled before the siege. The only Muslims to escape were the city governor and his bodyguard, having surrendered the citadel in return for safe passage. The barbarism shocked even Christians, with Tancred de Hauteville giving his personal banner to a group of civilians, which should had assured their safety; they were killed anyway by other Crusaders. The eyewitness accounts of the Crusaders themselves leave little doubt that there was great slaughter, with one describing it as the "just and wonderful Judgement of God". It continued for at least two-day, which some historians see as suggesting deliberate policy rather than simple bloodlust; to remove the contamination of "paganism". How many people were killed is a matter of debate, but the city's population probably around 40,000. Capturing Jerusalem was a remarkable achievement, but holding onto it was going to take more fighting. Within a month, a large Egyptian army arrived to take back the city. However, the Crusaders marched out, and launched a surprise dawn attack, routing the over-confident and unprepared Muslims at the Battle of Ascalon (August 1099). Over several years, they were also able to secure control of the coastline with the aid of the Venetians and Genoese, who, as was customary, received extensive trading privileges; the port-cities of Acre, Beirut, Sidon, and Tyre was in Latin hands by 1124. From a modern perspective, the improbable success of the First Crusade is staggering. For medieval men and women, though, it was the work of God himself, who worked miracle after miracle for his faithful knights. It was this firm belief that would sustain centuries of Crusading.

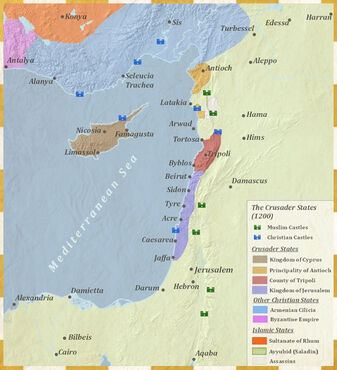

Crusader States[]

With the recovery of Jerusalem, attention soon turned to a problem of at least equal concern to many Crusaders; governing the newly conquered territories. The administration of the Crusader States (1098-1291) evolved over the next decade, settling into four feudal states. The most important was the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099-1187), extending from Beirut in the north almost to the Sinai Desert in the south. The Crusaders thwarted plans for the Holy City to be ruled under ecclesiastical authority, and Godfrey of Bouillon become its first king, over the claims of Raymond of Toulouse. The other three Crusader States were at least in theory vassals of Jerusalem: the Principality of Antioch (1098-1268), the County of Edessa (1098-1144), and finally the County of Tripoli (1109-1289), which was captured by Raymond's son after being outmaneuvered in Jerusalem. The European imposed their feudal system of governance on the region, with fiefdoms distributed to nobles and their followers in due degree. Castles were built at strategic or vulnerable points, among the most famous being Krak de Montréal and Krak des Chevaliers, tangible symbols of the dominance of a Latin Christian minority over a somewhat hostile majority population. The peoples of the Crusaders States were certainly cosmopolitan, with Latin, Orthodox, and Monophysite Christians, Sunni and Sh;ia Muslims, and Jews. Yet cross-cultural exchange, so fruitful in Spain and Norman Sicily, was decidedly lacking, with the Franks, as the locals called the Latin settlers, lording over the native population who lived like Western serfs. Only in medicine was there any willingness to learn from the infidel, as testified by the Crusaders who relied on Arab doctors on numerous occasions. The Crusader States survived far longer than might have been expected. Although surrounded by Muslim territory, they long benefitted from the chronic political and religious disunity amongst the rival rulers in Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo, Mosul, Konya, Diyarbakır, and Baghdad. Indeed, contemporary Arab chroniclers did not recognise the Crusaders as religiously motivated, assuming this was the latest phase in ebb and flow struggle with Byzantium. The Latin states presented an obstacle to Muslim trade with the Mediterranean and the land routes to the urban economy of Egypt. Yet this commerce not only continued but expanded, with spices, carpets, silk, dyes, sugar, and other eastern wares exported to Europe in unprecedented volumes. This may have occurred anyway, for Europe was growing wealthier, but the Crusades hastened the developments. The revenues of the Latin states were largely based on market tolls, while the Italian Maritime Republics of Venice, Pisa and Genoa grew rich through monopolising shipping and developed into Mediterranean powers. The Crusader States remained militarily weak and politically unstable throughout most of their existence. The nature of Crusades was unsuited to the defence of the Holy Land. Crusaders were on a personal pilgrimage and usually returned when it was completed, but the Crusader States needed large standing armies. Religious fervour was difficult to direct and control even though it enabled significant feats of military endeavour.

The Knights Templar, a religious military order of knighthood, founded in 1119 and active until about 1312. Their knights wore the famous white surcoat with a red cross, and a white mantle also with a red cross.

One of the main aims of the Crusade had been to enable pilgrims to reach the holy sites of Palestine. Protecting them from illness and attack was seen as an important task, which prompted the founding of several military-religious orders of knighthood, the most famous being the Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, and the later Teutonic Knights. The Knights Templar (1119-1312), or Poor Knights of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, were the earliest and most influential of the military orders. It was formed in 1119, when about nine French knights created a brotherhood who took monastic vows of piety, poverty, chastity, and obedience. They were granted a headquarters on the Temple Mount, below the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. The order was organized on a military basis, and relied on donations to survive. Their impoverished status did not last long. The Templars became a favoured charity throughout Christendom and grew rapidly in membership and power. Templar knights, in their distinctive white mantles with a red cross, made up as little as 10% of their members. Non-combatants managed feudal estates from Denmark to Spain, from Ireland to Armenia, as well as developing an early form of banking. With a reputation for honesty, Templar convents became a safe repository for cash, valuables, and important documents; people could make regular deposits like an modern bank account. They could even deposit money at one convent and, on showing a suitable letter, then withdraw equivalent money from a different convent; especially useful for the dangerous journey to the Holy Lands. At the peak of their power, the Templars had a network of nearly 1,000 convents and fortifications across Europe and the Holy Land, arguably forming the world's first multinational corporation. The Knights Hospitaller (1023-1798), or Knights of the Hospital of St, John, actually pre-dates the Templars as a religious order. In 1023, merchants from Amalfi in Italy were given permission by the Fatimid Caliph to build a hospial in Jerusalem to care for sick pilgrims. With the arrival of the Crusaders in 1099, the Hospital of St, John grew in importance and in wealth. Crusader knights, grateful to have their wounds healed, granted them land and revenues throughout the Holy Lands and beyond. The order never abandoned its original purpose, and, influenced by the Templars, they became a religious order that knights could join too. Like the Templars, the Hospitallers were some of the best-equipped, well-trained, and highly-disciplined soldiers in the Holy Land, and become an integral part of its defence, with castles of their own. Krak des Chevaliers acquired and extensively rebuilt by the Hospitallers in 1144, was the largest Crusader castle in the Holy Lands, and considered virtually impregnable. When the Holy Land was lost in 1291, support for both orders faded. Without the charitable function which nourishes the Hospitallers, the Templars were exposed to the temptations and jealousies of political life. Kings were also understandably wary of a serious challenge to royal authority from these elite knights who were a law unto themselves, answerable only to the pope. In 1312, Philip IV of France, with the pope in his pocked and an avaricious eye on their wealth, abruptly destroyed the Knights Templars, unjustly accused of heresy. The Knights Hospitaller faired better, capturing the island of Rhodes from the Byzantines in 1310, and ruling it until 1522, when they were driven-out by the Ottomans. The Hospitallers relocated to Malta as a Spanish vassal state, but the religious fervour of the Crusades had long since passed, and the order dwindled; still it soldiered on until Malta was captured by Napoleon in 1798. The Teutonic Knights (1191-1525) were formed much later and quite different from the Templars and Hospitaller. The main German contingent of the Third Crusade failed to reach the Holy Lands due to the untimely death of Frederick Barbarossa, but some German knights pressed on and assisted in the siege of Acre. A group of them form a fraternity similar to that of the Knights Hospitallers, with a hospital in Acre and a handful of castles around it. Their headquarters remained Acre until the city’s fall in 1291, but as early as 1211, German Teutonic Knights were diverting their energies to a different sort of Crusade; the Wendish Crusades against the pagan Slavs to the east of imperial Germany and the Baltic area. They eventually carved-out a vast feudal state for themselves, the State of the Teutonic Order (1226-1525), and played an important role in the emergence of Prussia.

Second Crusade[]

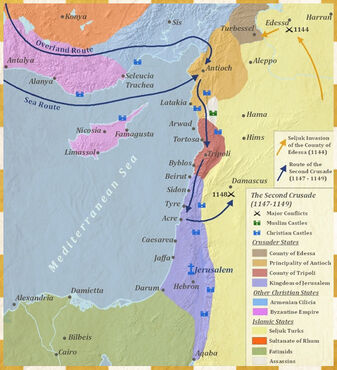

The Muslim reaction to the First Crusade began with the rise of Imad ad-Din Zengi (1127-46), the Sultan of Mosul. Despite his reputation as the first great champion of the Jihad ("holy war") against the Crusader States, he fought with equal enthusiasm against his Muslim neighbours. Not happy with only ruling Mosul, the ambitious Zengi immediately began to extend his power westwards, taking Muslim Aleppo in 1128. Two years later, Zengi allied with Muslim Damascus against the Crusaders, but this was a ruse; he had the sultan's son taken prisoner and extorted Hama from him, uniting three cities into a formidable sultanate. This new threat forced the Crusaders to form alliances with Muslim powers against their common enemy; when Zengi moved against Damascus itself in 1139, he was repelled with the help from Christian Jerusalem. From Aleppo, Zangi was well-placed to threaten the most exposed of the Crusader States, Edessa, which jutted-out into the Syrian desert. But this was not part of his plan until, in 1144, Edessa allied with the Muslim Diyarbakır, and marched almost their entire army on Aleppo. With the city defended, as a contemporary chronicler put it, "by shoemakers, weavers, silk-merchants, tailors, and priests", he hurried north to besiege the city, which fell in December 1144 after a four-week siege. Attempts at recovery failed, and the northernmost Latin state was lost.

It had long been apparent that Edessa was vulnerable, but its loss stunned Western Christendom. In 1145, Pope Eugenius III (d. 1153) issue a papal bull calling for the Second Crusade (1147-50). This was the first bull of its kind, which precisely worded the promised remission of sins for all those who took the cross, as well as ecclesiastical protection for their families and property. The Second Crusade, departing in summer 1147, had much more prestigious leadership than the First; two of Europe’s greatest kings. One army was taken east by Louis VII of France (1138-80), and another by Conrad III of imperial Germany (1138-52). Despite the royal seal of approval, the expedition was on all fronts a disaster. If the kings found it difficult to control their nobles at home, on campaign it proved next to impossible. When the German contingent reached Constantinople in September 1147, Emperor Manuel I Komnenos (1143-80) was not best pleased. The Crusade wreaked havoc with his foreign policy, which included an alliance with Germany, Venice, and the pope against the Norman Sicily, which had recently seized Byzantine Corfu. It was also complicated by a truce with the Sultanate of Rūm to secure Byzantine Anatolia. Although the Crusader States recognised the need for diplomacy with Muslim neighbours, Latin Christians from the West saw the Manuel’s move as confirming the duplicity of the Greeks. Nevertheless, the emperor adroitly managed the situation and ferried the Crusaders across the Hellespont without incident. Rejecting Manuel advise to follow the southern coast, in Byzantine rather the Muslim territory, Conrad marched across the arid and mountainous interior of Anatolia, having promised his men that they would be following in the footsteps of the First Crusade. Near Dorylaeum, not far from where the First Crusaders won their first victory, the weary army was set upon by the Turks and virtually destroyed; Conrad and a few survivors retreated to Nicaea, and eventually eventually reach Jerusalem by ship. Louis and his French contingent crossed the Hellespont in November, about a month after the Germans. He took the southern coast route, but it proved extremely harrowing. A small contingent of the German army had followed this route, pillaging all the way, and many of the Byzantine cities were unwilling to trade with the Crusaders. With supplies running short, and continually harassed from afar by the Turks, the French reached the port of Adalia, where Louis and his close associate decided to sail for Antioch. The rest of the army had to resume the long march, and were almost entirely destroyed, either by the Turks or by sickness. From Antioch, the Crusaders made their way to Jerusalem without major incident. Despite the losses already suffered by the Crusaders, it was possible to field an army of nearly 50,000 men, the largest Crusade army so far assembled. In June 1148, at a council to discuss how best to proceed, it was decided to attack Damascus. How this decision was reached has long perplexed historians; Damascus, fearful of the expanding power of Zengi, was the one Muslim city disposed to cooperating with the Franks. It well-illustrates the gradual divergence of interests between Crusaders who settled in the East, and Crusader armies from the West. The Crusaders States sought to secure their survival, and, if sound strategically, would make alliances with the Muslims; they had more in common with Byzantium in many ways. The Western Crusader armies were ideologically driven, seeking glory and plunder through spoiling the infidel, irrespective of the consequences; Damascus was simply a prestigious and wealthy prize. The Damascans now had little choice but to the call on their former enemy for aid, Zengi's son, Nur ad-Din Zengī (1146-74); Zengi himself had been assassinated by a slave a few months earlier. Not only was the Crusader campaign poorly conceived, but it was badly executed. After a four-day siege, with Nūr al-Dīn’s forces nearing the city, it became evident that the Crusader army was dangerously exposed, and a retreat was ordered. A new plan was made to besiege Muslim Ascalon (the gateway to Egypt), but Conrad and Louis had quarrelled at Damascus, and it came to nothing. With that, the Second Crusade fizzled-out, having accomplished almost nothing. It's only tangible success was helping the Portuguese capture of Lisbon from Muslim Spain, achieved by a group of English Crusaders whose ship stopped there en-route.

The loss of face for the French and German kings was considerable, but the damage done to the Crusaders' cause was greater still. The leaders inevitably looked for a scapegoat, with the blame unjustly heaped on Byzantium. Indeed, King Louis' resentment was so great that he openly accused the Emperor Manuel of colluding with Turks in Anatolia, and even agreed a plan with Roger II of Sicily for a new Crusade against Constantinople. Lacking papal support, the plan came to nothing, but the perception that the Byzantines were part of the problem rather than the solution became widespread in Europe. In the Holy Land, the Second Crusade had disastrous long-term consequences. The Muslims were enormously encouraged, having confronted a major Western expedition and triumphed. And the people of Damascus had now lost patience with the Christian kingdoms. When Nur ed-Din appeared below the city-walls in 1154, the population open the gates to his army. Thus, Damascus was annexed to Zengid territory, one more stage in the encirclement of the precarious Crusader States by a single Muslim power. All that was needed now was a unifying force, and this was provided by the West's greatest nemesis of the Crusading Age, Saladin.

Rise of Saladin[]

Sculpture of Saladin in the Egyptian Military museum in Cairo. Saladin’s skills in warfare and statecraft, as well as his personal qualities of generosity and chivalry, has resulted in him being eulogised by both Christian and Muslim writers.

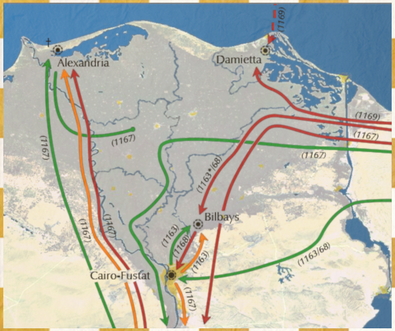

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub (d. 1193), known in the West as Saladin, remains a captivating figure even after strenuous efforts by skeptical historians to cut through the romantic image of the "chivalrous Saracen"; a man of his word and just in his dealings. Saladin's rise began under the tutelage of his uncle Shīrkūh (d. 1169), a prominent general in Nur ad-Din Zengī 's army, of Kurdish descent. In the 1160s, the possibility that the Shi'a Fāṭimid Egypt (909-1171), shaken by palace intrigues and assassinations, might collapse caused anxiety in both Syria and the Crusader States. At the height of its power, in the early-11th-century, Egypt was the centre of an empire that stretched from Tunisia to Palestine, from Sicily to Mecca and Medina. Cairo rivalled Constantinople as the economic powerhouse of the Mediterranean, linked as it was to the extensive Indian Ocean trade network that reached all the way to China under the Song Dynasty. The Fatimid focus on agriculture and industry further increased their riches; Egypt had been the bread-basket of the Roman Empire until lost to the Arabs in the 7th-century, while flax cloth and sugar were production on an industrial scale. Then, from the 1060s, the tentative balance between the Moorish, Turkish, and Sudanese elements of the Fatimid army collapsed into more than a decade of civil-war; the same ethnic conflict facilitated the Norman conquest of Sicily, as well as the rise of the Almoravid Sultanate in north-west Africa and later Spain. The Egyptian Caliphate was ultimately saved by a general of Armenian descent called Badr al-Jamali (d. 1094), but henceforth the Fatimid Caliph was a puppet of their military Sultans; much as the Seljuk Turks had dominated the Abbassid Caliphs of Baghdad. Any remaining power the Fatimids may have had was shattered when a 14-year-old youth succeeded as Caliph in 1149, prompting another period of instability that culminated four years later in the murder of almost all male members of the Fatimid royal family. Nur al-Din Zengī had long sought to intervene in Egypt, and in 1163 sent his reliable lieutenant Shīrkūh, accompanied by his nephew Saladin, to try and gain control of the country. In response, the Egyptian Sultan sought help from King Amalric of Jerusalem (d. 1174), one of its ablest rulers. After some maneuvering, the armies of both Shīrkūh and Amalric had to withdraw. In 1167, Nur ad-Din Zengī sent Shīrkūh back to Egypt, and the same happened. It was during this campaign that Saladid first showed his potential as a military leader, commanding the right wing at the Battle of al-Babein (March 1167), a tactical draw that prompted both armies to withdraw once again. Facing increasing internal pressures from his unpopular alliance with Amalric, the Egyptian Sultan opened negotiations with Nur al-Din to keep Shīrkūh from attacking Egypt for a third time, and thus provoked the culmination of this three-way struggle.

During King Amalric's reign, Jerusalem had become more closely allied with the Byzantine Empire; he married the niece of Emperor Manuel (d. 1180). In 1168, Amalric and Manuel joined forces, and invaded Egypt. A major turning point came when Amalric captured Bilbeis in early November, a city that had frustrated him on both his previous campaigns; he carried out an appalling massacre of the population. Having alienated the Egyptian population, Amalric's position quickly became unsustainable. When Nur ad-Din Zengī sent Shīrkūh and Saladid into Egypt for a third time in December 1168, they were welcomed, given money and provisions. Amalric immediately withdrew, allowing Shīrkūh to enter Cairo unopposed. The Fatimid Caliph now took matters into his own hands, arresting and executing his Sultan, and appointing Shīrkūh in his place. Nur ad-Din had seemingly accomplished his goal of uniting the Muslim states of Syria and Egypt. However, the situation was complicated by the death of Shīrkūh in February 1169, who was succeeded by his nephew Saladin; Nur ad-Din barely knew his loyal lieutenant's nephew, and soon came to distrust his ambitious underling. Few would have expected 32-year-old Saladin to retain power in Egypt for long; a foreign Sunni ruler of a state that had been unstable for decades, while under constant scrutiny from his overlord. Yet Saladin seemed to have a natural instinct for leadership, quickly gaining the reputation that would come to define his life and legacy; firm but fair, pious and devoid of pretense, generous and, when necessary, capable of breathtaking ruthlessness. Saladin almost immediately faced a revolt by the established pro-Fatimid military elites. He foiled a plot to have him assassinated, but the Cairo garrison rose in general revolt. However, Saladin quickly and effectively put down this insurrection. All the garrison's families lived in one particular suburb of the city; he ordered it to be set on fire. Afterwards, he began restructuring the Egyptian military around the Syrian units that had remained with him in Egypt, making it more effective and loyal; he also appointed his relatives to important positions throughout the government. This was not Saladin's only early test. In October 1169, Amalric of Jerusalem invaded Egypt for a fourth time, in alliance with the Byzantines once again. The joint force besieged the port-city of Damietta, by land and sea, but Saladin was well-prepared and the city held-out until famine broke out in the Christian camp; each side blamed the other for the failed campaign. This military triumph over the Christians helped secure Saladin's hold on Egypt.

Nur ad-Din Zengī gradually realized that he had created a dangerous rival in Saladin. Clearly feeling secure in Egypt, Saladin campaigned against the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1170. However, when Nur ad-Din planned a joint attack the next year, Saladin withdrew early from the campaign, probably preferring the Crusader kingdom as buffer between Egypt and Syria. In order to reign in his ambitious underlings, Nur ad-Din ordered Saladin to depose the Fatimid Caliph, reconciling Shi'a Egypt with the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad. Saladin stalled for months but eventually did obey, when the Caliph fortuitously fell ill and died; or perhaps was poisoned. Tension continued to mount, especially over the size of Saladin's tribute payments, and Nur ad-Din was on the verge of invading Egypt, when he fell suddenly ill and died in May 1174. He was succeeded by his 11-year-old son, as-Salih Ismail (d. 1181). Without waiting to be invited, Saladin announced that the boy needed a strong regent, and declared himself his guardian. He marched on Damascus, where the city-gates were opened to him amid general acclaim; as-Salih, however, had been removed to Aleppo by a rival. Saladin then proceeded to reduce other cities that had belonged to Nur al-Din, through a potent mix of warfare and diplomacy. Without a Zengid prince to legitimise his claim to Syria, Saladin carefully cultivated him image as the defender of Sunni Orthodoxy against rival faiths, using his victory over the Amalric of Jerusalem and removal of the Shi'a Caliph in Cairo to give his claim weight. After his victory over an army from Aleppo at the Battle of the Horns of Hama (April 1175), the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad graciously welcomed Saladin's assumption of power, formally recognising him as Sultan of Egypt and Syria, as well as the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Unfortunately, there was personal risk in this, and he twice survived attempts on his life by the Nizari Ismailis sect; known in the West as the Assassins. This secretive Shi'a sect had emerged following the Sunni Seljuk conquest of Persia in the 1040s, and established a dozen fortresses in the Alborz Mountains, with their headquarters at the virtually impregnable Alamut Castle. Over the course of two centuries, they cause havoc in the Muslim world, killing at least two Caliphs, many Sultans, and quite a few Crusader leaders. In 1176, Saladin led his army into the Alborz Mountains, but strangely abandoned the campaign after a few weeks. According to legend, assassins stole into Saladin’s tent during the night, and, rather that killing him, left a warning pinned by a poisoned dagger beside the bed of the sleeping sultan. Like countless others, the Nizari Ismailis would eventually meet their match in the Mongols. Meanwhile, Aleppo and Nur ad-Din's son remained a serious thorn in Saladin’s side, but he still found time to clash with the Crusaders. He suffered defeat trying to recover the southern fortress of Ascalon ("the gateway to Egypt") in 1177, but was victorious in the Golan Heights in 1179, destroying a new border castle being built by the Knights Templar at Jacob's Ford on the River Jordan. Saladin’s position was greatly strengthened, when Nur ad-Din's son died of illness in 1181, and Aleppo finally fell to him two years later. A Zengid prince still ruled in Mosul, but Saladin shamed him into agreeing to a truce, stating "they are not content not to fight [the Crusaders], but they prevent those who can". Salidin had now made Nur ad-Din's dream a political reality, uniting Syria and Egypt into a single Muslim power, and completely surrounding the Crusader States. In the process, he had also recreate some of the same brotherhood, discipline, and religious zeal, that had seen the first generations of Muslims conquered half the known world.

Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, known to history as The Leper King, here depicted in the film Kingdom of Heaven. Baldwin, whose body was already ravaged by aggressive leprosy, personally fought in battle against Saladin at Montgisard in 1177.

Meanwhile in the Crusader State, King Amalric of Jerusalem (d. 1174) died just a few weeks after Nur ad-Din, leaving the kingdom to his 13-year-old son Baldwin IV (1174-85). By all accounts the boy had the makings of a fine king; quick-witted, charismatic, and a skilled horseman. Unfortunately, he suffered from leprosy, though this only became evident after his ascension to the throne; he fought with his sword in his left hand, since the right was completely numb. Despite the young king’s extraordinary fortitude, his precarious health necessitated a continuous regency council, which accentuated the political wranglings between two existing factions: the so-called "noble party", the old families of the kingdom led by Raymond of Tripoli (d. 1187), who sought feudal autonomy and to avoid unnecessary conflict with the Muslims; and the "court party" led by the king's mother, and generally consisting of recent arrivals from the West such as Guy of Lusignan (d. 1194) and Raynald of Châtillon (d. 1187), who favoured war with Saladin. As Baldwin was not expected to live long or have children, the focus of his succession passed to his sister Sibylla. The perfect spouse seemed to be found in William of Montferrat (d. 1177), a cousin of both Louis VII of France and of Frederick Barbarossa of Germany, bringing the possibility of external aid. Unfortunately, he died a few months into their marriage, leaving Sibylla widowed and pregnant with the future Baldwin V. In the end, the court party outmaneuvered their rivals, and Sibylla subsequently married Guy of Lusignan (1186–1192), a vane, weak, and foolish newcomer to the East. In the meanwhile, the Kingdom of Jerusalem had become increasingly lawless, exemplify by the activities of Raynald of Châtillon. Raynald had arrived in the Holy Land with the Second Crusade, and eventually became Duke of Antioch, through a fortuitous marriage. He was always in need of funds, and launched aggressive plundering raids against Muslim territory, that scandalised even his Christian contemporaries. In 1161, he was captured captured by the governor of Aleppo. His family seemed in no rush to raise a ransom, so he was held in prison for fifteen-years. On his release in 1176. his stepson was firmly established as ruler of Antioch, so Raynald made his way to Jerusalem determined to restore his prestige and fortune, as well as revenge himself on his former captors. Another fortuitous marriage in 1177 gained him the modest fiefdom of Hebron, conveniently located near the caravan routes between Egypt and Syria. He was one of the only Christian leader to pursue an offensive policy against Saladin, making plundering raids against the caravans travelling near his domains. In his most audacious raid in early 1183, Raynald built a fleet of five ships, transported them overland to the Red Sea, and plundered his way down the Muslim pilgrimage route towards Mecca; an insult to Islam that Saladin pledged never to forgive. Despite growing tension between Saladin and the Crusaders, the peace generally held until Baldwin's death in 1185.

King Guy of Jerusalem surrendering to Saladin after the Battle of Hattin, one of the great victories of the celebrted sultan.

Baldwin IV had recognised the inadequacies of Guy of Lusignan, and, according to succession arrangements, Raymond of Tripoli became regent for Sibylla's young son, Baldwin IV of Jerusalem (1185-86). Unfortunately, the boy-king died within a year, and the court party orchestrated what was in effect a coup d’état, hastily crowning Sibylla, who in turn crowned her husband, Guy of Lusignan (1186-1192). With Jerusalem in a state bordering on civil war, the last thing it needed was someone giving Saladin a pretext to declare his long-awaited Jihad ("holy war"). But that is precisely what Raynald of Châtillon did. In late 1186, he plundered a caravan making its way from Cairo to Damascus while a formal truce with Saladin was still in place; a popular myth that Saladin's sister was travelling with the caravan is almost certainly untrue. Saladin sent an envoys to King Guy, who accepted that the attack amounted to a breach of the truce, but was unable and unwilling to compel Raynald to make recompense. Saladin immediately began to muster his forces from across his vast territories, and declared war on the Kingdom of Jerusalem; he also swore he would kill Raynald. In June, he assembled the largest army he had ever commanded, numbering around 35,000, and crossed the Jordan River south of the Sea of Galilee. At the resulting Battle of the Horns of Hattin (July 1187), the Muslims were aided by a phenomenal lack of military good sense on the part of their enemy. Saladin decided to lure King Guy into inhospitable terrain, by blocking the main road to Tiberias and sending a small force to besiege the city, which fell within a day. At a Crusader war-council, Raymond of Tripoli initially persuaded Guy not to fall into the trap. However, late that night, others changed the impressionable king's mind, accusing Raymond of cowardice. Having assembled almost every able-bodies fighting-man of the kingdom, Guy decided to risk everything on a single throw-of-the-dice. On 3 July, the Crusaders started out on the arduous journey across the Galilean mountains towards Tiberias, in mid-summer while harassed by Muslim horse-archers. With the slow progress, Guy decided that the army would not reach Tiberias by nightfall, but, with the Muslims blocking the route to nearby water-sources, was forced to pitch camp overnight on the arid plateau. Throughout an uncomfortable night, the Muslims harassed the demoralized, exhausted, and thirsty Crusaders, from their own well-supplied camp with a caravan of camels ferrying water from the Sea of Galilee. In the morning, as the march resumed towards Tiberias, Saladid order prepared piles of brushwood to be set alight and launched the bulk of his mounted archers at the Westerners, who were blinded by smoke. Although mounted elements of the Crusader army made repeated charges against the Muslim lines, only Raymond of Tripoli was able to broke through the encirclement, and Muslim horsemen carefully shepherded him away from the battlefield; he was one of the few Crusader leaders not killed or captured; it was later suggested that Raymond had been allowed to leave by prior arrangement, such was the mistrust between the squabbling Latin nobles. Without Raymond's forces, Guy's position was now even more desperate, and all discipline collapsed. The Crusaders were surrounded and, despite ferocious resistance, overwhelmed from all sides.Salidin's victory was total; every knight was slain or captured, except for Raymond and a few others. In one of the most iconic images of the Crudading Age, King Guy of Jerusalem and Raynald of Châtillon were brought to Saladin's tent. Saladin handed Guy a goblet of water, a sign in Muslim culture that the prisoner would be spared. Guy then passed the goblet to Raynald, but Saladin struck it from his hands, stating "You gave the man the drink, not I". He then charged Raynald with breaking the truce, and beheaded him with a single stroke of his sword. The king and other nobles were treated honourably and most were later ransomed, though any Templar and Hospitaller Knights were executed as Saladin feared their fighting skill and devotion to the Christian cause. To make matters worse, Saladin captured the relic of the True Cross, which despite efforts to retrieve it by Richard the Lionheart and others, the cross was never returned and eventually lost to history.

The surrender of Jerusalem on 2 October 1187, a devastating blow to the whole Crusading movement, and the event that provoked the Third Crusade.

King Guy had denuded most of the garrisons across Jerusalem to fight at Hattin, leaving the kingdom virtually defenceless. Over the next two-months, Saladin followed up his victory by occupying most of the major strongholds in the kingdom, with barely any fighting and limited plundering; he wanted to conquer a functioning kingdom. All the heavily fortified ports south of Tripoli fell one by one, including Acre, Jaffa (Tel Aviv), and Beirut. Only Tyre repulsed Saladin's siege, thanks to the fortuitous arrival of Conrad of Montferrat (d. 1192) on pilgrimage. Some historians view this as one of Saladin's few strategic blunders as it provided a bridgehead for the Third Crusade. On 20 September 1187, Saladin turned to the greatest prize of all; the Holy City of Jerusalem. Wanting to avoid bloodshed, Saladin offered generous terms of surrender, but those inside threatened to destroy the city rather than hand it over. There were only a handful of full knights in the whole city under Balian of Ibelin (d. 1193), but the city resisted assaults for nine-days, until Muslim's miners brought down a portion of the walls. With the situation hopeless, Balian rode out to negotiate the surrender of the city. Saladin's lasting reputation among Christians as a man of chivalry and honour derives above all from his treatment of the inhabitants of Jerusalem. The contrast, eighty-eight years earlier, with the behaviour of the First Crusade could not be greater. Instead of massacre, looting, and destruction, there was an orderly hand-over on 2 October 1187. A ransom was to be paid for each Christian to depart in freedom, but it was relatively small. The Christian authorities set an appalling example to the very end. The archbishop of Jerusalem, after buying his own freedom, departed with a wagon-load of the city’s treasures, rather than paying the ransom of poor Christians, who were probably sold into slavery; Saladin's brother and lieutenant, al-Adil Sayf ad-Din (d. 1218), was given a thousand of them and then set them free on the spot. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was allowed to remain in Christian hands, while Jews and Orthodox Christian were invited to resettle in the city; Latin Christians pilgrim were allowed to enter upon paying a fee.

Third Crusade[]

Upon hearing the news of the fall of Jerusalem, Pope Urban III (d. 1187) is said to have died of shock. His successor, Pope Gregory VIII (d. 1187), only reigned for a few months, but made his mark on history by issuing a papal bull calling for the Third Crusade (1189–92). Again the stakes were raised. Instead of the two kings who had led the Second Crusade, this time there were to be three: Frederick Barbarossa of Germany (d. 1122), Richard "the Lionheart" of England (d. 1199), and Philip II of France (d. 1223). The first rule to mobilise was Frederick Barbarossa, now nearly 70-years-old and approaching the end of an eventful reign. He set out by land for the East, in May 1189, with the largest army ever to march on a Crusade; about 100,000 in all. The last thing the Byzantine Emperor Isaac II Angelos (1185-95) needed or was capable of handling was a large Western army passing through his territory. After the death of Emperor Manuel (d. 1180), dynastic instability returned to the empire, in large part cause by growing tension with the West, especially the power and arrogance of Venice. Frederick Barbarossa had been openly hostile to Byzantium throughout his reign, refusing to honour his father's agreement for a joint campaign against Norman Sicily, and supporting separatist movements in Byzantine Bulgaria and Serbia. Meanwhile, the Crusaders were deeply suspicious of a treaty that Isaac II had made with Saladin, who promised to help curb Turks power in Anatolia. Isaac II could hardly have handled this volatile situation worse. He first granted the German army permission to cross his territory, but then panicked and threw every impediment in its way, perhaps fearful that Frederick intended to conquer Constantinople itself. But if he thought to intimidate Frederick Barbarossa, he had disastrously under-estimated the man. This was no disunited collection of Crusaders squabbling amongst themselves, but a powerful, well-disciplined army led by a decisive commander, who was not amused. In retaliation, he occupied Byzantine Adrianople, until Isaac II gave-in and transport them across the Hellespont as quickly as possible. In Anatolia, Frederick Barbarossa swept all before him, even sacking Iconium, the capital of the Sultanate of Rûm. Yet he would never see the Holy Lands. While impatiently fording the River Saleph, Frederick Barbarossa's horse slipped, throwing him into the water, where he drowned. With this, the vast majority of the massive German army aimlessly drifted home for the election of a new king-emperor; a small remnant under Leopold of Austria (d. 1194) did reach the Holy Lands. For Saladin, seriously alarmed by Frederick’s approach, the emperor's death must have seemed like act of God. For Isaac, he had achieved his goal of curbing Turks power in Anatolia, but at the cost of antagonising the West unnecessarily, and apparently confirming their long-held suspicions of Greek duplicity.

The fall of the port-city of Acre to the Crusaders was not a military disaster for Saladin. However, the loss of some seventy Muslim warship in the harbour, would decisively shift the balance of power in the eastern Mediterranean towards the Latin Christians.