| World War II | |

| Period | Late Modern Ages |

| Dates | 1939-1945 AD |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by Rise of Adolf Hitler |

Followed by Outbreak of the Cold War |

| “ | I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart. | ” |

–Anne Frank | ||

World War II lasted from about 1939 AD until 1945 AD. It began with the invasion of Poland by Nazi German in August 1939. It then ended with the dropping of the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the surrender of Japan in August 1945.

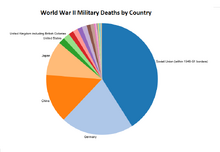

To this day, World War II remains the most geographically widespread military conflict the world has ever seen. It involved over 30 countries including all of the great powers formed in two opposing military alliances: the Axis including Germany, Italy, and Japan; and the Allies with France, Britain, the Soviet Union, the United States, and to a lesser extent China. The war was also the deadliest conflict in human history, marked by 40 million fatalities, including the deliberate genocide of The Holocaust, strategic bombing, starvation and disease, and the first use of nuclear weapons. World War I led inexorably to World War II, but World War II conclusively ended that chapter of geopolitical history. This great watersheds of 20th-century marked the decisive shift of power in the world away from the states of Western Europe and toward the rival superpowers of the United States and the Soviet Union, setting the stage for the Cold War.

History[]

Outbreak of WW2[]

In the aftermath of Germany’s annexation of Austria and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, Poland found herself confronted by an Adolf Hitler increasing day-by-day in confidence. The settlement reached for the German-Poland border at the end of World War I was probably unworkable at the best of times. The German territory of East Prussia was separated from the bulk of Germany by a narrow strip of land known as Polish Corridor, linking Poland to the Baltic Sea at the great port of Danzig, a semi-autonomous city-state. Meanwhile, Danzig, which had at different times in history been part of Poland and Germany, was almost entirely German-speaking, and from the mid-1930s had elected a Nazi city-council. Hitler’s demands to bring a strip of land within the German Reich, linking East Prussia including Danzig, were firmly rejected by the Polish government. Poland’s stance won a positive response from the Western powers, and in March 1939, Britain and France signed a mutual defensive pack guaranteeing Polish independence.

German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop (left) with Josef Stalin and his Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov (right).

Hitler intended to invade Poland anyway, but it was important to his plans that he should not be distracted by a major war on his eastern front. In August, he produced a diplomatic bombshell; the German–Soviet Non-aggression Pact (August 1939). The Soviet Union and Communism in general had long been the twin targets of Hitler's most vitriolic oratory. He now proved himself happy to set this aside for a very real strategic advantage, opening negotiations with Joseph Stalin with eastern Poland as the bait. With the Allied powers offering only a costly war against Germany for no very evident benefit, the Russian dictator took little time to decide. To the astonishment of the world, the two implacable enemies signed a nonaggression pact, with a secret clause for the partition of Poland between Germany and Russia, not dissimilar to the one that took place towards the end of the 18th century.

With this much achieved, Hitler launched a grisly little charade to justify the invasion of Poland for propaganda purposes. On 31 August, a group of German soldiers dressed as Poles attacked the German radio station in the border town of Gleiwitz, leaving the corpse of a prisoner taken from a concentration camp as evidence. In the early hours of 1 September, Berlin radio broadcasted to the world the news of this act of “Polish aggression”, and the German annexation of Poland was launched. Poland’s immensely long frontier was all too well suited for a demonstration of the new German theory of high-speed armoured warfare of Blitzkrieg, or “lightning war”. The tactics of short, fast, coordinated attacks were devised by the German General Staff based on their experience on the Eastern Front during World War I, where the war did not bog down into trench warfare; the General Staff continued covertly throughout the interwar years disguised as an administrative body. The Blitzkrieg began with heavy air strikes followed by a rapidly advancing ground invasion. The Polish army, airforce and civilian population put up a brave resistance to massive German forces, that were soon augmented by a Russian invasion from the east. By 28 September with 85,000 Polish soldiers and civilians dead, Warsaw fell. Poland was once again partitioned. Meanwhile, after a final desperate day of diplomacy, Britain and France had both declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939. World War II (1939-45) had begun.

Opening Hostilities[]

The New York Time of 1 September 1939

In the immediate aftermath of their declaration of war, neither France nor Britain took any significant actions for several months, aside from limited conscription. The French rushed troops to the virtually impregnable Maginot Line, an elaborate complex of concrete fortifications connected by underground railway lines, which has been constructed along the Franco-German border between 1929 and 1938. As in World War I, France’s border with Belgium was recognised as the weakest, and a British expeditionary force was immediately sent across the Channel to dig in along this line. From their own experience in the last war, it was generally accepted by France and Britain of the superiority of a defensive strategy. Germany likewise took little action after the invasion of Poland was complete, aside from several small naval attacks on Allied shipping. The U-boats were immediately deployed to demonstrate that Britain could no longer rely on her famed mastery of the seas; more than 100 vessels were sunk in the first four months. Hitler also had a devastating new weapon to unveil; magnetic mines dropped into the sea from the air to cling indiscriminately to a passing vessel and explode. Nevertheless, the lack of action led the news media in Britain and France to sarcastically label it a Phony War, as they waited for the expected German attack on Belgium and France. It would not come for eight months, until May 1940.

A Finnish machine gun crew during the Winter War

Meanwhile Stalin, assured of a free hand by Hitler, sent troops across the border into Finland in November 1939; the Winter War. Though vastly outnumbered and outgunned, the Finns resisted with magnificent resolve, and the Soviet losses were more than twice those of Finland. Yet by March 1940, Finland finally capitulated and ceded territory to the Soviet Union. In April 1940, the French and British finally agreed to launch their first joint offensive to neutral Norway, to cut-off the supply of iron-ore to Germany as well as access to the Norwegian sea-lanes. However, they delayed putting the plan into action too long. By the time they arrived, the Germans had already invaded Norway, and despite strong resistance seized all the important ports and dug-in defensively. The British and French arrived too late, and little was achieved. At the same time as the attack on Norway, Germany also quickly overran Denmark to safeguard their communications with Scandinavia.

Winston Churchill in December 1941 by Yousuf Karsh.

The military fiasco in Norway heightened dissatisfaction in Britain with Neville Chamberlain's conduct of the war. During the parliamentary debate to form a new all-party government, he was berated by a member of his own party reviving Cromwell’s famous words: “You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing... In the name of God, go!” When the Labour Party refused to serve under Chamberlain in the all-party government, he was replaced by a controversial figure as prime minister. Winston Churchill, after a brilliant career as a soldier and several high cabinet roles, had been sidelined throughout the 1930s because of his implacable opposition to Appeasement. Pugnacious and inspirational, Churchill would prove himself the ideal man for the crisis now facing Europe.

Battle of the Low Countries and France[]

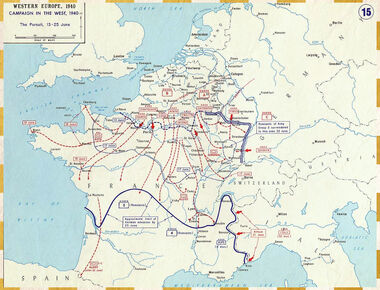

The Phony War ended in May 1940 with the most dramatic demonstration of the Blitzkrieg. While it had first been used with devastating effect in Poland, on the western front the defending forces were stronger, and the terrain of rivers and canals more difficult. Thus the speed of success and the range of offensive tactics were even more astonishing.

On 10 May 1940, German tanks of Army Group B crossed the border into the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium, while further south Army Group C held the French forces on the Maginot line. German paratroopers landed to seize strategic bridges, while 29 divisions of armoured corps and infantry moved at unimagined speed to separate the defending forces. In the Netherlands, after two days a German division reached the coast near Rotterdam, after three the government flew into exile in England, and after four the caretaker government surrendered to the invaders. In Belgium, with more significant French and British support, the agony lasted a little longer; eighteen days. On 14 May, the German advance was briefly checked at the Allied defensive Dyle Line, but at the same time a development in the centre made it almost irrelevant.

German soldiers remove obstructions to their tanks as they cross the Ardennes in Belgium

In a calculated gamble, an even large unexpected Germany offensive by Army Group A of 45 divisions drove through Luxembourg and the supposedly impenetrable Ardennes Forest; the Germans were throwing everything they had into this campaign, out of a desperate need for a breakthrough. While the forest provided excellent cover, the slow moving columns would be a sitting target if spotted; it fact they were spotted by French aircrews, but the reconnaissance was not acted upon. On 12 May, the second German offensive emerged from the Ardennes at the Meuse River. The French did try to reinforce the Meuse sector with reserve divisions, but crucially they lacked anti-aircraft artillery or anti-tank mines. While a thousand German aircraft carpet bombed the defenders into submission, the German infantry crossed the river in inflatables to establish three bridgeheads, allowing the tanks to be safely ferried across. The German army had punched a hole in the Allied defences between the Maginot and Dyle lines, into the open country of France. As they began pouring through in great numbers, on 20 May the Germans reached Abbeville in Northern France and the coast, cutting off the best part of the French army and thousands of British troops in Belgium, as well as the bulk of their tanks and artillery.

Troops evacuated from Dunkirk on a destroyer about to berth at Dover, 31 May 1940

In these desperate circumstances, the admiralty enlisted the help of every small craft in southern England capable of crossing the Channel; the Dunkirk Evacuation (26 May-4 June). Yet to reach Dunkirk in northern France, the Allied army had to cross the German occupied Belgium border. The miracle of Dunkirk would not have happened, but for an intervention by Hitler himself, who ordered the German army to hold back. His reasons remain unclear. It may be that he felt Britain would be less likely to make peace if humiliated by the capture of so many troops, or to safeguard his army for the more important offensive on France, or a mistaken assurance from Hermann Göring that his Luftwaffe could destroy the trapped Allied troops. Thus, the British and French made it to Dunkirk, and on 26 May the first troops embarked on the most improbable of flotillas of some 860 fishing smacks and private cruisers. For ten days, under a hail of German bombers, vessels plied back and forth with some 200,000 British and 140,000 French troops. It was not a victory, but a sensational avoidance of defeat, which Churchill greeted in pugnacious mood with his famous declaration: “We shall fight on the beaches ...”

For Hitler too it may not have been a victory, but he had his sights set on a bigger prize; the Battle of France (10 May-25 June 1940). On 5 June, the German army turned its full attention on France, with the Panzer division of Erwin Rommel in the vanguard, crossing the Seine just four days later. The psychological shock of the Allied losses in Belgium and the rapid German advance paralysed the French military command, and ate away all confidence in the French political establishment. On 14 June, the Germans entered a largely deserted Paris, with the French government having withdrawn to Bordeaux. Yet the Germans pressed on relentlessly, and by June 16 they were in the Rhone valley. Meanwhile, a similar drive southwards made the famous Maginot Line redundant, with the Germans sealing off the French divisions in these eastward-facing fortifications. Despite the Axis agreement, Mussolini had declined to commit Italy to the war until now, but this impressive sequence of events finally tempted him into the war. On 20 June, the Italian army crossed the south-eastern French border. Just two days later, France signed to an armistice with the German Axis powers. Why did the fall of France happen so fast? Contrary to the commonly myth, the French had a strong and vigorous army and airforce that was well matched in manpower and up-to-date military equipment. The main factor was the creativity and discipline of Germany’s generals, who brilliantly coordinated their army and airforces, and concentrated them at the critical moments of the campaign. They also benefitting from a great deal of luck. In contrast, the French supreme commander Maurice Gamelin relied on a defensive strategy without holding back significant and mobile reserves to rescue the crumbling defence. In World War I, French General Joseph Joffre responded to the opening German advance by calmly reorganised his forces in time to defeat the Germans at the Battle of the Marne (September 1914). France had no Joffre in May and June 1940.

Hitler tours Paris with architect Albert Speer (left) and sculptor Arno Breker (right), 23 June 1940

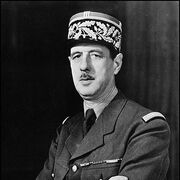

Mussolini had wildly ambitious plans for the armistice, but Hitler’s main concern was to ensure that the French would not go on fighting. He agreed to occupy only the northern two thirds of France already in the possession of his armies, as well as the tiny bit of south-eastern France which the Italian’s had captured. The French fleet and airforce were not even commandeered, insisting merely that they remain non-combatants; nevertheless much of the French fleet was subsequently destroyed by the British. However, if the terms of the armistice were calculated to minimise French humiliation, the signing was stage-managed with precisely the opposite intention. It was done in the precise place where Germany had signed the armistice that ended World War I, in the very same railway carriage which had to be retrieved from a Paris museum. He then travelled to Paris to see the famous sights; it was his first visit. The area left to France, officially neutral but in effect a German puppet state, became known as Vichy France. Yet France remained in the war in a different guise. Young brigadier general Charles de Gaulle, the undersecretary of war, had fled to Britain on 16 June. From there he became the symbol of French resistance, with his famous radio broadcasts to the people of France urging them to continue the fight; as well as frequently as something of a thorn in the side of Winston Churchill.

Battle of Britain[]

An iconic Battle of Britain photo, Spitfires from No. 610 Squadron based at Biggin Hill, Kent, fly over South East England

With the fate of France settled, Hitler turned his attention to the Battle of Britain (10 June-31 October 1940). His first task was to secure command-of-the-skies, to pave the way for an amphibious invasion dubbed Operation Sea Lion. The British were well aware that if the formidable German army set foot on British soil in large numbers, their army would quickly lose the war. During June, German bombing raids were launched against British convoys in the Channel, by 6 July as far inland as the barracks at Aldershot, and on 10 July seventy German bombers attacked docks in South Wales. These attacks were a major risk. The British planes were as good as their German equivalents, with even the newest and fastest Messerschmitt 109 equalled by Britain's Spitfire. Fighting over home territory also gave Britain some clear advantages: they were much closer to fuel supplies; and their pilots could bail-out with no fear of being captured and be flying again days later. Moreover, the British could tell when and where an attack was coming thanks to the world's most advanced application of the new technology of radar; a string of tall thin masts were constructed at intervals along the British coast from 1938.

The undamaged St Paul's Cathedral surrounded by smoke and bombed-out buildings and houses in December 1940

Even so, with German superiority in numbers, the dogfights and bombing raids of 1940 were indeed Britain’s darkest hour. Until August, the Luftwaffe targeted airfields and the radar masts. Sometimes as many as 1,500 German planes were involved in a single day. Yet, they lost more planes than the British, and had largely failed in their aim: the RAF was still very much intact and the radar masts stood. Nevertheless, RAF Fighter Command was under severe strain, and may have collapsed but for a change in German policy in September. From 24 August, British Bomber Command made five minor raids on Berlin, in response to German bombs accidentally dropped on a London suburb. Though they did little real damage, Hitler was incensed and insisted on a change of Luftwaffe policy to night-time bombing raids on large British cities, to destroy the nation’s infrastructure and demoralise the population. The first raid on London was on the night of 7 September. The Daily Express newspaper described it as “Blitz bombing”, treating it as part of Germany’s strategy of Blitzkrieg, and the name stuck. Throughout that winter, London and other major cities suffered the Blitz. Yet the change in Luftwaffe strategy eased the pressure on the RAF’s airfields, and proved the turning point in the battle. Moreover, the Blitz failed to break the British spirit, with Churchill making his famous speech to parliament: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” Of the Few, none deserve more credit than Air Marshall Hugh Dowding who devised and implemented the extremely well thought-out British defence system; though his tactics won the war, he was often disagreeable and was removed from command in November 1940. On 17 September 1940, Hitler decided to put his planned invasion of Britain on hold indefinitely, although bombing raids continued to terrorise British cities until May 1941; Germany had lost 1,700 planes to 900 British planes. Hitler’s plans to cross the Channel had always been somewhat half-hearted, out of an admiration of the British Empire as an Aryan people who had ruthlessly subjected millions of dark-skinned people to their rule, as well as concerns that Japan and the United States would gobble up the empire if defeated. The Battle of Britain was the first time in history that air-power alone decided the outcome of a major battle.

Other Fronts[]

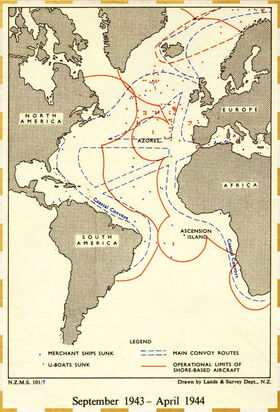

If Germany had failed to control the air, the outcome of the war at seas was yet to be decided. As in World War I, Germany’s best chance of starving Britain of supplies was through submarine warfare against merchant shipping in the Atlantic. On the very first day of the war, 3 September 1939, a German U-boat sank the British passenger-liner Athenia with the loss of 112 civilian lives. This was specifically contrary to Hitler’s order against targeting passenger vessels, remembering the damage done in May 1915 by the sinking of the Lusitania. However, the German U-boats also made an immediate impact on the military front, sinking the British carrier Courageous on 17 September with the loss of 518 lives. On 14 October, a U-boat achieved an even more sensational feat. Its captain, with great bravado, steered his way between the ships guarding the supposedly secure anchorage of Scapa Flow in Orkney, and torpedoed and sank the battleship Royal Oak killing 833 men. He then succeeded in evading his pursuers to arrive back in German waters, a hero. However, the main U-boat target was merchant ships carrying supplies, of which 114 were sunk before the end of 1939. With the fall of France in June 1940, Germany gained much more convenient home ports for her hunters, and a far greater range. For the rest of that year, the month-by-month tonnage of British ships sunk increased five-fold.

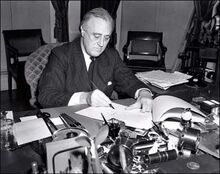

President Roosevelt signs the Lend-Lease bill to give aid to Britain and China (1941)

Meanwhile, October 1940 brought the first practical help from the United States. Britain received fifty antiquated but serviceable US destroyers, in exchange for the use of eight British ports in the western hemisphere. This allowed Britain to resort to the World War I solution of crossing the Atlantic in convoys with armed escorts. In March 1941, after much pressure from President Roosevelt, the US Congress found another way to help the beleaguered British. The Lend-Lease Act enabled the president to provide aid - food, oil, even warships and warplanes - to any nation whose defence he believed to be vital to American interests. In return, the US was given leases on naval bases in Allied territory. By the end of the war, Allied nations had received aid in value to some $50 billion. Churchill’s more urgent aim was to involve the United States as a combatant. The major obstacle was the strong isolationist streak among the American voters, though not shared by President Roosevelt himself, who was profoundly committed to an Allied victory. In July 1941, Roosevelt invited Churchill to cross the Atlantic for a secret conference. The two men had already established a warm personal relationship in correspondence over the past year, but they had not as yet met. The resulting Atlantic Charter was a very general statement of the basic principles of democracy, free trade and international law. Yet in one phrase, that the two leaders would together seek a peace which would “for ever cast down the Nazi tyranny”, the Charter made known to the American public and the world that there was no doubting where the United States stood.

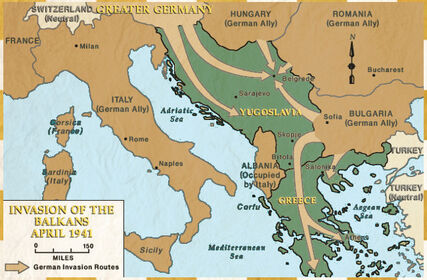

In October 1940, Mussolini, jealous of Hitler’s successes, ordered Italian troops across the Albanian border to invade Greece, a neutral country whose independence was guaranteed by Britain; unstable Albania had been annexed by Italy in April 1939. It would be the trigger for a great jostling for position among the countries of the Balkans still harbour many resentments from the past; the Balkan Campaign (October 1940-June 1941). Mussolini hoped for a swift success in Greece, a country of difficult mountainous terrain with a respectable army. Not only did the Greeks drive back the invaders, but they advanced into parts of Albania. The Greek accomplishments made Hitler realise that he would have to intervene to rescue his floundering ally, with some British aircraft now being sent to bases near Athens, whence they might attack German access to Romanian oil fields. He had already been busy forming alliances in the Balkans to secure his hold on Czechoslovakia; Hungary agreed an alliance in February 1939, Romania in November 1940, and Bulgaria in March 1941. In April 1941, German troops invaded neutral Yugoslavia, and within eleven days the country was overrun; Germany, Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria divided-up the territory between them. The German army then pressed on into Greece, where a small British force had also arrived in fulfilment of her guarantee. The country was occupied almost as rapidly as Yugoslavia; the British were driven from the mainland by the end of April, and from Crete a month later. Despite courageous resistance, the entire Balkan region was either allied with or occupied by German, and would remain so until 1944.

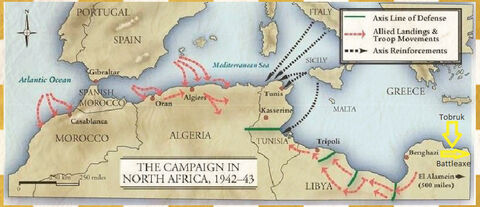

After the fall of France, the Allied position in north Africa was perilous. Britain had some 50,000 troops in Egypt and Sudan for the defence of the Suez Canal. Yet, the Italian had about 200,000 troops to the south in Eritrea and Ethiopia, and to the west some 300,000 in Libya. It looked easy for Mussolini to overwhelm Egypt, bringing great strategic advantage to the Axis powers. However, Archibald Wavell, the British commander in Egypt, took a boldly aggressive line against the superior forces and achieved astonishing results. From December 1940, the British moved armoured divisions fast through the desert in a series of surprise attacks on Libya, capturing the key coastal fortress of Tobruk, as well as large numbers of Italian soldiers and tanks. With the western threat eliminated, Wavell turned to the Italian colonies on the east African coast, taking Asmara in April and Addis Ababa in May, clearing the Italian threat out of both their recently acquired colonies.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel c.1942

The rapid British success in north Africa turned out to be merely the first in a series of see-saw reversals of fortune in north Africa over the next two years. Hitler realised that he must again extricate his incompetent ally, Mussolini, from another looming disaster. He put Erwin Rommel, the brilliant tank commander who had already distinguished himself in the summer of 1940 in France, in command of a small armoured force of two divisions being shipped to Libya. From March 1941, Rommel carried out the most prolonged feat of inspired generalship by any commander in the entire war, earning the nickname “Desert Fox” for frequently winning victories by tactical brilliance against far superior forces. By mid-April 1941, Rommel pushed the British out of Libya and back over the Egyptian border. In doing so he bypassed and isolated the British garrison in Tobruk. A much strengthened British and Commonwealth army pushed Rommel west again in November. During the winter of 1941-2 both sides received reinforcements. Rommel's strength remained considerably less than that of the Allies, but it was he who launches the next big campaign in May 1942, which brought him to within an ace of capturing Alexandria. In June 1942, Rommel succeeded at last in taking Tobruk, capturing 33,000 British soldiers and an immensely valuable supply of equipment and stores. By now the British were in full retreat, and by the end of the month Rommel reached El Alamein, 100 miles west of Alexandria. Yet, the exhausted and demoralized British troops managed to rally, and although they did not push Rommel back, but they halted his advance. Winston Churchill though was disappointed and used the occasion to change his general, with Bernard Montgomery becoming commander in Egypt; the beginning of a collision between two of the wars ablest commanders.

Invasion of Russia[]

By May 1941, after twenty months of war, almost everything had gone Hitler’s way. The nations of continental Europe were now either: allied to Germany like Italy and parts of the Balkans; neutral such as Vichy France, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal; or occupied by Germany like Austria, Czechoslovakia, most of Poland, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, most of France, and much of the Balkans. The only frustration had been the British, both the Battle of Britain and some successes by the Royal Navy such as the sinking of the magnificent new battleship Bismarck in May 1941.

The Soviet Union, the proselytizing force of world Communism, had long been the target of Hitler’s bitterest rhetoric. The German–Soviet Non-aggression Pact (August 1939) with Stalin had created the lull he needed to secure his western flank. With that behind him, Hitler was now ready to return to his grand strategy; an invasion of Russia whose vast territory would give the German master race the Lebensraum it needed. The betrayal of the German–Soviet Non-aggression Pact in 1941 is wholly intelligible only if Hitler’s political and racist ideology is borne in mind. The overthrow of the Soviet regime sooner or later remained his most profound emotional conviction, and he had become acutely paranoid of Stalin’s intentions. Meanwhile, the shambolic Winter War against the numerically inferior Finland seemed to confirm his belief that the Slavs were an inferior people that deserved to be subjugated. As early as the autumn of 1940, when the Battle of Britain was still raging, Hitler ordered plans to be prepared under the codename Operation Barbarossa. By this stage of the war, Hitler’s overall command of the military was absolute, yet while the invasion of Russia is now often considered Hitler’s greatest mistake, almost everyone in the German army seemed to believe it would be easy. His mistake, failing to learn the lesson of Napoleon's campaign, was to underestimate how long the operation would take, how hard the Russians would fight, how difficult it would be to control such a huge territory against successful partisan actions, and how poorly prepared the German military was for fighting in Russia’s climate. The ideological clash between the dictators of Fascist Germany and Communist Russian would see the war descend to new levels of barbarism on both sides.

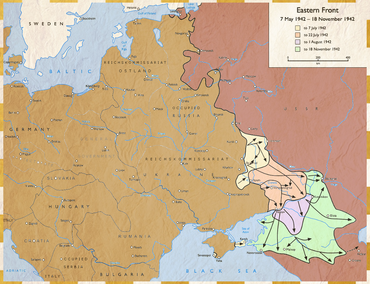

Hitler’s plans were to begin the campaign early in early May 1941, but precious weeks were lost due to the unforeseen Balkan campaign. It was not until 22 June that three army groups crossed the Russian border: in the north through the Baltic region toward Leningrad; in the centre toward Moscow; and in the south toward Kiev and the Black Sea coast. A gargantuan Axis force had been assembled of almost 4 million soldiers and 3,500 tanks, supported by 2,500 aircraft, spread across this 1,000 mile front. Much like Hitler’s previous invasions, the attack on the Soviet Union began by air and concentrated on Russian frontline airbases. The mostly obsolete Soviet airforce lost 1,200 aircraft on the first day and an additional 2,000 over the next week. At first it seemed that the army commanders would repeat their Blitzkrieg triumph of the west a year earlier. Stalin’s infamous purges of the 1930s had left the Soviet military leadership bereft of seasoned officers at all levels. After less than a week, in the centre the Germans reached Minsk 200 miles inside Russia, in the north in a remarkable coup they seize bridges on the River Dvina intact, and in the south, despite the stiffest resistance, they annihilated the last substantial Russian tank forces in the region; some 300,000 Russians had already been taken prisoner.

Yet even by the second week of the campaign there were signs that crushing the Soviet Union would not be quick. To the astonishment of German soldiers, encircled Russian forces near Minsk were fighting on even when their situation was plainly hopeless, mopping up was taking too long and costing too many German casualties, and despite taking some huge number of Russians prisoners, another 250,000 had escaped the nets and retreated. After less than four weeks on 16 July, in the centre the Germans were in Smolensk, 400 miles inside Russia and only 200 miles from the Russian capital. Yet the Russians were still fighting to the bitter end because their officers dared neither surrender nor retreat; in either case they would be executed by the Germans or by Stalin. At this point, at Hitler’s insistence, the focus of the German advance turned to the north and south. In the north, Leningrad, Russia's second city, was reached in August. Rather than storm the city, the Germans began bombing and starving it into submission; they hoped the siege would be over before the winter but it turned out to last for 900 days. In the south, in a disaster of staggering dimensions, 450,000 Russian soldiers were encircled near Kiev in September; just 15,000 escaped the carnage.

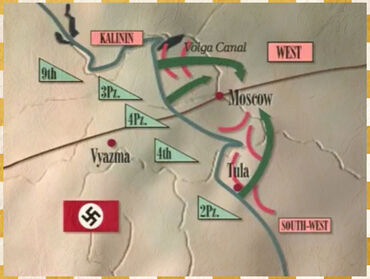

On 2 October, the German strategic offensive began on Moscow, named Operation Typhoon. The first Russian defensive lines at Bryansk and Vyazma were overrun by 10 October, yielding 600,000 Russian prisoners, bringing the tally since the start of the invasion to almost 3 million. Yet as the Russian winter started in earnest and the roads were reduced to quagmires, the advanced slowed to a snails-pace. In increasingly heavy falls of snow and ominously sinking temperatures, in early December the lead German Panzers stood less than 20 miles from the Kremlin. Yet the shivering German commanders and their men would learn the hidden strengths brought out in the Russians by depths of winter and extremes of danger. On 5 December, the Russians began their counter-offensive, using divisions brought from Siberia, and tanks and planes sent from Britain and the United States. They made progress, rolling the Germans back on some fronts as much as 150 miles.

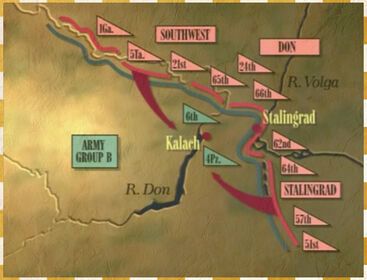

Yet in an astonishing feat of endurance in appalling conditions, the German resolve held firm, and when summer returned in 1942, the Germans were in place for a renewed offensive. This time the focus was to the south where Hitler had his eye on the oil fields of the Caucasus. Both Sebastopol on the Black Sea coast and Rostov at the mouth of the Don fell by July, but the third target Stalingrad proved elusive. It would become one of the deadliest single battles in history and lasted for six months. With extraordinary tenacity, fighting street by street, block by block, the Russians held the city against the initial German all-out assault. The city was gutted to a skeleton of its former self as the Germans launched repeated air raids involving as many as 1,000 planes at a time. On the ground, troops and tanks roamed awkwardly through rubble-strewn streets, and Russian and German snipers hid in the ruins and tried to pick off enemy soldiers. Stalin ordered thousands of additional troops to the north of Stalingrad, while the Germans surrounded the city from the west, trapping the Russian defenders inside the city. Yet the Germans were unable to gain control of the Volga River, and prevent resupply. Thus the Germans began a second winter on Russian soil, in the Blitzkrieg that had gone wrong.

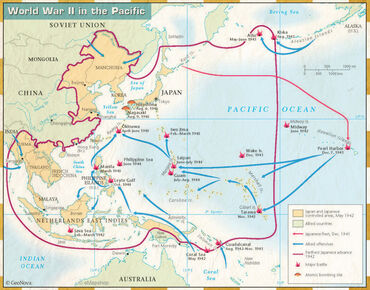

War in the Pacific[]

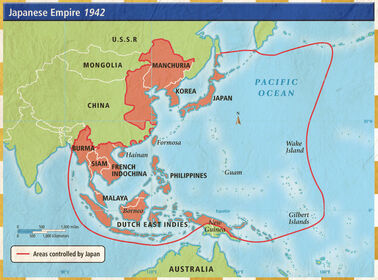

When the first Russian winter was bringing home the harsh reality of Hitler’s grand strategy, another great turning point of World War II was taking place without Hitler even being forewarned. War between Japan and the United States over the dominance over the Pacific had been a possibility ever since the 1920s, though tensions did not begin to grow serious until Japan withdrew from the Five-Power Treaty (1923) in 1934, when she sought naval parity with the United States and Britain, and was refused. She instead joined the German–Japanese–Italian Axis alliance in November 1936, on the basis of their shared animosity and fear of Russia. Until 1941, Japan had only been engaged in a regional conflict with China; the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45). With fighting in China having reached a stalemate, the fall of France to the rampant Germans in 1940, gave Japan the opportunity to occupy French Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) in September, in an effort to control supplies reaching China. Franklin D. Roosevelt, hoping economic pressure would end Japanese aggression in the East Asia, place a full trade embargo on Japan in July 1941, and froze her assets in the United States. With only two years of oil reserves, the Japanese were faced with the stark option of either severely curtailing their ambitions, or seize British Singapore and the Dutch East Indies to gain their own sources of oil and other raw materials.

USS Arizona during the attack

Thus, Japan entered World War II with a ruthlessness unmatched by any other combatant, and achieved in a few months a Blitzkrieg to rival anything achieved by Germany. It came literally out of a clear sky. In the early hours of 7 December 1941, nearly 400 Japanese planes took off from aircraft carriers in the mid-Pacific. Their target was the American fleet at anchor in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Taking the somewhat complacent Americans completely by surprise, all eight US battleships in the harbour were hit and five were sunk. Eleven other warships were sunk, and 188 planes were destroyed on the ground. More than 2,400 Americans died in the sudden attack. Japan had told their ally Adolf Hitler nothing of their planned attack on the United States, although he had long regarded American involvement in the war inevitable sooner or later. The Japanese were well aware that they could not win a long war against the United States, but they gambled on delivering a decisive victory in a short war that would bring the Americans to the negotiating table; as happened in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). Meanwhile, the attack on Pearl Harbor served to unify US public opinion in favour of entering World War II, and on 8 December Congress declared war on Japan with only one dissenting vote. Germany and the other Axis Powers promptly declared war on the United States, seeing the opportunity to attack Atlantic convoys without inhibition, and in the belief that Roosevelt would be too preoccupied with countering the Japanese advance in the Pacific.

Meanwhile, on the same day as Pearl Harbour, the Japanese launched air raids on American and British airfields in the Philippines, Guam, Midway, Hong Kong and Singapore, destroying numerous planes on the tarmac. It was a dramatic beginning to a campaign that for the next few months continued at the same intensity, by land, sea, and air. By Christmas, US Guam, Thailand, and British Hong Kong were easily taken. Before the end of January 1942, Sarawak, Brunei, and Malaya were in Japanese hands. February brought Bali, Timor, Amboina, and most shockingly British Singapore, after India the prize of the British Empire. In March, the Dutch surrendered Java. By the end of May, all Burma was in Japanese hands, a crucial lifeline for supplies to China. Together the German invasion of Russia and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour would have a decisive effect on the outcome of the war. The events add three major powers to the cast list of the world war against the Axis powers; the Soviet Union, the United States, and China, automatically now an ally of the Western powers.

The Holocaust[]

As more and more of Eastern Europe fell into German hands, a broad canvas was provided upon which Adolf Hitler was free to put into practice his vision of a new order, in which Germans will rule as a master race, inferior groups such as Slavs will be slave labour, and undesirables like Jews, Gypsies, and Communists will be exterminated. The appalling story unfolded in three separate stages.

Two Jewish women in occupied Paris wearing yellow badges in 1942

Before the outbreak of war, with Germany exposed to the eyes of the world, persecution of Hitler's hated groups was limited to intimidation and violence to terrifying them into moving elsewhere. By 1939, more than half the Jews in Germany as well as Austria had moved to other countries. With the outbreak of war and the closing of borders, occupied Western Europe also experienced the horrors of a police state and the anti-Semitic measures long familiar within Germany. Yet German rule here was less brutally repressive than in the east. The explanation lies in Hitler's vision of a united Europe. He believed the “Aryans” counties of the west, settled in the distant past by Germanic peoples such as Franks, Goths, Angles, Saxons and Vikings, would ultimately cooperate with his dream of a future that belonged not to a dominant nation, but a dominant race. By contrast the regions to the east of Germany, inhabited by the contemptible Slavs were suitable only for subjugation.

German police shooting women and children from the Mizocz Ghetto, 14 October 1942

With the invasion of Russia in June 1941, there was a sudden gear-change in German brutality. Hundreds-of-thousands of captured Russian soldiers were crowded into slave labour camps, surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, where they were neglect frequently saw them starve or freeze to death. In the wake of the invasion, the special task for the SS was to exterminate two particular groups of people; Communist officials and Jews. It was the true beginning of the Holocaust, a most deliberately planned attempt to exterminate the Jewish people, and a horror that far outstripped all others in the whole of world history. The work of the SS was carried out with ruthless efficiency. Victims were herded into open fields, forced to dig long pits, and then machine-gunned into their ready-made graves. In the city of Kishinev alone, in early July one such task force killed 10,000 people.

Entrance to Auschwitz Concentration Camp

Meanwhile, the Nazis were already working on a less visible and more efficient method of achieving their “final solution”. It was first employed at Chelmno in Poland during 1941, where three vans were specially adapted for the killing of people through exposure to lethal gas. During the first six months 97,000 Jews die in these vans. The scheme was considered highly successful, and steps were soon taken to provide larger-scale death camps with permanent buildings. These death camps were all built on Polish or Russian soil, as a practical measure of discretion by the Nazi high command. One of the first and largest was Treblinka in Poland where more than 750,000 Jews were killed from July 1942. It was taken for granted by now that the solution must apply to Jews of all the nations occupied by the Germans. Thus began one of the abiding images of the holocaust, trains of cattle trucks into which Jews from the west were crowded, heading for the Polish camps. In the first half of 1942 the prospect facing these people was immediate death, but during that year it occurred to the Nazis that they are wasting valuable slave labour. The trains would now be classified on arrival, as fit for labour or unfit; the unfit being the elderly and children. The first of these duel-purpose camps was Auschwitz in Poland which was ready for use in March 1942. Well in excess of a million people died in this camp in the next three years, possible nearly half of whom were judged fit but worked and starved to death. It is hard to know how much the German public were aware of the final stage of the Holocaust, though given that program of transporting Jews towards the east was quite public, it’s hard to imagine that they didn’t at least suspect.

Although the Jews were by far the largest group of victims with about 6 million, the Jews were not alone. Some 400,000 Gypsies were killed. Even “Aryans” were not immune from Hitler’s obsession with purity and perfection, with probably about 100,000 homosexuals and mentally and physically disabled people exterminated.

Resistance Movements[]

For any civilians living in an occupied country, resistance to the authorities was almost impossible, although the uprising in the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw in April 1943 that lasted nearly a month against vastly superior manpower and weapons, demonstrates how much that could be achieved by desperate people. The only turly effective form of resistance was to vanish into an underworld of secret cells of like-minded partisans who would undertake tasks to frustrate the enemy and hold down troops badly needed at the battlefront, from securing safe havens for hunted men, to acts of sabotage and guerrilla warfare. Each of the German-occupied countries had a resistance movement of this kind. Underground resistance was especially effective in the Soviet Union because of the ready-made political structure in place from the Communist police state and from functioning behind fronts on which the German armies were still engaged. Yugoslavia also had a very large resistance movement, where two rival movements developed; the Communists led by Josip Tito, and the Serbian nationalists. Competing with each other as much as against the Germans, they were already struggling for the future control of Yugoslavia. So were two similar groups in Greece.

De Gaulle during World War II

The help provided to the Normandy Landing makes the French Resistance particularly notable. There were many separate resistance movements in France, among whom the Communists were one of the strongest. However here an umbrella organization called the Marquis, promoted by Charles de Gaulle from London, did succeed in making the rivals cooperate. When the Allied invasion of occupied France finally occurred in June 1944, the Maquis would play a significant role in the interior carrying out acts of sabotage behind the German lines. After the German collapse, whole German units wandered around the French countryside desperately looking for Allied troops to whom they could surrender, to avoid the vengeful fury of the French Resistance.

Allies Gain Momentum[]

Japanese cruiser Mikuma shortly before sinking on 6 June 1942, the last day of the Battle of Midway

In the Pacific sphere, in mid-1942 the Japanese turned their attention to sinking the American aircraft carriers that had escaped destruction at Pearl Harbor, and what they hoped would be the decisive victory that would bring the Americans to the negotiating table. They chose as their target Midway Island, a coral atoll some 1,300 miles northwest of Hawaii which the United States was developing as an air and submarine base, with the aim to draw out the American fleet. In early June 1942, a large Japanese fleet including four of their largest aircraft carriers, moved towards Midway. The Americans, having solved the Japanese fleet codes, awaited them with their own carriers; the Battle of Midway (4-7 June). The battle from both sides was by planes launched at sea by dive-bombers and torpedo-bombers. Although the first American attacks were easily repulsed, some of them became lost, and now by luck they found the Japanese. The Japanese carriers were caught while refuelling and rearming their planes, making them especially vulnerable. The Americans sank all four of the Japanese aircraft carriers, along with 322 aircraft and over five thousand sailors. The Americans had losses too, including one carrier and one destroyer. But the Japanese fleet, suffering a major reverse for the first time in this war, sailed for home without even coming close to the mid-Pacific atoll. From now on, Japan’s struggle turned to maintaining the vast swathe of South-east Asia captured in the months after Pearl Harbor in the face of relentless American pressure.

In the east, the bitterly fought battle for the city of Stalingrad had seen some of the fiercest combat of the war. Yet neither side was able to gain absolute control of the city or evict the other, even though Germany's entire Sixth Army was involved. But the Germans, fighting far from their sources of supply, were unknowingly in the graver danger. In November 1942, a huge Russian counter-offensive was launched in two spearheads with the simple aim of encircling the Germans. Just four days later the noose was complete, though not yet tight. The city the Germans had been struggling so hard to occupy had become a trap with more than 200,000 German troops inside with food and supplies beginning to run out. The commander of the Sixth Army, well aware that this was the last possible chance to extricate his men, urged Hitler to allow him to break out of the encirclement, but the answer came back, no. In mid-January 1943, the commander in Stalingrad again protested to Hitler that it was beyond human strength to continue fighting in these circumstances. Again Hitler's reply was that not an inch of ground was to be given up. Thus on 31 January, Hitler was apoplectic when the commander and just 91,000 survivors surrendered to the Russians. The Battle of Stalingrad had cost about 1.1 million Russian lives, and more than 800,000 on the German side. After the battle, little of the city itself remained, and it would not be reconstructed fully for decades. It also marked the emergence of a group of younger and capable Soviet generals, chief among them Georgy Zhukov.

Montgomery in a Grant tank in North Africa, November 1942.

Meanwhile, the turning point in the war in north African campaign came when Rommel’s latest offensive against British Egypt was successfully driven back in August 1942. By now, Montgomery was commanding a force that outnumbered the Germans more than two to one. Eight weeks later the British were again on the offensive. Perhaps the most decisive battle in north Africa was the Battle of El-Alamein (October-November 1942) in which the German forces were defeated overwhelmingly; Rommel himself had been away on sick leave when the battle began and by the time he returned the situation was already hopeless. In the aftermath, he beat a retreat of 700 miles in two weeks so rapid and effectively that he left few prisoners or supplies in Allied hands. Meanwhile, within days of the British victory at El-Alamein, there was an entirely new element in the conflict. From the first German onslaught against Russia in June 1941, Joseph Stalin had been demanding that Churchill launch a second front to divert German troops from the east. Churchill even personally travelled to Moscow in August 1942 to persuade him face-to-face that a landing in France was not yet possible. But Stalin responded warmly to news of Operation Torch, the codename for the imminent invasion of north-western Africa. On 8 November 1942, under the overall command of Dwight D. Eisenhower, American forces carried out an amphibious landing on the coast of French Morocco and Algeria, in the first major participation by US troops. The invasion by more than 100,000 men at three fronts between Casablanca and Algiers posed an unprecedented dilemma for the 120,000 French soldiers loyal to Vichy France. There were three days of fighting before the French commanders told his troops to offer no further resistance. By then the situation in Vichy France itself had undergone a dramatic transformation. On 11 November, Hitler, in reaction to the Allied landings, abandoned the armistice agreement and sent troops over the border into Vichy France. At the same time Italian divisions invaded from the southeast. By the end of November, Vichy France was a German-occupied territory like any other.

With Rommel now caught between two far superior Allied forces east and west, a German withdrawal from north Africa seemed inevitable. Instead, Hitler, constitutionally unable to contemplate failure on the battlefield, decided to strengthen it with reinforcements shipped during the winter of 1942-3. By February, it looked as though Rommel may once again be able to work his magic. Making maximum use of surprise, he managed to first push west into Algeria against his American and French opposition. However, Allied pressure continued to mount with the British army in Egypt and Libya building up strength for a major push against the German lines in western Libya. From mid-March, the trap began to close. As the fighting continued well into the spring of 1943, Rommel’s forces fought with tenacity in one battle after another. Nonetheless, the Allies consistently gained. Finally on 7 May 1943, British armoured divisions reached and captured Tunis. On the same day, American and French forces took the nearby port of Bizerte, cutting off the escape of more than 250,000 German troops who were soon taken prisoner; Rommel himself had returned to Germany in March. With that, the long campaign in north Africa was over, a blow to Germany's military reputation and self-confidence. Meanwhile, Hitler’s obsessive refusal to yield had now lost him an entire German army in north Africa and another in Stalingrad.

The crucial Battle of the Atlantic was reaching its apex in 1943. The German production of bigger and faster U-boats, and the increase of her fleet to 240, resulted in a massive increase in the number of merchant ships sunk in the early months of 1943. March 1943 saw the climax of the U-boats’ good fortune, sinking 627,377 tons of shipping in a single month, including 21 ships in a single convoy attack. Yet the Allies had a new weapons in the pipeline; ships equipped with radar set to a very short wavelength undetectable to the U-boats. In April and May 1943, fifty-six U-boats were sunk in a regular offensive by long-range bombers. For the rest of the war, monthly totals were greatly reduced to less than 100,000 tons of Allied shipping. Just in time, victory in the Atlantic went to the Allies.

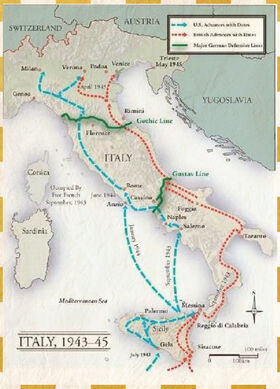

The capture of the German army in north Africa in May 1943 dramatically alters the balance of power in the Mediterranean. It also brought to an end the heroic endurance of the citizens of the tiny island of Malta. For over two-years, Italian and German airforces flew some 3,000 bombing raids against this British outpost, with food and fuel often only able to be delivered by submarine. In July, US and British forces under George Patton and Montgomery invaded Sicily using troops deployed by parachutes, gliders, and boats, and Palermo and the island fell to the Allies after two weeks; the first penetration of any Axis territory by the Allies. The Sicilian campaign had immediate repercussions in Italy. During the night of 24 July, Benito Mussolini was overthrown in a peaceful coup and placed under arrest. The new Italian government promptly began approaching the Allies about an armistice. On 8 September 1943, Italy accepted unconditional surrender, and three weeks later agreed to join the Allies. It was understood that Italy would be treated with leniency in direct proportion to the part that it would take in the war against her recent ally, Germany. One difficulty was that the Germans had meanwhile brought in reinforcements and soon established Italy as yet another client state. Hitler ordered a parachute raid by the SS to rescue Mussolini from prison, and appointed him puppet dictator of German-occupied Italy, no less a prisoner, for his palace had the SS guarding it. He would eventually be shot by Italian partisans in April 1945.

Thus even as negotiations took place with Italy, the Allied invasion of Italy proceeded as planned. The main invasion, by a multinational Allied force including US, British, Canadian, French and Polish troops, began the day of Italy’s surrender. The major landing took place at Salerno just south of the port of Naples, with smaller landings at the toe and heel of Italy. German resistance however proved very heavy, with the US forces in particular suffered great casualties. After slow and treacherous fighting, the Allies finally captured Naples on 1 October, putting all of southern Italy under Allied control. Yet, the shape of Italy, long and thin with a spinal range of mountains, was perfectly suited for defence, and the Italian campaign would prove long and arduous for the Allies. The Germans formed a defensive position called the Winter Line across the width of Italy, some 30 miles up the coast from Naples, with the fortified monastery of Monte Cassino in the centre. For six month, the Allied forces assaulted the entrenched Germans over and over again, and each time were pushed back, until Monte Cassino finally fell in May 1944. Rome was liberated shortly afterwards on 5 June, but the German resistance further north did not collapse as hoped. By the time Florence was taken ten week later, the Germans had established another strong defensive position called the Gothic Line stretching through the hilly country from Pisa to Rimini. The Allied advance ground to a halt again, this time until April 1945.

There was yet another front on which the advantage swung towards the Allies during 1943. In the Allied bombing of Germany, the technique of carpet bombing, pioneered by the Germans at Coventry, was turned upon them with a new intensity. From March to July 1943, Britain's Bomber Command mounted an almost nightly campaign against the industrial targets in the Ruhr. The assault on the Ruhr was followed by equally intense attacks on Hamburg from July to November 1943, and on Berlin from November 1943 to March 1944. The destruction was devastating, but as with the Battle of Britain, it failed to break the morale of the German people. More effective was the brilliantly ingenious raid on the hydroelectric scheme in the Ruhr valley, which were destroyed in May 1943 by the bouncing bombs of the Dam Busters.

Surrounding Germany[]

With the establishment of second fronts in Italy, in the Atlantic and in the air over Germany during 1943, Churchill accepted reluctantly that the planned invasion of Normandy codenamed Overlord cannot happen with any reasonable chance of success before the summer of 1944. Meanwhile with Russian advances in the east early in 1944, there were alarming signs of a race developing. Would Stalin's Communist forces or those of the capitalist West penetrate furthest into Germany?

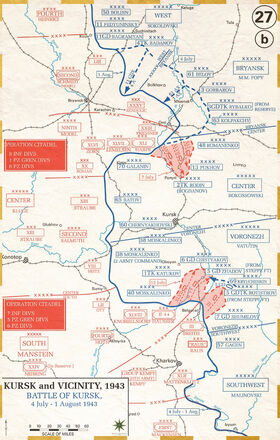

On the eastern front, the indomitable spirit shown by the Russians at Stalingrad was also true of Stalin, who proved himself an almost admirable leader in a national crisis. The Communist slogans of the past were put aside, with the class struggle replaced by the Great Patriotic War. And practical achievements matched the propaganda. With heavy industries relocated during 1942 to the remote regions of eastern Russia, the following year 20,000 tanks and 35,000 planes of excellent quality rolled out from these factories. After the Battle of Stalingrad, the Soviets and Germans took more than four months to regroup. On 5 July, determined to regain the initiative, Hitler launched a massive offensive at a bulge in the Soviet lines near the city of Kursk. The Battle of Kursk was the largest tank battle in history, into which Hitler threw almost 3,000 tanks. However, the German columns got bogged-down in the deep minefields that the Soviets had laid, allowing the Red Army to be safely withdrawn to deep defensive belts. The pincer offensive failed to even get close to meeting, and on 12 July the Soviets launched a counter-offensive where nearly 2,000 tanks clashed at once. By 14 July, Germany was in retreat, with the Soviets pursuing them close behind. Hitler had concentrated all efforts on this offensive without regard to the risk to maintaining any subsequent defence of his long front. The tide had turned and from this point forward, the Soviets had the initiative. During the late summer and autumn of 1943, the Soviets advanced steadily, achieving a series of victories as they pushed the Germans westward across the Ukraine. The Germans were planning the construction of a massive defensive wall called the Panther Line all the way from the Gulf of Finland in the north to the Sea of Azov in the south, but the Soviets advanced too quickly for the construction site to be held. Stalin’s forces retook the city of Smolensk in September and Kiev a month later. The German army in the south was now in full-scale retreat and would be expelled from Soviet territory entirely early in 1944.

In northern Russia the city of Leningrad was still starving under the brutally long German siege that had begun all the way back in September 1941. Although the situation for those trapped in the city was grim, with numerous reports of cannibalism, the Russians were able to get some food and medical supplies via a sliver of land that allowed access to nearby Lake Ladoga. More than 600,000 Russians died from starvation, exposure, or disease during the 900-day siege. In early January, the German forces were finally driven out of the Leningrad region entirely. With the Leningrad siege broken, all German forces on Soviet territory were in active retreat during early 1944. The retreat saw the Germans stepped up their murder campaigns to a frenzy, executing any remaining Soviet prisoners, along with anyone even remotely suspected of partisan involvement. Meanwhile in March, Russian armies reach the borders of Poland and Romania. By the end of May the Crimea too was back in Russian hands, and all of Russia had been liberated.

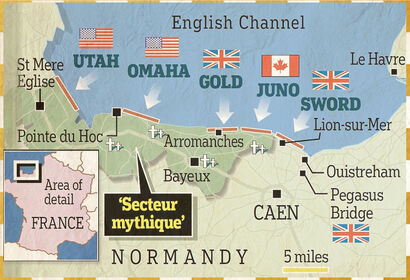

Meanwhile on the western front, the D-Day Landing was fixed for 6 June 1944 under the leadership of Dwight D. Eisenhower. On the first day of the operation the first wave of over 6,000 ships carrying about 130,000 troops roughly half American, and half British and Canadian assembled to the southeast of the Isle of Wight. From there they moved south to five separate beaches in Normandy between Cherbourg and Caen. Another 20,000 airborne troops were dropped by parachute and glider a short distance inland to do as much damage as possible to the German coastal defences. A mass Allied disinformation campaign had meanwhile convinced the German high command that the invasion was imminent at Calais. Yet the first day of the invasion saw heavy casualties for the Allies, especially at Omaha Beach, but they accomplished their objective of fully securing the landing areas. Over the coming weeks, more than 2 million more soldiers would enter France via the Normandy beaches; to this day the largest amphibious invasion in history. The ports of Cherbourg and Caen which framed the area proved more difficult. Montgomery, in command of the British sector, expected to take Caen on the first day, but he was in for disappointment. Stubborn defence and a German panzer division denied it to Montgomery for a month. Further west along the coast Cherbourg resists the Americans, under Patton, for two weeks. The Allies were unable to advance inland in significant numbers until 28 July 1944, but by mid-August most of north-western France was under their control and from there the liberation of France moved rapidly. The German defence, though extremely effective with soldiers often fighting to the last man, was handicapped by a desperate lack of troops in the region, compared to the Allied forces being landed every day. Once again, as at Stalingrad, Hitler ordered that no German forces were to withdraw, meaning the chance to fall back to a strong defensive position was lost. Hitler also had an unwelcome distraction at this time of crisis. On 20 July, the Stauffenberg Plot nearly succeeded in killing Hitler; the most famous of sixteen attempts to assassinate him. More than 5000 people were executed for links with this attempted insurrection, among them Germany's most celebrated general, Erwin Rommel, now commanding the Panzer forces in the west. The conspirators' papers reveal that Rommel was sympathetic with their aims, and he was arrested and allowed to commit suicide using cyanide to prevent a scandal. Patton and the Americans reach Orléans on 17 August, and a week later a French division was placed in the vanguard to enter and liberate Paris. On 3 September the British entered Brussels, and a day later were in Antwerp. Meanwhile Patton's armies had crossed the Meuse at Verdun, towards the Moselle, near Metz. The first Allied soldier crossed into Germany on 10 September, albeit only on a brief mission.

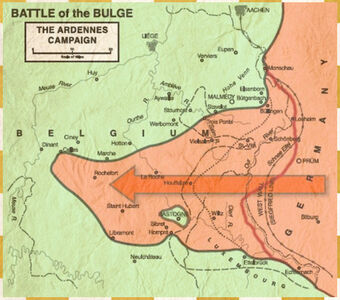

With the obvious possibility of Patton breakthrough the Siegfried Line in the south into Germany’s industrial heartland of Saarland, Eisenhower could no longer devote a preponderance of supplies to the British in Belgium. Montgomery nevertheless attempted a thrust to cross the River Rhine at Arnhem into the Netherlands. Paratroops were dropped on the other side to seize the northern end of the Arnhem Bridge. They succeeded in doing so, but the main army were checked and failed to reach the southern end in time. Thus some 7500 paratroops were left isolated and taken prisoner. The disaster at Arnhem prompted the Allied advance to be paused, in part due to the growing disagreements between Montgomery and Patton, urging different strategies and incompatible demands on Eisenhower in overall command. Thus the Allies’ amazing advance of 350 miles in a few weeks was brought to a halt. A general Allied offensive launched in mid-November all along a 600-mile western front brought disappointingly small results at heavy cost. In mid-December, the Germans, after frantic searches for reinforcements, were able to astonish the Allies by mounting a counter-offensive against through the wooded region of the Ardennes; the Battle of the Bulge. Their intention was to break through to the port of Antwerp, thus dividing the British army to the north from the Americans in the south. The element of surprise and a heavy snowstorm enabled three German armies to push west almost as far as the Meuse. However, the speed with which Montgomery took charge of the northern flank and an outflanked US detachments who managed to hold Bastogne, contained the Germans bridgehead. The Germans managed to carry out a skilful withdrawal that took them out of harm’s way. It turned out to be the last German offensive of the war, and exhausted the resources of Germany on the western front.

On the eastern front, in late June 1944 the Soviets launched a major offensive codenamed Operation Bagration with nearly 2 million troops and thousands of tanks. Within less than a month the route was clear to Warsaw. As they advanced through Poland, on 24 July 1944 Soviet soldiers captured the Majdanek extermination camp before its German operators could destroy the first absolute proof of the atrocities that had taken place there; hundreds of dead bodies, along with gas chambers, and thousands of living emaciated prisoners. As the Red Army made its way deeper into Poland, Stalin’s intentions became clearer; the Soviets “liberating” Polish territory actually arresting members of the Polish insurgency in large numbers.

Victory in Europe[]

The "Big Three" at the Yalta Conference, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin.

By the winter of 1944, Germany was surrounded as its enemies threatened to invade from east, west, and south. On 18 October, Hitler ordered the conscription of all healthy German men aged sixteen to sixty in order to defend the country to the last man. Yet with supplies dwindling the once-mighty Luftwaffe had some of the best military aircraft in the world but lacked fuel to fly them. Even Adolf Hitler himself had become dangerously addicted to a variety of drugs and placed his last hope on the latest German innovations; the V2 the world’s first ballistic missile, and work on developing an atomic bomb. On 4 February 1945, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin came together for a now famous meeting at Yalta, a resort on the Black Sea. Their focus was no longer on how to conduct the war, but on what to do when it was over. Each leader had a different and in many ways incompatible agenda. Roosevelt wanted to ensure that Stalin declared war on Japan as soon as the European conflict was over. Stalin was more interested in extending Russia's borders to those of the old empire before the humiliating provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, absorbing eastern Poland and the Baltic states. Churchill had a greater interest in standing up to Stalin, but was militarily the weakest of the three. Compromises were reached such as the holding of democratic elections in Poland, but all three leaders at Yalta must certainly have been aware that these were empty.

Dresden after the bombing raid

On 14 February, there occurred one of the most controversial Allied actions of World War II. To prevent Hitler moving divisions eastwards to halt the relentless Russian advance, nearly 1250 British and American bombers struck Dresden, a city famous for the beauty of its buildings and full of refugees fleeing from the Russians. Their targets were the railway yards but the result was a firestorm that destroyed eleven square miles of the city. The modern consensus is that around 35,000 peope were killed, predominantly civilian, about the same as during the entire eight months of the Blitz. This calamitous event probably did nothing to hasten the end of the war, for the end was now clearly in sight for Hitler's thousand-year Reich.

During the spring of 1945 the collapse of Germany came with surprising speed. German commanders in the field began to disregard the stream of hysterical instructions from Hitler to stand firm whatever the cost. With Hitler's final reserves sent to the eastern front, the Allies met little resistance when they crossed the Rhine in the north and the south on 22-24 March. On their way east they discovered for themselves the horrors of the Nazi regime in Buchenwald and Belsen; these were not even the death camps, merely slave labour camps subjected to little food and Nazi indifference. In April the noose tightened. The Russians entered Vienna on 6 April. Three weeks later on 25 April they encircled Berlin, and on the same day in a hugely symbolic meeting a small group of American and Soviet soldiers met at the German village of Stehla. On 29 April, the German army in Italy surrendered to the Allies.

Russian soldiers raise a Soviet flag over the Reichstag in Berlin in May 1945 marking the defeat of Germany.

In the early hours of 30 April, in the elaborate bunker beneath the Chancellery, Adolf Hitler put his affairs in order. He appointed Admiral Dönitz and Joseph Goebbels as his successors, dictated his last will and testament in which the Jews were still blamed for the war, and married his mistress Eva Braun. With the Russians only two blocks away in the streets above, Hitler and Eva Braun retired to their quarters and committed suicide; she took poison, he shoots himself in the mouth. Their bodies were hurriedly cremated in the garden. The following day Goebbels completed his sole official act as Chancellor, informing German high command of Hitler’s death and requesting a ceasefire. He then ordered SS men to give his six children lethal injections and shot his wife and himself. Hitler had been appalled at his nation surrendered in World War I without a single foreign soldier setting foot on German soil. The same day he died, a Soviet flag was hanging from the top of the Reichstag. A week later on 7 May, the unconditional surrender of all the German forces was signed, which went into effect the next day; 8 May 1945, V-E Day, Victory in Europe.

Victory over Japan[]

The US victory at Midway in June 1942 was the turning point in the war for the Pacific. From then on, Japan’s struggle turned to maintaining the vast swathe of South-east Asia, captured in the months after Pearl Harbor, in the face of relentless American pressure. This encompassed the numerous islands including the Philippines, the Marianas, Borneo, Indonesia, and half of New Guinea, as well as on the mainland including much of the coast of China, and from Vietnam to Burma to Singapore. In many respects, the whirlwind Japanese campaign had been too successful, with too many fronts to defend.

The first strategic objective for the Allies was to secure supply lines between the US and Australia. On 7 August, the Allies launched an amphibious offensive on Guadalcanal, to the northeast of Australia, landing more than 16,000 US Marines. Attrition and limited supplies eventually resulted in unsustainable losses for the Japanese, who were forced to abandon the island in February 1943. A pattern had been set of painful Allied progress through the islands towards Japan, with every step bitterly and bravely contested by the Japanese, to the last man in virtually every engagement. A significant step in the slow move north was the US assault on the Japanese naval and air base at Truk in the Caroline Islands in February 1944. Eleven Japanese warships and more than 300 planes were destroyed here, in the first radar-guided night attack. The next crucial step was the Marianas, a group of islands from which US planes would be within bombing range of Japan herself. In June 1944, American marines landed on the island of Saipan, and after three weeks of fierce fighting, against 30,000 securely dug-in Japanese defenders, the two Japanese commanders commit suicide. At the same time, in the two-day Battle of the Philippine Sea to the west of the Marianas, the Japanese have lost 400 planes and three aircraft carriers. With the capture of Saipan, soon followed by the other Marianas, by November 1944 the first B-29 bombers took off on the long trip to bomb Tokyo.

Ensign Kiyoshi Ogawa, who flew his aircraft into USS Bunker Hill during a kamikaze mission on 11 May 1945

With the process of battering the Japanese people into submission now under way, American attention turned to the Philippines. It was a campaign close to the heart of the US commander Douglas MacArthur, for it was he who had relinquished them to the Japanese in 1942, after a heroic struggle. The first US landing was on Leyte in October 1944, and within days, sea and air battles were raging in the area including the first Kamikaze attack; named for the "divine wind" that dispersed the Mongolian invasion fleets of Kublai Khan in 1274. Leyte was not secured until Christmas Day. Manila, the capital of the Philippines, withstood a four-week siege before MacArthur secured it in March 1945. While the Allies made gradual progress island-hopping towards Japan, the confrontation between the two sides on the mainland was occurring in Burma. During 1943, the only Allied activity was guerrilla warfare behind the Japanese lines, carried out by a combined force of British, Gurkha and Burmese troops under the command of Orde Wingate. Their sabotage of bridges and railway lines proved crucial when the Allies at last sent a conventional army under William Slim east from India. The Battle of Imphal and Kohima (March-June 1944) was Slim’s first success, but the downpour of the monsoon and the jungle conditions made progress slow. It was not until March 1945 that he took Mandalay and moved south to seize Rangoon, essentially completing the recovery of Burma just before the arrival of the next monsoon.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, by Joe Rosenthal / the Associated Press

The second summit of the three western leaders took place in July and August 1945, at Potsdam near Berlin in occupied Germany. It involved two changes of cast since the gathering at Yalta: the US president was now Harry S. Truman, following the death three months earlier of Roosevelt, and the British prime minister was Clement Attlee after the collapse of the wartime British coalition government. The main topic was the continuing war against Japan, and Stalin was now let in on an important secret; that the US had had successfully tested an Atom Bomb in the New Mexican desert on 16 July. Scientists had theorised such a weapon for years, and active research on its development had been taking place not only in the US but also in Nazi Germany, Japan, and the USSR. The American effort, which was conducted with substantial help from Canada and Britain, was code-named the Manhattan Project. On 26 July, a Declaration was sent to the Japanese from Potsdam demanding an unconditional surrender. The final stage in the US advance towards Japan had begun in February 1945. The distance of the B-29 bombing raids on Japan would be halved if the small island of Iwo Jima could be captured. The island's obvious strategic importance meant that it was defended by 20,000 heavily armed Japanese troops in a network of underground tunnels and bunkers. US marines met fierce resistance when they landed in February, and surrounded the daunting Japanese base of Mt. Suribachi. After a brutal four-day struggle, US forces reached the peak of Mt. Suribachi on 23 February, where an Associated Press photographer took a now world-famous photograph of a group of Marines raising the American flag. It would be more than a month, with every yard of the US advance hotly contested and more than 20,000 men were dead or injured on each side, before the island was finally in US hands. By now, the desperate suicide attacks of the Kamikaze pilots had become a familiar danger, with an apparently unlimited supply of Japanese pilots willing to sacrifice their lives. With Iwo Jima secure, attention turned to the nearby island of Okinawa, about 300 miles from Japan; the last large-scale battle in the Pacific, and the most intense. US forces began amphibious landings on 1 April 1945, where more than 100,000 Japanese soldiers lay in wait. Five days later, no fewer than 355 kamikaze planes were launched against the large fleet of naval vessels anchored offshore. Yet the fleet was able to remain in place and continue to offer air support, and Okinawa in US hands by the end of June.

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima

Japanese defence of such courage and ferocity at every stage, and the mounting Allied casualties, made it more attractive to contemplate bombing Japan into submission. Napalm was first used in a raid on Tokyo on 9 March 1945, where the timber buildings caused a firestorm killing some 80,000 people and making another million homeless. In the next few weeks there were similar raids on all the major cities of Japan, but as with the Blitz on Britain and Germany, there was no sign that these horrors increased the likelihood of a Japanese surrender. No response had been received to the Declaration from Potsdam demanding unconditional surrender; it has since been discovered that Emperor Hirohito pressed the case for surrender but failed to persuade his generals. President Truman now deemed it necessary to use an even more terrifying new US weapon. On 6 August 1945, a specially adapted B-29 took-off from the Marianas with the Atom Bomb on board. It exploded over Hiroshima at 8.15 a.m. demolishing four square miles of the central city and instantly killing to about 80,000 people; many more tens-of-thousands would die later from the effects of radiation. When this did not bring an immediate surrender, three days later a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. On 15 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s capitulation in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration. The use of the Atom Bombs has remained the subject of intense controversy. Would Japan have surrendered if the force of the weapon had been demonstrated on a deserted island? Was Japan already on the verge of surrender to conventional warfare? Did the United States wish to demonstrate its newfound power to the Soviet Union, as much as to the Japanese?

Aftermath[]

The famous imade of a sailor kissing a nurse as Manhattan's Times Square celebrates the surrender of Japan on 14 August 1945.